Zine : read

Lien original : It’s Going Down

En français :

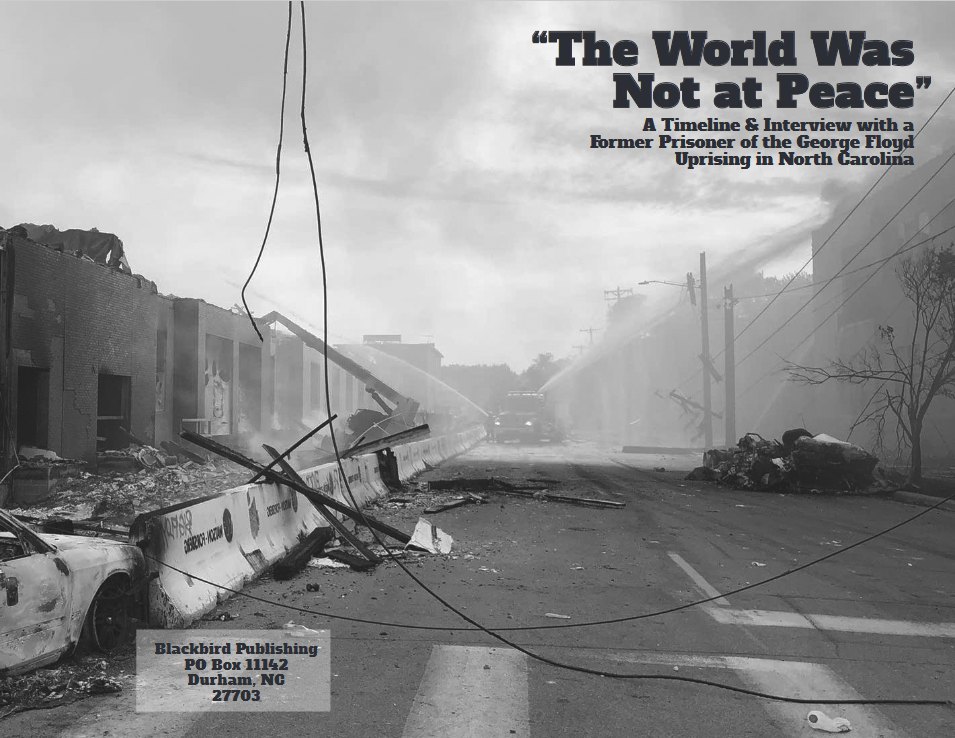

An interview with a former prisoner of the George Floyd uprising and a timeline of the rebellion in so-called North Carolina.

Download and Print PDF HERE

This is an interview with Shawn Sutton, a longtime resident of eastern NC, musician, and participant in and prisoner of the 2020 uprising. John was also a participant in the rebellion, is a longtime NC resident, and has been involved in anti-prison organizing and prisoner support for around 15 years. He met Shawn through correspondence while she was at NCCIW in Raleigh. Shawn got out in February 2022, and the interview was conducted by phone in June 2022. If you’re able, please help Shawn with her reentry by CashApp at $SeckundChanse1. You can also check out some of her music at ReverbNation.com/SeckundChanse.

John: Thanks a lot for talking with me, Shawn! I guess maybe we could start things off, if you want to just have a second to say a little bit about yourself, just a little brief introduction.

Shawn: My name is Shante Sutton of course, legally. They call me Shawn. I’m from Greenville, North Carolina. I was born there. I’m 36 years old.

John: Did you grow up in Greenville, like your whole life?

Shawn: Well, no, not exactly. I grew up in Bertie County, North Carolina. That’s where I went to elementary, middle school, and high school. I’ll have to say that I grew up there, but I was born in Greenville and moved there when I was in 5th grade. So I was about 10 or 11 when I moved there, very early in my life.

John: Cool. So, can you maybe talk a little bit about just what brought you out in the streets in late May 2020. And how you heard about things going on? What led up to that?

Shawn: Yeah, well, in the beginning, the world was in an uproar. Basically, not just my city, not just Greenville, but worldwide, because of the George Floyd incident. You know? Him getting killed by the police officers… The world was not at peace.

I wasn’t trying to be a part of that, honestly, because of my legal situation and everything I had going on in my own personal life. I wasn’t really trying to be in the middle of anything against the police. But then shortly after that, someone that I knew personally was gunned down by the police in Tallahassee 1. That was someone that I knew, that I did prison time with, and just someone who we related to each other in more ways than one. So when I got the call, when I got the call that he had been shot by the police, that kind of changed my entire perspective on everything that the world was upset about. This to me became personal. So yeah, that pretty much explains why I decided to go out into the street. I was with the mindset basically, not so much as trying to do anything specific, you know. It was just anger and emotion.

So, that’s sort of my reasoning for that. Just, making noise and being a voice for him. That’s pretty much my reason behind that.

John: Yeah. In a fundraiser that was organized for you, you were talking a lot about doing time with Tony McDade. I was just curious, it seemed like with all the media and attention, especially because of the video, and then the riots in Minneapolis, a lot of what happened to Tony McDade got lost in the chaos and kind of lost the attention.

Shawn: Yeah, and not even that. It was more so that they felt like he was a criminal, for one. Like he was armed and dangerous, for two. They felt like the incidents that led up to that, basically everything masked the fact that he had been shot down in the middle of the street in front of people by police officers. That no longer became the issue. The issue was, “Oh, his record,” and “he did this much time for this,” and “Oh, he had mental issues.” It never became “Oh, well, he got killed by police officers.” That was never a factor. Do you understand what I’m saying?

Just like my situation is, to me, like, “Oh, well, she already has a record,” and “oh, she’s already had run-ins with the law,” never mind the fact that this happened or that happened. That doesn’t matter. “Oh, well, she has a record.”

John: Yeah, that seems like a pattern that’s happened a lot of times before when police murder a Black person. It seems like a lot of times the media does that, but even the movement does that too…. At least the liberal parts of the movement are like, “Well, oh, but they had a gun or they had a knife or they had a record.” So people don’t go as hard for that person as they would for somebody who they think they can portray as innocent. It’s all about like optics and bullshit.

Shawn: Yeah, most def, but you never really know. It’s never, “Oh, well, the police murdered this person.” They never use that title, ‘murder,’ when assessing police officers. It’s never, “Oh, they murdered someone.” No, that’s never the word that you hear in the beginning. You know what we have to go through to even shine the light, what it is that we have to do to even acknowledge it.

John: Yeah. Thanks for keeping the focus on Tony McDade like that. Like, for real. I also want to ask a little bit about Greenville, if that’s cool. Just because there’s a lot of, nationally in the media and the mainstream press, but even in like movement circles and people writing about their experiences in the uprising, there’s a lot of talk about big cities like Minneapolis, Atlanta and New York, Oakland. But there’s less about smaller towns like Greenville, like High Point, like Fayetteville, even like Durham, actually. But the uprising spread to these towns too.

Shawn: Even smaller than that, when we talk about… like I said, I grew up in Bertie County, and not long ago, two years ago when the guy was shot down in his car by the police that were doing a search and investigation and he was trying to back out and they said he was using the car as a weapon. This is a small town that they brush that type of stuff under the rug. No one in that town is making noise the way that those big cities, like Chicago, or California, or New York do. With their population so many people that are willing to just step out and be a voice. You know?

But in towns where people been there their whole life, they’re comfortable, they don’t want to mess up what they’ve got going on. That’s just what it really boils down to a lot of times. It has been going on for years and years before me, before you, you know? After a while, people become complacent, become comfortable in there, it all stems from fear. People are just happy that they have a place to live, they have food, they don’t want to go to war with the police. It’s more, “I have to work here,” or, “I have to live here,” or, “I have to shop here.” But in bigger cities, they don’t care about that shit.

John: Yeah. And people in smaller cities, it’s like everybody knows everybody. It’s like, “Well, if my boss sees my picture in the paper at the riot, or the cop knows my name and they know what school my kid goes to.”

Shawn: Exactly.

John: Part of why I wanted to ask you about Greenville, is just because in 2020, summer 2020, one of the amazing things was that the uprising did spread to smaller towns. Right? It didn’t just stay in Minneapolis. In North Carolina, Charlotte went crazy May 29, then things picked up in Raleigh and Greensboro the next day, and then it spread to Fayetteville and Greenville and High Point and kept going on in Raleigh as well on May 31.

As things were spreading to smaller towns, I was just curious, insofar as you feel comfortable talking about it, obviously, what was your feeling about Greenville? What did it feel like when the uprising spread to Greenville? What made things boil over or what were the tensions going on there in like that specific city?

Shawn: Honestly, you know what? To be honest, the uprising was going on in my city two days before I even got involved. There were already peace rallies going on that people were attending in large numbers. But every day I was going to work. Every day I was waking up in the morning and going to work reading about what was going on on social media, or hearing about it on local news, or conversations. But I was at work every day and every night, I was coming home and the city was dark, we were on a curfew at the time. So, there was really no involvement on my part.

But like I said, then I received a call. Not only did I receive a call, I received a link to a video that was my… you know… a good friend of mine. And at that time of the video, he was dead already. Laying on the ground already. My emotions in that moment were just like, and even still, “I can’t get involved.” I actually was with fellow friends and people that all knew him from federal prison, and basically we were coming together. We did a memorial service for him. During all of this, the uprising was going on and we’re still emotionally trying to wrap our heads around it. It’s not just something we see on the news now, it’s someone that we know personally. So we’re all just like lost at that moment. It’s just like, “What? How did this happen?” We hear about this type of stuff on the news, but to actually experience it is kind of just mind-boggling.

We were all just grieving. But during all this, I hadn’t got to that point yet. It still was painful for me. We were really focused on him. We set up a GoFundMe, you know, we were just thinking about that. And then all of a sudden it just hit me. I came home from work one day, one night, actually, that’s all everyone’s talking about, how all the stores are closing down, and everyone was gonna be downtown. And now it’s no longer peaceful. It’s not peaceful now. We’re just now catching the flame of what the world has already encountered. The flame has just now hit us. Now this is all the world is talking about and it’s in my little city now. It was at that moment where I was like, “You know what? Now I feel like I have a reason.”

It didn’t have nothing to do with me, because, believe me, I’ve already been through my own war with the local police department. I’ve been through my own war with the judicial system myself. I could have been had a reason to say, “I’m going out here, and this is what I’m gonna do, and this is what I’m gonna say.” But at that moment, it didn’t hit me for me for me. You know? It was for a whole nother person. And it was like, “This person is no longer here, and somebody has to be a voice for this person, someone has to let out the anger for the person. Someone has to put a light on this person.” You know? That’s where my mind was at that moment. It didn’t go no further than that.

John: That’s really, really fucking powerful. Thank you for sharing that.

Okay, so this is not a question I had written down. But I hear a lot of people talking about this. Adrienne Marie Marie Brown even wrote a book, a fiction book recently, that I’ve been reading, it’s like this beautiful fantasy book about Detroit. It’s called ‘Grievers.’ I feel like a lot of people have talked about the pandemic in the context of grieving and grief. But also, obviously, all of the police murder and violence in 2020 and uprising against it, also in the context of grief. Hearing you talk about it…Coming out in the street was part of your own personal war and your own struggles against the police department and the State and all that, but also it was a part of grieving for Tony, right, and I’m just curious, a lot of times it seems like there’s a part of the movement or whatever liberal aspects of it that don’t want people to be angry or don’t want people to be wild in the streets, and they want to shut that part of grief off.

Shawn: Exactly. They want us to react to it as if it’s normal. As if it’s something we should accept. Like we shouldn’t have no emotional concern on the matter.

John: Yeah, and it seems like that locks people in this state of suspended grief. You know what I’m saying? If you’re not gonna let me be angry and attack what’s literally trying to kill me, then I can never move through my grief.

Shawn: Right. You don’t know how many people I encountered during my incarceration, whether it was in the county waiting to go to court to hear the outcome or whether it was when I got to prison, and I was serving my sentence. So many people said to me, not inmates, really, it was more so the officials, “Oh, well, why would you go out there? Why would you participate in that? And what if you would have got injured? And did you know this person personally?”

All those questions came to me from different individuals and that just lets me know that the world literally has—not the world, but a great number of people in the world—have shut themselves off emotionally to things that does not affect them personally at their front door. Do you understand what I’m saying? They don’t have the emotional capacity to even hold on to something so far away from their own front door. So it doesn’t matter to them. They cannot even grasp the concept of another individual reacting to something on such a high standard because it did not have anything personally to do with them.

John: Yeah, I mean, it’s not surprising, but to be shamed by people for doing something that is an act of integrity and is inspired by your love for somebody who was taken from you by an enemy, you know, it’s like…

Shawn: Yeah, but by the same token I had people would come to me [in prison] and say, “Oh, I heard you were here for this,” and, “Oh, man, that was brave for you to do that,” or, “If I was there, man, I would of…” You know it goes both ways.

John: I’m sure there are people in NCCIW who were into it.

Shawn: Yeah most definitely.

John: We were just already talking about this, so this may be repetitive, but even on some of your Facebook live stuff, I was watching it when you sent me the videos. And I was like, “Whoa!” For being on break from work, I just want to say you’re very articulate considering you’re on break from work when you were filming that shit. Like, if you have me on lunch break I would not be able to give the speech that you gave.

Shawn: But if you notice in the video… not to cut you off, but my phone kept ringing! [laughter] The other person that was like, “Yo! When is my break coming!”

John: You were like, “Shut the hell up. I get I get a long break today. I got some stuff to say”. [laughter] But watching that kind of made me think.

A lot of people have talked about this very articulately, but I just want to just hear your thoughts. One of the things also about this uprising wasn’t just that it spread everywhere, but also, it was uncompromising. It was like, we’re not ‘speaking truth to power,’ this is not a protest, we are trying to actually exact costs, financial material costs on this system that is like killing us, or killing our friends, killing our people. And so there’s a strategy there, there’s an intelligence there.

So I’m just curious how you would say in your own words, that need for crossing the boundary into actually organizing conflictually, being forceful, being militant, however you phrase it?

Shawn: That question is perfect because before the video that we’re discussing, that you watched on Facebook Live, where I was discussing why, or how we felt, I just had got off the phone with my mother. I was actually talking to my mother on the phone when I pulled up to work that morning. It was the morning after the uprising, what I participated in, literally the morning after. It was all so mind boggling, the way that it all transpired, chronologically. The uprising. Conversation with my mother. Video. Literally, literally, within a 24 hour time period, all that transpired. So the conversation with my mother was more so her saying, you know, “Shante baby, please, take the videos off.” Basically, from the uprising, we went live as well. During certain parts we were live and lot of people were like, “Oh, God, take the video off. They were so worried about what if the police see the video link? So, “Take the video off!”

She was like, “What about this or that, you know, y’all could be peaceful.” And I remember saying to my mother, “Mom. Peaceful about what?” You know. I have the upmost respect for my mother, don’t get me wrong. I do. I love her. I do at least listen to her opinions, but my mother would tell you I’m my own person. I have my own mind. I’ve always made my own decisions. You know, no matter what nobody is saying about them. No matter what nobody thought about it. No matter even as a kid, if I was going to get my ass whooped about it. I did what I wanted to do. No matter what nobody else is doing. Everybody else in the world could be wearing Jordans, and I’ll be walking around in flip flops. I’ve just always been me. So when my mother called me, “I’m like, Mom, I love you. I do. But I’m not taking the video down.” I’ll put the video on private where only my friends could see it, because she was so worried about what people were saying and it was almost going viral and everybody was watching. And I’m like, well, Mom, what will me taking the video off at this point, all these people already seen it, what will me taking it off accomplish? And not only that, what are we coming peaceful about? These people already know what it is that we’re feeling. They already know what it is going on. Because it’s not only going on in our world, it’s going on in their world too. We all live in the same world.

So this is not something that they’re not aware of. It’s not something that we haven’t already spoken on many of times before. People before had been speaking, and marching, and protesting, on these same matters. Right? So this is not something that’s new that we bringing to these people. So to me, it was like, “I hear you but don’t agree. And what I’m doing, and what I’m saying is what I do agree with.” I agree that there comes a time when we have to fight fire with fire. I agree with that. I agree with sometimes people have to be a voice for other people, because some people are not here. I agree with that.

I know that if Tony McDade was here and something happened, because there were a lot of people but I’m speaking on him because this is someone that I know personally, this is why I’m making this about him, but it goes for everybody. I know that every family member in each victim’s case says the same thing. Like there’s somebody in every case that says, “Listen, I had to be a voice for this person. Or I had to do this because of this.” That’s why.

And they don’t want you to do that. They don’t want you to come out here and try to come together and be a voice and be an army, be soldiers. They don’t want you to do that. That’s why there are laws and stipulations that are put in place to prevent certain things like this from happening. Because they don’t want you to come out here and make noise and shine light on the injustice that’s going on right here contained in our system. They’re making it seem like it’s ok, like it’s right. They’re painting the picture as this is right. People have become oblivious to the fact that we have rights as well. But we’re so accustomed to being on the end of the law, it starts to seem null and void. “Oh, well, maybe we don’t have rights,” or, “maybe we can’t speak out or maybe that’s not what we’re supposed to do. Because they’re gonna lock our ass up or they’re gonna kill us.” To me, that just seems like a lose lose.

John: Yeah, for sure. And there’s also just that collective trauma of movements that have been crushed and leaders put in prison and everything else. And so, I think sometimes people scream “Peace! Peace!” and they mean well, but they’re just traumatized from repression. But then other times other forces are just like trying to be the counterrevolution, just trying to keep you from fighting back, period.

Shawn: Yeah, yeah. Yeah.

John: So I got just a couple more questions if that’s cool. You good on time?

Shawn: Oh, I’m good.

John: Word. So, there’s been a wave of rebellions in different cities when cops murder somebody in the last 10 years, since Oscar Grant was killed, since Ferguson, etc. This has been going on hundreds of years obviously, but in the last like 10 years, a lot of times it’s almost all Black folks in the streets taking charge and especially leading the more forceful conflictual stuff. But this time—and a lot of people have talked about this, right—so like, Black folks were in the lead, but there were a lot of Latinx folks, a lot of white folks, a lot of indigenous folks in some towns also joining the fight and being uncompromising. And that’s not totally new, but it was like a little new for some people. And I’m curious if that was true in Greenville or not, or just what your thoughts are on that?

Shawn: It was definitely very diverse in my city. Very, very diverse. I mean, honestly you know what? I think that just comes from the fact that not only has this been happening in the Black community but it’s been happening in the community. Racism period has just been happening in the community, and we’re not just talking about race as in skin color, I’m talking about sexuality, or religion, or all those things. So it might not have just been affecting my community, it has been affecting everyone’s community. So you have interracial relationships, you know, all that. So to me, I even was in the county with someone of another race that was going through the same situation that I was going through, and that was just like crazy. To see other ethnicities saying, “oh, yeah, this is a black lives movement.” You know, it lets you know that this is just hitting home for everyone. It’s not just a race thing. It’s not just about race. When you start seeing the diversity at such high levels then you know this is more than just race.

John: What you said about interracial relationships too made me think of the Wendy’s getting burned down in Atlanta when Rayshard Brooks was shot, right? Because his girlfriend was white, right? And she gets on camera, allegedly, without a mask as participating and burning down the Wendy’s [where Rayshard was murdered by police] with a crowd. Then all these liberals on Twitter who were not even there were like, “this woman is a white outside agitator. She should be arrested.” Then it turns out it’s his girlfriend and she’s doing time because these ‘do-gooder’ liberals called the cops on her. You know? She had a reason to be there. It’s absolutely crazy. Even if she wasn’t his girlfriend, it’s still like what she allegedly did was righteous. But yeah it’s just crazy.

Shawn: We’re never going to understand that.

John: Yeah that was some absolutely disgusting shit.

Shawn: Yeah, makes me not even want to come outside man.

John: I know, it’s tough stuff. I try and balance out the really depressing stories like that one, with the positive stuff, like people actually helping each other out and keeping each other safe, but damn.

So that leads to just a couple more questions. I wanted to also ask about afterwards, right? So like 1000s of people were arrested. A lot of people were arrested all around the country. A lot of them were felonies, some of them are for misdemeanors. You ended up facing some felony charges for what went down in Greenville and you got about 10 months inside NCCIW [NC Correctional Institution for Women].

I’m curious, since you have that perspective, what do you think the movement on the outside needs to be doing to better support prisoners of the uprising? Or just more things that we could be doing to support people who got time?

Shawn: Honestly, I think people are being kind of lost to the fact that people were actually arrested for the things that went on during the George Floyd Uprising. I think that people are still kind of lost to that, I don’t even think that people know that there are people still serving time. I mean, even in my case, I’m still shocked myself. No one thought in my situation that, “Oh, well, she’s going to go to prison, or be arrested literally within 24 hours. You know. Years could go by and I’m still trying to figure out well, “why did…. What?” You know?

Like, I can tell myself, oh, well, in my city I have a history. I have a background. They know me. And I just feel like I was a perfect candidate.

John: For arrest? Like for them to target you?

Shawn: Oh yeah, most definitely. They’re doing their investigation and there’s 1000s of people that they can not identify, and BOOM, here comes the license plate that goes across their screen. And that license plate leads to a name of someone that they are very, very familiar with. “Oh, well, they already have a record. Oh, well, it won’t be nothing for us to pin this on her. Alright we are going to get her.”

For people that are still incarcerated, I know how I felt when I heard from people [on the outside]. It was a breath of fresh air because the whole entire time you’re thinking, “I think it’s for a cause.” Right? It’s for a reason. Whether it’s what they said I did or not. What I did do, I did it for a reason. So to know that it was heard or seen by someone and it impacted them in whatever way. You know that something was accomplished. That’s all that matters.

I can guarantee you, no one that’s sitting in prison, for what they’re sitting in prison for as far as the uprising, is feeling sorry for themselves. No one that’s in prison for that is feeling sorry for themselves saying, “Damn, I wish I hadn’t done that.” No. I doubt they would put their life on the line, and now they’re saying, “Aw man, I shouldn’t have done that.” No, no, no, no. Everyone who participated in the George Floyd uprising, for whatever reason, whatever their thoughts were on the matter, whatever their emotional connection was on the matter, is basically just wanting to know that it impacted someone. Whether it just impacted them to know that they had the strength, or the mindspace to say, “F- this. I’m going to make a plan and I’m going to do whatever it is that I gotta do to put attention on this matter.”

Honestly, I mean, I doubt if anyone is feeling sorry. We get the time and you know, we probably can’t believe that we’re sitting in prison for it, but when you know the type of judicial system that you fighting against, it no longer becomes a surprise. It’s no longer a surprise anymore. It’s like, “Well, hell. But thank god I’m still alive and at least they didn’t kill me.”

John: That’s really powerful. I appreciate the way you phrase it. I think as soon as you get outside of circles of people who have a lot of direct experience with the judicial system, or who are in touch with prisoners or people in prison anyway, it’s like everybody’s forgot that there are hundreds of political prisoners from this movement. It’s like… there are groups giving them support, raising them commissary funds, writing them letters, but a lot of the broader public, it seems, wanted to believe the uprising was peaceful and therefore there’s no prisoners from it. It’s this crazy act of collective amnesia.

Shawn: I don’t know if they’ve never expected anyone to get arrested for this type of stuff? I think people felt like, “Oh, well hell. The police is killing us, so it shouldn’t be a crime for us to go out here.” No one expected anyone to get arrested for that at that point in time and still be incarcerated. “You mean to tell me they’re still incarcerated?!” You never expected that. We were thinking, “Oh, well yeah, they’re gonna lock the people up. They just want to scare people, but they’re gonna let them out.” But they were really giving people years.

John: Yeah, this dude in Philly, I forget his name, but this dude in Philly just got the longest sentence yet. I think it’s almost 15 years for something. It’s a property crime and it’s not even like an assault or something. It’s crazy. It’s absolutely crazy. I know Philly people are trying to support him 2.

Shawn: And all the restitution!

John: Yeah you have to pay all that money too.

Shawn: I’ll pay the money when some of these people rise from the dead. [laughter]

John: Did you have restitution they say you owe? I didn’t know that. How much restitution?

Shawn: It’s like $7,500.

John: Okay, I actually didn’t know.

Shawn: No problem. They need to know this. Man, like, right? Let me tell you something, those buildings, all of those buildings are insured. You understand? They’ll come in and someone’s broke the glass out of a window, the next day the glass is replaced. They can’t pinpoint and say that I did this or that. But yet you want to give me restitution? What am I paying for?

John: It’s like they can’t even prove it. They just want to keep people in debt forever.

Shawn: Oh yeah. Oh yeah.

John: I got to just one or two more questions if that’s cool. So a lot happened since 2020, it’s 2022 now. Obviously racist and white supremacist violence and organizing has increased a lot in some places. A lot of folks who are still involved in the struggle have retreated away from the streets. There’s a lot less stuff going on in the streets right now in terms of demos and struggle. So just in that context, right now, however you’re reading it, what do you think people should be doing right now to push the struggle forward? Are there any individuals or groups you want to lift up or give a shout out to?

Shawn: For one, before I get into any others, I would personally like to give a shout out to the LGBTQ community for their support.

Honestly, you know, right now with the way everything is in the world. I would only suggest that’s the way the government would want it to be, whether it’s the COVID-19 epidemic, or whether it’s this extreme hot ass weather, whether it’s the low employment rate, whether it’s the high taxes or the high gas prices, or whether it’s the high food prices, or this the high cost of living, period, you will have to only assume that the government has it all set up that way so that no one would want to go out and do a damn thing. For one its too hot. “I don’t want to go out there and be a part of something. Gas is too high. I can’t go out and be a part of nothing. Everything is just too high and my job is only paying me pennies and I got to do this.” Everything just takes their minds off of what was really inspiring us to go out here and come together. And all I can think is this is the way the government wants it.

They don’t want us to get out here, getting a part of nothing. They don’t want to see another uprising. “Oh, it’s too soon. Oh, the economy has lost so much money, Oh my God, all the negative backlash. We can’t have that again right now. Let’s put some things into place to keep these people’s minds off the negative. Let’s get their mind off of trying to get them to come together and fight for something. Let’s keep their mind off that. Let’s raise these damn prices and let’s turn the heat up.”

John: Yeah, it’s gotten crazy. It feels a little like the inverse of 2020, a lot of us were sitting at home not allowed to go to work or there wasn’t a work to go to because it was the pandemic. People were sitting at home with free time and some people had stimulus checks, so people are like, “well, you know, I can afford some gas and some groceries.”

Shawn: Where are those checks now, man!

John: Oh man, that shit’s gone, gone like the wind. But it’s interesting, the way that the open space of the pandemic kind of made space for the uprising in a weird way. You know what I mean?

Shawn: Right. Yeah.

John: The pandemic was horrible, but it’s also like, that was a huge part of the reason people wanted to be together in the streets too. I appreciate you bringing up prices and everything now.

Shawn: Yeah. I think the main thing right now, man, for us and for the people as a whole is to enlighten ourselves and become knowledgeable to not just what’s going on now, but to our history, the uprisings that came before, to understand in a more powerful aspect. Not just where we’re going, but where we came from. You understand what I’m saying? I think knowledge is the power of it all. If we teach ourselves and invest our minds into something on another level, then they won’t be able to just tell us anything, or do us any kind of way, because we would have knowledge and wisdom to fight these battles, to change something even more powerfully, you understand what I’m saying?

Once they take our minds away, they might as well just take our souls because we’re walking around empty, hollow. We can’t stand up to anything being hollow. Knowledge is number one right now, to overcome that fear because when you don’t know things you are fearful. You’re scared. We have to open our minds to this shit man.

John: Yeah I think right now there’s a lot of people just studying, doing group education, trying to study the situation, and trying to study what happened the last couple of years, last 200 years or whatever.

Shawn: Yeah, and for real for real, if you got 5 people to listen to anything you say, keep talking! And five more people are gonna listen. That’s that’s what people do, they follow. So, once you get them to listen, then they can get someone else to listen to them.

John: Okay, I got one more question, if that’s cool with you, Shawn. I’m trying to end on a positive note. Things are rough but I’m trying to end on a positive note.

Shawn: Man, it’s all positive if you’re alive and breathing out here.

John: That’s true. Hah, that’s fair. Okay, so, if we ever win a world without police, and capitalism, and prison, and America, and all that bullshit… what is the first thing you’re going to do?

Shawn: [long sigh] I’m gonna tell you, honestly, I’m a very simple person. People who know me know that. I’m into the simple things in life. So just to know that I can ride around, turn my music up, have my window down, and be free… Not worry about getting pulled over, or not worried about going to see any probation officer, not worried about them trying to figure out where I am. Just enjoying life without the extra stress.

John: Yeah. That’s a beautiful answer.

Shawn: Yeah, that would be it for me.

An Incomplete Timeline of the George Floyd Uprising in North Carolina

The following is a partial timeline of the George Floyd Uprising, as it played out in North Carolina. It is not an analysis or an interpretation of the events, and is certainly not comprehensive: it excludes descriptions, for example, of smaller demonstrations that repeatedly occurred in towns such as Morehead City, Dunn, Newton, Huntersville, New Bern, Goldsboro, Clinton, Chapel Hill, Beaufort, Boone, Rocky Mount, Wilson, Winston Salem, and many others.

This chronology intentionally focuses on the more confrontational activities of the period of late May to September. This is not because legal or less “rowdy” protests necessarily held less meaning for their participants or did not play a role in advancing the struggle forward, or because non-protest activity wasn’t equally important: The hundreds of workshops, assemblies, spiritual gatherings, print-making, murals, memorials, and other communal events absolutely constituted the creative lifeblood of rage, imagination, organization, and healing of this uprising.

Rather, this timeline focuses on these more confrontational actions because they have been at particular risk of erasure by the center-left press and non-profit activists, and therefore merit being specifically collected in one place to be able to appreciate their geographic and political scope.

Beginning as early as the first week of June 2020, and certainly picking up steam after the uprising waned, mainstream press, local politicians, and social media unleashed a tidal wave of collective confusion and misinformation, driven in part by left-leaning conspiracy theories about outside agitators and secret white supremacists, and (later) by Democratic electoral priorities. By October an isolating pandemic winter and presidential election both began to loom large in the collective imagination, and one was reminded of what an insightful author for Black Agenda Report once said after the Ferguson rebellion: “The Democratic Party is where movements go to die.”

In addition to sowing division and paranoia amongst protesters themselves, these narratives threatened to erase or obscure the nature of what happened that summer: A nationwide uprising against the police, absolutely led by Black youth but with unprecedentedly multiracial participation, waged the most massive attack on American state forces and capitalist property since the late 1960’s. In addition to reducing the police’s ability to police in many cities, the uprising’s roughly 23 million participants succeeded in posing a practical question to the country writ large that decades of social movements had failed to even approach: what would it mean to abolish the police, or perhaps the State itself? This uprising opened a new horizon that cannot easily or immediately be closed.

Some statistics are grounding here. In North Carolina, according to a June 8th edition of the Triangle Business Journal, “nearly 1,000 insurance claims came in between May 30 and June 6 from businesses in Raleigh, Greensboro, Greenville and Charlotte. Altogether, they total more than $10 million in damages, according to NCDOI. Figures for damage to state property total $750,000 for that same time period.” Those numbers proved to be a low estimate.

Nationwide, according to the Daily Mail, upwards of $2 billion in property damage occurred in this first week. Shemon Salam and Arturo Castillon point out in the introduction to their book, The Revolutionary Meaning of the George Floyd Uprising:

At least 28 people died in the wave of social unrest that rocked the United States from late May until July in 2020. In this 10-week period, there were 574 riots: 624 arsons; 2,382 incidents of looting; 97 police vehicles were set on fire; and 16,241 people were arrested for protest-related activities. In addition, at least 13 police were shot, 9 were hit by cars, and 2,037 were reported injured in the riots, mostly because of the tossing of rocks, bricks, and other projectiles.

Media and activist attempts to erase the destruction and ferocity of the uprising, by either ignoring the rebellion or by painting it as “93% peaceful protest” as CNN has repeatedly done, are an attempt to invisibilize the contributions and sacrifices of the predominantly (though not entirely) Black and Brown youth who led these attacks. It is disgusting, racist, elitist, and embarrassing.

In addition to being an insult to those who gave their lives for this struggle, the other sad effect of this whitewashing is the betrayal of the movement’s prisoners, of which there are many. If the uprising’s confrontational nature disappears in the public mind, so too do its prisoners. Readers are strongly encouraged to check out uprisingsupport.org for ways to support movement prisoners in your state, and also to engage deeply with the tidal wave of new writings by Black anarchists and revolutionary abolitionists that sprang up during and after the uprising.

North Carolina, May – September 2020

May 29th, Charlotte – Hundreds of demonstrators surrounded a police precinct on Beatties Ford Rd in west Charlotte. Members of the crowd physically beat and attacked individual officers, forcing them to hide in the precinct. After police returned in riot gear, tense street fighting occurred, with people pelting the precinct with rocks and hurling back tear gas canisters. Demonstrators failed to breach the precinct. A nearby grocery store was also looted.

May 30th – Many thousands of protesters descended upon downtown Raleigh, initially in response to a publicly called-for demonstration. The crowds broke into multiple smaller but still significant groups spread throughout the downtown area, dividing police forces and shutting down intersections. The protest escalated into the night, with rioting lasted long into the evening, destroying almost every shopfront along the main Fayetteville St., looting dozens of stores, and completely or partially burning a number of others. Rioters continually held ground against police assaults, forcing back police and focusing particular rage against the courthouse and jail.

May 30th , Fayetteville – Hundreds gathered in an initially peaceful protest along Skibo St., with J. Cole and the mayor making an appearance and calling for peace. Ultimately this too broke out into property destruction, however, as demonstrators reached the Market House downtown, a historic building where slave auctions occurred. Protesters set a fire in the building and fed it with wooden pallets, while others smashed businesses. Looters also broke into Cross Creek Mall.

May 30th, Greensboro – A protest beginning near the Civil Rights Museum on Elm St. grows and eventually moved through the city and shut down both directions of I-40. Later on the crowd fought police with rocks and began looting.

May 30th, Durham – Protests began in Durham around 1 p.m., where hundreds gathered on East Chapel Hill Street and Morris Street to protest in solidarity with Floyd. Local leftist politicians were on scene and emphasized the peaceful nature of the demonstration. People went home before dark.

Early Morning May 31st – Governor Roy Cooper activated the National Guard and deployed 450 troops to various cities to help local police quell the uprising. In a state of bewildered idiocy, Cooper declared, “I fear the cries of the people are being drowned out by the noise of the riots.”

May 31st, Asheville – Hundreds of protesters march onto I-240 and block both directions of the interstate. On I-240 westbound, the police meet protesters with rubber bullets and tear gas. This is the 1st deployment of tear gas by APD on a public protest in Asheville’s history. Upon returning to Vance monument downtown, police in riot gear meet them with rubber bullets and tear gas. Protesters respond with kicking tear gas canisters back and throwing water bottles and fireworks.

May 31st, Wilmington – Hundreds of people gathered near historic Wilmington City Hall at 8 pm. The police arrived in fifteen minutes and used tear gas to disperse the crowd.

May 31st, Raleigh – Smaller-scale rioting and confrontations with the National Guard continued into the night. According to Raleigh PD’s after-action report, during the week of May 30th there were 14 officers injured, 17 police vehicles damaged, over 200 reported incidents of burglary and property damage, and six arsons.

May 31st, High Point – Protesters blocked roads and broke windows of businesses. Police used tear gas to disperse the crowd. On June 1, the city issued a state of emergency and a curfew.

May 31st, Greenville – More than 1,000 people demonstrated. The protest “turned violent,” with 31 businesses damaged, 13 police and sheriff cars damaged, two small vegetation fires set, flags overturned, and damage to the courthouse. Officers were injured by rocks and bottles.

June 1st, Durham County – Arsonists destroyed part of the historic Stagville Plantation house, which was once North Carolina’s largest pre-Civil War plantation. The plantation had been maintained for “educational purposes.” No one was caught.

June 1st, Durham – About 60 marchers blocked the Durham Freeway in protest.

June 1st, Asheville – Thousands of protestors meet in front of the police station downtown to confront the police and hold space. After hours of shouting, police fire tear gas and flash grenades into the crowd. After gassing the crowd for about 4 hours, cops retreated, but the crowd stayed on to smash businesses and hotels, and throw up graffiti in the heavily gentrified downtown district.

June 1st, Charlotte – Approximately 200 protesters marched in Uptown Charlotte, some throwing rocks and fireworks at police.

June 2nd, Charlotte – A crowd of thousands of protesters in Uptown Charlotte threw bottles at police and blocked light rail train tracks. Police fired pepper spray and stun grenades at protesters, blocking them from taking over Interstate 277.

June 3rd, Durham – A crowd of between 500-1,000 marched through downtown and by the jail. The group then split up, with several hundred staging a die-in to block traffic in front of the police HQ, and several hundred others marching onto highway 147 and painting anti-police slogans, ultimately all reuniting later on E. Main St.

June 3rd, Asheville – Police make national news by destroying an autonomous medic station in downtown, after gassing crowds who refused the curfew dispersal order.

June 15th, Durham – After Durham’s lefty City Council voted to increase police funding, a group of protesters set up a tent occupation of the sidewalk in front of the police headquarters, demanding more funding instead be put to social services and housing. The tents served as a mutual aid hub and lasted 33 days, though efforts to expand into the street were shut down by cops.

June 19th, Raleigh – Protesters in Raleigh used rope to pull down parts of a Confederate monument after marching in celebration of Juneteenth. Protesters hung one soldier statue from a traffic pole at the corner of Hargett and Salisbury streets. Another statue was dragged through the street and set in front of the Wake County courthouse. Protesters nationwide destroyed or tore down dozens of Confederate and other racist monuments throughout June and July, and eventually over a hundred more were brought down by city governments attempting to avoid similar direct action in their own towns. This followed the 2017 destruction of a Confederate statue in Durham by anti-racist protesters after the battle in Charlottesville, and the tearing down of the Silent Sam statue in Chapel Hill in 2018.

June 24th, Durham – Dozens of drivers on I-40 slowed to 10 mph for exactly 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the time it took for Derrick Chauvin to murder George Floyd, thereby backing up traffic for hours.

July 18th, Durham – A group of about 75 people marched from downtown Durham to the former police headquarters on Chapel Hill St. One group draped two vertical, 50ft banners from the roof, declaring “Abolish” and “Reclaim,” while another began a choreographed performance, and others entered the building in an effort to seize and hold the space. When a conflict broke out with a right-wing photographer, police charged the group outside, ultimately dispersing the crowd and arresting and charging 23 with felony riot charges. Pamphlets handed out by the protesters declared their intent to hold the building long-term and run it as a space for mutual aid and popular radical education.

July 20th, Durham – Also in response to the City Council’s decision to increase the police budget, including $220,000 for a new shooting range for the Sheriff’s Office, an anonymous group vandalized two architectural firms involved in building the shooting range. They declared in a public statement, “We paid a visit to two architectural firms contracted to renovate said shooting range, who in their greed and complicity have chosen the moment of a black-led movement against police murder to actively aid the police in firearms training. RND Architects, off University Blvd, and Coulter Jewell Thames PA, at 111 W. Main St. in downtown, were smashed out and left painted, as a soft encouragement for them to do business elsewhere.

July 24th, Roxboro – Anger erupted after police murdered 45 year old David Brooks, Jr. Repeated protests occur over the next few days and weeks as the mayor of the small town declared a state of emergency.

August 28th, Raleigh – An earlier peaceful protest of about 1,000 people bled into the evening, as hundreds of protesters continued to march on downtown. People eventually targeted government buildings with graffiti and red paint, and tore down barricades outside of the Wake County jail, chanting along as prisoners inside banged on their cell windows.

August 29th, Durham – In solidarity with the renewed uprising in Kenosha, Wisconsin after the police shooting of Jacob Blake, over a hundred protesters marched through downtown Durham, smashing windows at the jail, and painting city walls with anti-police slogans.

September 5th, Durham – According to the Durham County Sherriff’s Office, “For the second weekend in a row, protesters gathered and marched to the Durham County Detention facility and damaged the building. On the evening of Saturday September 5th, a group of people came to the Durham County Detention Facility and threw objects at windows shattering glass and creating a public safety hazard.”

September 23rd, Durham – Around 100 people marched in downtown Durham in a protest in solidarity with Breonna Taylor, spray-painting anti-police and anarchist slogans and smashing businesses and a government building. The police chief said to media, “We were prepared last night for some of our usual types of protests with minimal staff, but certainly we were not prepared to respond to the level of activity that we did last night.”

September 26th, Raleigh – Several hundred people gathered at Nash Square in protest after a Kentucky grand jury decision not to charge the police murderer of Breonna Taylor. They then marched through downtown, spray-painting slogans and smashing windows. A group set up a huge projector with video of Breonna Taylor on a wall opposite the jail while others painted its walls. One woman said to the media, “People are angry. We aren’t seeing any change,” she said. “We’ve been protesting peacefully and it’s not paying off.”

Notes

- Tony McDade was murdered by police on May 27th, 2022, just 2 days after George Floyd was killed, at the Leon Arms apartment complex in Tallahassee, FL. Tony was a trans man and used he/him pronouns, though he was incarcerated in a “women’s” federal facility with Shawn years earlier.

- His name is David Elmakayes, and in June of 2022 he was sentenced to 15 years for blowing up an ATM and illegal possession of a firearm during the “civil unrest” in Philadelphia. Philanticap.noblogs.org and uprisingsupport.org have more information on how to support him.

Some Texts Worth Checking Out

A Nation on No Map: Black Anarchism and Abolition, by William Anderson (AK Press)

As Black as Resistance, by William Anderson and Zoé Samudzi (Ak Press)

Anarkata, by Afrofuturst Abolitionists of the Americas

Black Anarchism: A Reader, from the Black Rose Federation

Burn Down the American Plantation, by the Revolutionary Abolitionist Movement

How It Might Should Be Done, by Idris Robinson

The Revolutionary Meaning of the George Floyd Uprising, by Shemon Salam and Arturo Castillon

Race and Organization After the George Floyd Uprising, by Shemon Salam

Black Armed Joy: Some Notes Towards a Black Theory of Insurrectionary Anarchy

Download Zine