Zine :

Lien original : par Chris Chitty, via Blind Field

Tomorrow will mark the first anniversary of Chris Chitty’s death. Chris was a radical thinker, committed activist and scholar, and a cherished comrade. As a queer Marxist and prolific writer, Chris produced incredibly exciting work about sexuality and the history of capitalism, much of which is yet to be posthumously published. His writing was fearless, tenacious, and antagonistic. Perhaps the world was not ready for it – or at least that was the world to which we lost him. In honor of our friend, we have assembled a version of Chris’s ongoing project, “The Antinomies of Sexual Discourse.” The following was written in 2012, and would undergo another series of revisions, along with most of Chris’s writings, until the spring of 2015. Here we find the foundation of his project, and an opening to scholarship for which there remains a future.

~

To the extent that our lives are bombarded, minute by minute, with advertising come-ons, the latest lyrical euphemism for a sexual act and gossip of the affair of some acquaintance or media superstar, and to the extent that the critique of sexuality has become thoroughly and institutionally routinized, one is tempted to state an obvious fact: sex has become excruciatingly banal. Sexual practices once considered socially marginal or extreme have become the topic of a sort of bored, vapid cultural chatter and empty boxes on the growing political checklist of diverse persons in need of “tolerance.” The obsessional compulsion to speak or listen to a constant stream of sexual discourse might be a defining feature of our cultural moment in the wake of the 1960s social movements which contested the established sexual order and social conformism of post-war culture in American and European societies, suggesting that the simple wisdom of world-weary cosmopolitans — that “so little is new under the sun” — misses something essential about this cultural form and the historical conditions for its emergence. In spite of its banality, why does sex persist as an object for collective cultural enthrallment?

Perhaps contemporary sexual discourse has assumed the dimensions of what Peter Sloterdijk has called “cynical reason,” an enlightened form of false consciousness which eludes traditional modes of ideological critique. At first blush, this concept seems to cast some light on many experiences that one may encounter in everyday life. How many of us have found ourselves trapped in an amorous relationship, rehearsing a collection of clichéd lines about fidelity or romantic interest, which we know all too well maintain a dubious correspondence to reality, as if we were the first ones to have such experiences? How many of us have then experienced the heartache when such lofty aspirations come to grief upon the harsh reality of desire, as if it were a profound or singular disappointment? It strikes me that there are, however, many features of the contemporary cultural experience of sexual desire that escape this admittedly suggestive critique of the “as if” of cynical reason. It remains to be explained how the “liberation” of human sexuality, which may turn out to be a new form of social domination in its own right, ever became confounded with human emancipation as such or, at the very least, some cheap substitute for the latter. This problem presents two central questions for the present inquiry. First, why have theoretical elaborations of the body — as gendered, racialized, pathologized, sexualized etc. — been so central to philosophical projects which have sought to abandon the critique of capitalism as the objective totality structuring human life? Second, why have these accounts been so crucial for political analyses on the Left seeking to deny the subjective project of transforming the world and creating a new humanity?

The above provocations demand an account not only of the reification of sexual desire [1] but also of the way in which what was once a mere (but by no means unproblematic) opposition between nature and culture has now become an antinomy in which the same underlying social reality is experienced simultaneously as opposites and an exploration of the way in which discourses on sex and sexuality constitute the locus classicus of this field of antinomic thought about nature and culture. It is only by historicizing these antinomies of sexual discourse as internal to a late and unsettling stage of capitalism — of the “cultural dominant” or “postmodernity” [2] in which all pre-capitalist forms of life have been eliminated and collective human activity shapes the entirety of the world down to the vicissitudes of sexual desire — that the category of nature itself can be said to have been liquidated from our cognitive map, also draining its opposite term, culture, of its previous significance or rather, dissolving the cultural into the mode of production of late capitalism in general where the predominant form of work is widely considered to be “immaterial” and the service sector employs the vast majority of the workforce in core capitalist countries. Put simply, at stake in this antinomy between nature and culture, in which both threaten to vanish into the horizon of the unthinkable, is also that old dialectic between humans and nature, the category of labour itself, leaving us with uncertain prospects for some new, emergent political subject.

I. Commercium Sexuale

If Karl Marx was able to articulate the way in which labour, as both a mental category of human activity and a material dialectic between human societies and nature at once diachronic and synchronic, provides a vantage point for considering the totality of capitalism in which the whole character of society can be seen to be alienated through its labour, and if he was equally able to conceive of a situation in which this labour could become emancipated, what horizon, if any, does the sexual relationship open up for a critique of capitalist society and for the possibilities of human emancipation? Marx himself makes a striking argument in the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts to which he would later return in the Communist Manifesto. In the Manuscripts, he spares no scorn in criticizing the “vileness” of the Utopian Socialist programme for attempting to elevate private property to a principle of “positive community,” thus, radicalizing the present reality of social negation and alienation into a universal abstraction in their vision of the future. This aspect of their thought is nakedly revealed in the fantasy of a “community of women.” Marx writes,

In the relationship with woman, as the prey and handmaid of communal lust, is expressed the infinite degradation in which man exists for himself, for the open secret of this relationship has its unambiguous, decisive, open and revealed expression in the relationship of man to woman and in the manner in which the direct, natural species- relationship is conceived […] It is possible to judge from this relationship the entire level of development of mankind (Marx, Early Writings, 347, emphasis mine).

Like labour, the sexual relationship is a material dialectic between human societies and the biological fact of their existence, a diachronic feature of our social reality because it is essential to the existence and survival of the species. Similarly, the sexual relationship has an empirically demonstrable synchronic dimension, and it is for this reason that ethnographic analysis has for well over a century studied kinship structures as the most elementary building block of different forms of human society. As a mental category, the sexual relationship appears as an objective, natural species-relationship which, as Marx writes, “demonstrates the extent to which man’s natural behavior has become human or the extent to which his human essence has become a natural essence for him” (ibid, 347). As the two poles of the dialectic between humans and nature, labour and the sexual relationship predate capitalism but are categorically transformed in societies dominated by the commodity form. How exactly is the sexual relationship transformed by capitalist society?

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx revisits his argument from the Manuscripts in order to skewer bourgeois indignation at the Utopian Socialist proposition of a “community of women” as a self-undermining position because “marriage is in reality a system of wives in common” and “the abolition of the present system of production must bring with it the abolition of the community of women springing from that system, i.e., of prostitution both public and private” (Marx-Engels Reader, 488). Without too much difficulty, we might read his line of thought as a determinate negation of both the utopian socialist libidinal fantasy of wife-swapping and the bourgeois institution of marriage, that is, as an attempt to mobilize each position as a critique of its opposite ideological number. In a footnote to the above passage from the Manuscripts Marx makes this dialectical move explicit, “Prostitution is only a particular expression of the universal prostitution of the worker, and since prostitution is a relationship which includes not only the prostituted but also the prostitutor — whose infamy is even greater — the capitalist is also included in this category” (Early Writings, 350). The bourgeois is correct in assessing the degradation into which women would be thrust under conditions of common ownership, but the Utopian Socialists have exposed the secret of bourgeois marriage itself — as traffic in women and the most ubiquitous institution of private property — by pushing the tendencies of this institution to their limit. For Marx, the construction of a truly communist society implies the negation of both the institution of marriage and that of prostitution, which turn out to amount to the same thing on different social scales.

There is an extraordinary exception to the above account, which must not escape our attention, from Marx’s correspondence with Friedrich Engels in 1869. The two comrades discuss the nascent homosexual movement for the abolition of the Prussian State’s increasingly harsh laws against sodomy after Marx shares a copy of Karl-Heinrich Ulrichs’ pamphlet Urnings with Engels. In a response from June 22 of that year, Engels casually references the pamphlet in relation to the public affair of young Jean Baptiste von Schweitzer, a member of the German Workers Association, who was convicted of sodomy in 1862 for having sex with another man in a city park and nearly purged from the organization if not for the intervention of Ferdinand Lasalle. Because of the latter’s passionate defense of his comrade before the Workers Association, the former rose to position of president after Lasalle’s death in 1864. Though Engels writes that the pamphlet defending sodomy as the result of a natural in-born tendency among particular men contains “extremely unnatural revelations,” he marvels that homosexuals have discovered “that they are a power in the state.” He begins to envision the slogans of this new “party” in terms of a war against “poor frontside” men, such as him and Marx, with their “childish penchant for females”: “guerre aux cons, paix aus trous-de-cul,” declarations of the “droits du cul.” [3] I do not raise this text to denounce or apologize for its prejudice, as some commentators have done. Nor do I believe it is the task of criticism to play the role of what Zizek has called the “philosophical police” (Defense of Lost Causes, 98) with some overdetermined hermeneutics of suspicion, as others have done. [4] Exposing bigotry has rarely provided a very compelling raison d’être for critical theory, and such issues are better dispatched with in other registers anyway. I would like to suggest that we might instead, by suspending such judgments, read no small amount of amusement in the 49 year old bachelor’s flights of fancy concerning the burgeoning anti-sodomy movement and the cause of homosexuals, not to mention the cheeky fantasy that he and his 51 year old companion might have “to pay physical tribute to the victors” if not for being “too old.” Far from articulating a sense of panic at some monstrous crime against nature, the letter and its winking use of double-entendre seems much closer to a humorous fascination with the categorical limit that homosexuality posed to the established sexual order of things. Homosexuality, a term coined in this very same year, thus casts a shadow over what is, above all, an intimate correspondence between friends — as in a black mirror, reflecting the increasingly complex social contours of life within capitalist society, the difficulties of political setbacks with social democrats, concern for the younger generation of revolutionaries and the fading of masculine beauty and sexual vigor with age — from some distant point in the future, faintly troubling the assumptions and libidinal investments of its historical present from afar.

We might conclude this exploration of the structural analogy of sex with labour by turning to Georg Lukács’ analysis in History and Class Consciousness of the process of reification in which all physical and psychic human qualities are haunted by the “ghostly objectivity” of the commodity, which is all the more remarkable for the fact that he had not read Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts until after writing this work. He writes that the commodity:

stamps its imprint upon the whole consciousness of man; his qualities and abilities are no longer an organic part of his personality, they are things which he can ‘own’ or ‘dispose of’ like the various objects of the external world. And there is no natural form in which human relations can be cast no way in which man can bring his physical and psychic ‘qualities’ into play without their being subjected increasingly to this reifying process. We need only think of marriage, and without troubling to point to the developments of the nineteenth century we can remind ourselves of the way in which Kant, for example described the situation with the naïevely cynical frankness peculiar to great thinkers.

“Sexual community,” he says, “ is the reciprocal use made by one person of the sexual organs and faculties of another…marriage…is the union of two people of different sexes with a view to the mutual possession of each other’s sexual attributes for the duration of their lives.” (100).

Lukács does not consider this reification of sex and marriage to be a central antinomy of bourgeois thought, [5] for this rationalization of the world is limited by the fact that it appears within capitalist society as a set of “natural laws” within a totality that is actually ruled by chance, a totality which only comes into view and makes itself felt during a crisis. In fact, the omitted portion of the above quotation from Kant’s Metaphysics of Morals delineates a clear distinction between natural and unnatural commercium sexuale, these latter being sex with “a person of the same sex or an animal of another than human species…unnatural vices (crimina carnis contra naturam) that are also unnamable” (Die Metaphysik der Sitten, Pt. 1 § 24, ).[6] Although Lukács asserts that capitalism leaves us with no natural form whatsoever in which human relations or desires can be cast, his argument is precisely that this reification of sexual desire — which would include homosexuality as much as heterosexuality — appears to bourgeois thought as an unproblematically natural order.

It is important to remember that the sexual liberation movements of the West occurred at the height of the post-war economic boom. Despite tendencies otherwise, these movements may have given us the terminal point of the libidinal projections of bourgeois fantasy and Utopian Socialists centuries before: the prostitution of our bodies and minds to the impersonal logic of markets. However, to relinquish the kernel of hope that capitalism really contains the new society “in the womb of the old” in abandoning the tired husk of this old-fashioned metaphor strikes me as the central political peril of the present age in which our society threatens the human and ecological future of the planet with disaster. If we can agree upon this fact, then we must proceed to think the twin crises of sex and the family as sewing the seeds of psychic lack and social dependency out of which a new garden of human relations could be made to flourish. We cannot yet grasp the future subject who would tend this garden or what form the new society would assume, for the present society is plagued with antinomic thoughts, crowding our perspective and confusing our political orientations. The once clear articulation of a class or sexual standpoint from which the totality of capitalism could be understood, indeed had to be understood for that class or sexual standpoint to assert herself — theorized by Lukács as the subject-object union — appears to have vanished in the overgrown thicket of postmodernity, where we are left with a great many articulations of identity positions with partial claims on social justice but no central antagonism structuring the political field.

II. Antinomies of Time

Our period of capitalism can be differentiated from previous capitalist societies by tracing the developments of multinational corporations, a global market and division of labour, mass consumption and the centrality of finance capital in the global economic system, which is all suggestive of something like Ernest Mandell’s thesis on late capitalism. Discourses on sex have not been articulated from a position outside or above this history of capitalism and its attendant set of contradictions; rather, they have taken shape and generated a set of philosophical objects within the very unfolding of this history. At first glance, it is difficult to situate sexual discourse within this impersonal global economic system. As Fredric Jameson has pointed out, the totality of this new period of capitalism and its spatial and temporal horizons have become increasingly difficult to cognitively map, for the very reason that it is precisely the spatial division between inside and outside and our sense of history as such that are lost under late capitalism. In his influential essay “Periodizing the 60s,” Jameson links the development of the culture industry in the First World and the Green Revolution in Third World agriculture, as “a process in which the last surviving internal and external zones of precapitalism — the last vestiges of noncommodified or traditional space within and outside the advanced world — are now ultimately penetrated and colonized in their turn. Late capitalism can therefore be described as the moment in which the last vestiges of Nature which survived on into classical capitalism are at length eliminated: namely the third world and the unconscious” (Jameson, “Periodizing the 60s,” 207). He argues that the “liberation” of third world peasantries from the land and first world societies from the unconscious which inaugurated our present stage of capitalism are developments on the scale of the enclosures — analyzed by Marx as inaugurating the era of industrial capitalism — and similarly demand to be thought both negatively and positively at once. The present downturn has confirmed this thesis and we are now confronting a rising tide of joblessness in advanced capitalist nations, the appearance of shanty towns in California, and a so-called surplus population of one billion living in slums throughout what is now called the “global south.” Late capitalism’s ubiquitous culture industry has also progressively pillaged the repository of our drives and desires in fashioning a global consumer society through a process of both liberation and domination that primarily appears to us in the reified form of sex and the family in crisis.

How did what was once a mere opposition, between nature and culture become an antinomy of thought? Ethnographical accounts of hunter-gatherer societies have demonstrated that marriage regulations constitute the most elementary and universal form of exchange, so any history of the commodity form must begin with the position of women in such societies as the most primal scene of reification. It is worth considering the way in which Claude Lévi-Strauss resolved the opposition between nature and culture in consideration of the universality of the incest prohibition as the elementary structure of kinship. The problematic of his 1949 Elementary Structures of Kinship begins with the fact that no empirical analysis,

can determine the point of transition between natural and cultural facts, nor how they are connected…Wherever there are rules we know for certain that the cultural stage has been reached. Likewise, it is easy to recognize universality as the criterion of nature, for what is constant in man falls necessarily beyond the scope of customs, techniques and institutions whereby his groups are differentiated and contrasted. Failing a real analysis, the double criterion of norm and universality provides the principle for an ideal analysis which, at least in certain cases and within certain limits, may allow the natural to be isolated from the cultural elements which are involved in more complex syntheses. Let us suppose then that everything universal in man relates to the natural order, and is characterized by spontaneity and that everything subject to the norm is cultural and is both relative and particular. We are then confronted with a fact, or rather, a group of facts, which, in the light of previous definitions are not far removed from a scandal: we refer to that complex group of beliefs, customs, conditions and institutions described succinctly as the prohibition of incest, which presents, without the slightest ambiguity, and inseparably combines, the two characteristics in which we recognize the conflicting features of two mutually exclusive orders. It constitutes a rule, but a rule which, alone among all the social rules, possesses at the same time a universal character (Lévi-Strauss, 8-9).

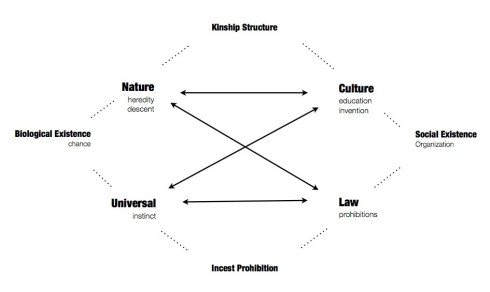

He presents his structural analysis of kinship as a solution to the problem that it is both impossible to demonstrate the universal prohibition of incest as either entirely a biological imperative of the human species or an entirely cultural norm in which the prohibition’s universality would become incomprehensible. Nor is the incest prohibition merely a “composite mixture of elements from both nature and culture” (ibid, 24). Lévi-Strauss proposes that the incest prohibition is a “link” between man’s biological and social existence, “less a union than a transformation or transition. Before it, culture is still non-existent; with it nature’s sovereignty over man has ended. The prohibition of incest is where nature transcends itself…It brings about and is in itself the advent of a new order” (ibid, 25). I would thus like to present the following Greimas Rectangle as the sociological model of social power.

Figure 1. The Elementary Structure of Social Power

Lévi-Strauss resolves the apparent contradiction at the heart of the incest prohibition as “the only possible basis for a viable ethnology” by arguing that this prohibition is the only universal law, and therefore, kinship structures become the point of transition between nature and culture in humans, generating both a biological existence ruled by chance and a social existence characterized by organization. The central contradictions would therefore be along the axis of cultural universals, and that of natural laws.

We can immediately see how this elementary structure of social power has fallen apart within the present post-colonial system of social power where the culture industry has achieved a global, if not exactly universal, influence, eliminating the opposition between nature and culture itself, or rather, turning this into an antinomy. That the very concept of nature has vanished can also be seen in the fact that the very same hunter-gatherer societies in the Americas who formed the basis of Lévi-Strauss’ study in Elementary Structures of Kinship have been eliminated from the face of the planet, placed within “Forest preserves” or currently run casinos on their reservations. Also, the very principle of natural law espoused by every variation of social contract theory, which established the legitimacy of bourgeois liberal states has been exposed as a fiction by the unparalleled number of stateless persons, for whom this present system can only find a place in camps. Likewise the immigrants arriving upon the shores of advanced capitalist countries from the global south discover that it is only by surrendering their “natural rights,” by risking the precarious position of being a sans papier and exposing themselves to the caprice of power without legal protections, that they can find work in these States.

As a mental category, our above dialectical treatment of the sexual relationship begins to confront a set of difficulties concerning its periodization, for we are presented with a fundamental antinomy of postmodernity between temporal continuity with the past and impassable historical lacunae. We need only think of the contemporary conviction of evangelical Christians that the Biblical account of kinship among Semitic nomads (who for instance, practiced polygamy) and the allegorical figures of Adam and Eve in the Judaic creation myth (which, if read literally, implies some form of primal incest between the first mother and her sons or between brothers and sisters) provide the basis for a defense of the modern institution of monogamous marriage. All the while, these same Christians doggedly assert that the Christ figure inaugurates a sort of epistemic break between “Old Testament” and “New Testament” onto-theological orders, invalidating the Mosaic law supporting the institution of polygamy. The recently proposed death penalty for convicted homosexuals in Uganda, resulting from decades of American evangelism in this region, is one symptom of this “globalized” antinomy; that of Thabo Mbeki’s catastrophic AIDS denialism for nearly two decades in South Africa is another, but it is also the ideological the flip-side of George W. Bush’s “abstinence” only sex-education policy in the US, which is a catastrophic form of AIDS denialism in its own right. This temporal antinomy is not isolated to Christian thought, however, and it bears noting that although Foucault insists in L’usage des plaisirs (1984) upon the fact that the Ancient Greeks had no category for thinking sexuality as such, this notion being a thoroughly modern invention (L’usage, 50), his analysis of aphrodisia relies nevertheless upon the historical findings of Sir Kenneth Dover’s 1978 Greek Homosexuality, which, as the title suggests, argues that Greek culture maintained a “sympathetic response to the open expression of homosexual desire in words and behavior” (Dover, 1). In the ethnographic register, Claude Lévi-Strauss identifies the humorous absurdity of Margaret Mead’s belabored Freudian interrogation of her Arapesh informants concerning what they would think of a man who slept with his sister, breaking the taboo on incest, to which they responded, “so you do not want us to have a brother-in-law?” Lévi-Strauss is quick to point out “how much more penetrating is native theory than are so many modern commentaries,” providing “the veritable golden rule for the state of society” (Elementary Structures of Kinship, 485). It seems that modern thought is far less savage than it would appear. The modern notion of human sexuality is simultaneously experienced as a natural transhistorical category of social reality and as a particular configuration of discourse and political power punctuated by epistemological breaks.

The AIDS epidemic presents us with a post-modern transformation of our collective being towards death, which for Heidegger appeared as a purely contemplative dimension of Dasein. AIDS has inaugurated an antinomy at the heart of most fundamental notion of temporality, as a crisis of reproductive futurity in which birth, coming into being, is simultaneously experienced as death, passing away. We need only think of the fact that children are daily born with this disease to mothers in Africa who will shortly die, leaving behind a future generation of orphans in its wake. In advanced capitalist societies queer theory has responded to this crisis of temporality not by fostering concrete political projects, but by politicizing reason itself with the so-called anti-social critique. Leo Bersani, for instance, has even gone so far as to suggest that although “nothing useful can come from the practice,” “bug chasing” and “gift giving” among gay men who deliberately seek HIV seroconversion might be “interpreted as a mode of ascetic spirituality.” An “implicit critique,” he writes, of “ego-driven intimacy,” and the practice may serve as a model of “pure love” (Intimacies, 50, 55). In another register, Lee Edelman proposes in his recent monograph No Future that queers have a political imperative to self-consciously embody the death drive, to assume the mantle of abortion-advocating opponents of heterosexual reproductive futurity, under the banner of Edelman’s call to arms: “Fuck the children!” Queers must, according to this analysis, ironically become the monsters that heterosexuals fear most. During roughly the same period, HIV-infection rates among men who have sex with men (the only group for whom infection rates are still increasing in the US) increased 11% nationally, with the sharpest increases among young men, who are racial minorities and economically disadvantaged (“Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2005” CDC, June 2007). By refusing the possibility of an alternative future to that of reproduction, ‘No Future’ reflects the impasse of the bourgeois family’s reproductive futurity, which is unable to imagine offspring that are ‘unlike them.’ Thus, the most anti-social and oppositional politics to ‘marriage and family’ is nothing other than the oppositional term within an antinomy producing this whole field of problems. The powerful riptide of increasing rates of HIV and the prospects for an abortive future of humanity seem far too high a price to pay for such political vacuity and intellectual indulgence. But the temporal antinomy remans, and we must also begin to ask ourselves how any “safer sex” campaign could possibly compete with the multi-billion dollar bareback porn industry, which has always constituted the majority of straight porn, but which now disturbingly constitutes over 70% of all gay porn and is literally being downloaded into gay men’s fantasy structures, breaking a decades long industry taboo on shooting gay porn without condoms.

~

With broken historical links to pre-capitalist forms of life and uncertain ground for the articulation of some natural sexual desire outside the determinants of capitalist society, our relation to and discourse on sex is much more unsettling than the thesis of cynical reason suggests, for we are confronted with a social reality in which sexual desire has itself been alienated into a discursive, spectacular machine whose very function is to flirt with mass death through the affirmation of diverse forms of sexual freedom. This was the essential insight of Michel Foucault’s path-breaking 1976 study Volonté de savoir and the conceptual core of his case for a “biopolitical” stage of capitalist society. His argument for the proximity of our own sexual discourse with that of the victorians we — nous autres, victoriens [7] — are so fond of denouncing has now been abandoned by the self-proclaimed inheritors of his project, who have constructed a veritable postmodern scientia sexualis of their own in which a new antinomic formalization of desire has taken shape. It is here that the negative, prohibitive function of the sexual taboo can neither be considered to be the operative elementary principle of postmodern cultural production nor its predominant form of social domination, as it was once conceived by sociological thought in the tradition stretching from Émile Durkheim to Claude Levi-Strauss.

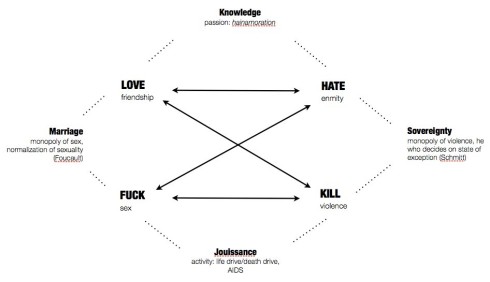

Thus we can see emerging a postmodern model of social power, with politics appearing to us in the succinct formulation of Carl Schmitt’s friend/enemy opposition, which implies Foucault’s formulation of the opposition between sex and violence. Thus, I present the following Greimas rectangle as a representation of this new set of oppositions, affinities and contradictions.

Figure 2. The Biopolitical Structure of Social Power

This biopolitical model of social power replaces the law of the sexual taboo, which was also the basis of Freud’s oedipal schema, with a play of force relations which constitute the organizational principle of postmodern societies. It provides both a model of social power without law and a concept of history that corresponds to the teaching of Walter Benjamin’s Thesis VIII On the Concept of History “that the ‘emergency situation’ in which we live is the rule.” Power would therefore be considered as a productive technology rather than as a prohibitive law and finds a worthy echo in Marx’s account of the struggle over the length of the working day, which we might remember required a transforming of the forces of production and the merciless submission of the human body, psyche and temporal rhythms to those of the “infernal machine.” It also finds an echo in Lacan’s notion of jouissance. In other words, we live in a society in which our collective desires are destroying both the planet and the future of the humanity, all under the injunction to “Enjoy!” which constitutes the succinct foundational principle for everything from the consumer society — content with its bread and circuses — to the exercise and organization of violence and sex in the form of a state monopoly on violence and sovereign ability to decide upon states of exception on the one hand, and a normalization of human sexuality which insures the regulation and discipline of the population on the other.

III. Spatial Antinomies

Aside from a collection of parochial world views — which will, in their turn, be revealed to be less remnants of some pre-modern cultural standpoint, but rather as bona fide contemporary cultural recoils — the Western experience is presently marked by a profound extension of sexual freedom and pluralistic affirmations of sexual difference; on the other hand, the conformity of sexual desire, however polymorphous it may be, with long-established social scripts has never been so pervasive. We need only think of the present political battle for same-sex marriage in the US and elsewhere, where those entrenched on either side of the barricades cling to the idea of “Family Values” as their most precious ideological weapon in service of their respective causes. During this most recent period of capitalist expansion, the media and advertising industries at the core of consumer societies have spread their influence and cultural products into the farthest reaches of the globe, generalizing this profound conformity of sexual desire to such an extent that to even speak of a “Western sexual experience” in the global, homogeneous cultural space of late capitalism seems ipso facto anachronistic. Are we not instead presented with a fundamental antinomy within the spatial logic of postmodernity between homogeneity and heterogeneity?

This is the suggestive proposition that Fredric Jameson puts forward in Seeds of Time: “our conceptual exhibit comes more sharply into view when we begin to ask ourselves how it is possible for the most standardized and uniform social reality in history, by the merest ideological flick of the thumbnail, the most imperceptible of displacements, to reemerge as the rich oil-smear sheen of absolute diversity and of the most unimaginable and unclassifiable forms of human freedom” (32). This is the problem with which I would like to begin an exploration of what will be conceptualized as spatial antinomies of sexual discourse.

These antinomies are most pronounced in the fields of thought in which the social order of gender and sex have been most formally rationalized. For this reason, gender studies, queer theory and their interlocutors constitute something like the locus classicus of the thought forms we must examine. This body of thought burst onto the scene of the culture wars of America in the late 1980s, modulating: ontologically, between natural or biological essentialism on the one hand and constructivism or performativity based on speech act theory, on the other; politically, between critiques of normalization and attempts to universalize the normal; socially, between the body as a site of individuation within a fixed identity and as the fulcrum for fluid collective affinities and identifications.

In 1990, at a conference of prominent feminists hosted by the University of California Santa Cruz, Theresa de Laurentis coined the term “queer theory” as an attack on various strains of radical feminism branded as “essentialist,” for insisting upon the gender binary as the primary organizational principle of social domination, and for supposedly ignoring the intersection of gender with sexuality and race. If it could be shown, as Judith Butler attempts in Gender Trouble–first published in 1990 –that the supposed material basis of gender is not automatically generative of particular desires, or phenomenological determinations of gender, but rather determined in language, the problems of woman’s representation (or lack thereof) before the law, her agency as subject of history, could be sidestepped through a critique of the embodiment of gender, as being a fluid set of subject positions along a continuum within an impersonal network of power. Butler was severely criticized after the publication of this work for the reason that her vision of the linguistic production of fluid subject positions appeared to argue that gender was completely malleable, if not somehow voluntary. Thus, accompanying the New Economy ideology of a cybernetic mode of production capable of unleashing a wave of dynamic growth and explosive productive energies is the idea that language rather than some combination of nature and cultural domination produces gendered subjects. Donna Haraway’s 1985 “Cyborg Manifesto” explicitly — though perhaps ironically — makes this connection between a cybernetic mode of production and the destruction of seemingly natural gender binaries, prophetically registering this later shift within feminist theory and praxis to anything and everything thought to be “queer.”

Although the critique of essentialism destabilizes the reification of sexual and gendered social order as being natural, it also realizes a different form of reification. The drive of the most radical strains of queer theory to disrupt all binary oppositions has developed an infinitely regressive tendency towards discovering ever more marginalized intersections of gender and sexuality. With the theory of the production of gendered subjects through language, the “ghostly objectivity” of the commodity has penetrated the very depths of the body and sex, which are now considered — symptomatically — to be “plastic.” This is the implicit argument of de Laurentis’ later rejection of the very body of thought which she helped to found when she wrote in 1994 that ‘queer theory’ “has very quickly become a conceptually vacuous creature of the publishing industry” (‘Habit Changes’ differences 6, 2-3, 296-313). Michel Foucault once lambasted the hypothesis that the West has been marked by a long history of sexual suppression and the corresponding narrative of a progressive lifting of prohibitions on diverse expressions of sexuality. He writes in his 1976 work Volonté de savoir, “Perhaps no other type of society has ever accumulated — and over such a relatively short history — so many discourses on sex […] Concerning sex, the most long-winded and most impatient of societies may be our own” (46). [8] His conclusion? “The irony of this apparatus: it makes us believe our ‘liberation’ is at stake.” If the primary mode by which power is exercised over sex is not through silence and suppression but rather through the multiplication of polyvalent discourses on sex, the project of queer theory to pluralistically affirm and speak upon diverse sexualities represents a profound extension of this apparatus of power into ever more domains, to capture ever more subjectivities within the positive, productive mechanisms of power that compel us to speak about sex. A new formalization of desire has taken shape, in which the objects and subjects of sexual desire are coded by linguistic sequences — and the trope of “codes,” their decyphering, their reproduction and disruption abound in this literature — which are thought to determine subjects in the way that binary code produces the Internet.

On the other hand, the bestiary of biological essentialism has given us a whole host of figures from gay penguins at the San Francisco Zoo to sets of bio-identical gay twins, which are all used as support for the hypothesis that homosexuality is a natural biological fact. We might doubt whether or not a gene actually codes for social behavior, or whether penguin sociality has anything to do with that of humans. We may point out to these scientists — many of whom are well-intentioned homosexuals — that scientific facts have varied historically, supporting contradictory conclusions in different epochs, and we might even stress upon them the dark socio-political history of biological essentialism (associated with eugenics movements of one kind or another); however, the imperative to prove that homosexuality is natural or normal is also an attempt to prove that it is not a choice, that the objects of our desire are “out of our control.” In other words: an ideological reflection of the way in which capitalism shapes our lives through impersonal forces. The truth of this ideology is as a critique of the more voluntarist strands of queer theory. If geneticists are ever able to conclusively identify a “gay gene” with genetic screening or even manipulate its phenotypic expression, one can only wonder what the market would do with this fact.

Though we may agree that sexuality and gender are socially constructed, we must acknowledge that the very means of constructing it otherwise — or indeed disrupting the totality of the gendered and sexual social order — are out of our hands, and that no amount of “micro- politics” will ever change the lived daily reality of socially overdetermined biological sex, or the differential social burdens foisted upon biologically sexed bodies. We need only think of the way in which birth control has historically regulated and pathologized the female pole of the sexual relationship and the way in which this order of things — tinkering with women’s hormonal balances, surgically implanting intrauterine devices which can cause severe scarring and infertility, the targeting of women as carriers in venereal disease campaigns, not to mention abortion — appears to us as natural; whereas, proposals to regulate the male pole, such as recommending vasectomies as a normal course of medical care for all men and universal access to a reversal of the procedure, are labeled heavy-handed or fascist. The assertion of biological essentialism also shares with queer theory the assumption that gender and sexuality are determined by a sequence of code; whether this code is believed to be a particular sequence of proteins in human DNA passed down through the generation of our species or a codification of language, passed down historically through culture, fixing individuals into subject positions, both perspectives articulate a human social reality shaped by forces which escape our immediate control.

This field of antinomic thought has generated a central political contradiction between projects to universalize the normal and a politics of opposition to normalization. In a 1993 article for The New Republic, Andrew Sullivan set the national post-AIDS gay agenda as an explicit campaign for normality through an extension of the right to marry, the right to serve in the military and the right to adopt children. In many states, gay parents are currently able to adopt children. The Obama Administration has recently announced the inevitability of a repeal of the Clinton-era “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy barring military service to gay men and lesbians. For the last two decades, both the Evangelical Christian and Gay Rights movements have appealed to ‘love’ in order to trumpet the exact same cause celèbre: ‘Marriage and Family’ to the tune of over $130M in U.S. state ballot initiatives since Massachusetts became the first state to legalize same-sex marriage in November of 2003 (followthemoney.org). In spite of recent setbacks such as the repeal of Proposition 8 in California, victories in states such as Iowa signal that this legal barrier to living a normalized gay life shall also fall. Queer theory’s ontological thesis of non-essentialized sexual fluidity is paradoxically shared by the proponents of Evangelical Christian conversion therapy, but these latter derive far more radical political programs from this conviction than the former, and both will soon be steamrolled by the engine of progressive social tendencies in the US and will likely dissolve along with the fringe social movements that spawned them. Indeed, the normalization that queer theory opposes is a far- weaker form of social power, and their theorization of a feeble “micro-politics” of resistance is only possible in a political field no longer structured by a primary class antagonism. The growing wave of joblessness across the advanced capitalist world and among its youth in particular — who have in the span of months symptomatically transitioned from the hopeful media label “Millenials” to the despairing “The Lost Generation” — has already begun to eclipse the international headlines (NYTimes).

~

We live in a society that largely thinks of gender and sexuality as socially constructed along a continuum with diverse cultural expressions, but we can no longer conceive of how we would transform the present society into one rooted in different forms of human relations founded upon neither impersonal sex nor the old institution of marriage and family. In “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat,” Lukács writes in a cautionary tone: “The reified world appears henceforth quite definitively — and in philosophy, under the spotlight of ‘criticism’ it is potentiated still further — as the only possible world, the only conceptually accessible, comprehensible world vouchsafed to us humans. Whether this gives rise to ecstasy, resignation or despair, whether we search for a path leading to ‘life’ via irrational mystical experience, this will do absolutely nothing to modify the situation as it is in fact” (110). Because sex constitutes one of the most socially intense sites of the old antinomy between subject and object, perhaps, as the point of indistinction within this old opposition, the body has been central to the postmodern project to reject or sidestep the philosophical tradition of thought on the subject capable of transforming the world; it is for this reason also central to analyses that have abandoned the starting point of capitalism as the closed, objective totality structuring human life.

Of all the grotesqueries of postmodernity, perhaps the most insidious is the general opinion that the transformation of our bodies into commodities, the total colonization of our desire and drives by impersonal market forces and our general enslavement to an economy of flesh, is thought to be evidence of our “liberation.” I would like to close this discussion of the spatial antinomies of sexual discourse by suggesting the possibility of another antinomy between the concepts freedom and slavery in a world in which the practice of the latter has vanished along with the seemingly natural order on which it was based. Can postmodern sensibility still comprehend that famous opening line of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Du contrat social? “Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains.” Does such conviction still grip us today, and to what conclusions would it lead?

IV. Our Pornographic Attunement to the World and Utopian Desire

If Marx was able to conceptualize the work-relationship as a figure of universal prostitution, what is the analogous social form that would express this new field of antinomies around the body, sex, and language in our era? I would argue that our experience of the world, our postmodern attunement to the world — to borrow another concept from Heidegger — is profoundly pornographic. In our society of the image, pornography, which according to its Ancient Greek root (pornographia), is an illustration (graphō) in the place of (-ia) the prostitute (pornē), marks a fundamental transformation of this “oldest of professions” by the age of mechanical, and now cybernetic, reproduction. If Benjamin characterized the transformation of the work of art by film as a destruction of the object’s aura by the drive toward proximity, we might provocatively argue that the set of libidinal investments of late capitalism crystalized in this pornographic attunement to the world, are marked by a profound quality of melancholic manic-depression for this lost aura of sex. What else could explain the stupefying repetition that marks pornography as such a simultaneously frenetic and saddening cultural product in its own right? The revenue of the $13.6B US porn industry, the majority of which is generated on the other side of the Hollywood Hills in San Fernando Valley, CA, are larger than that of Hollywood, and also more than the revenues of professional football, basketball and baseball put together.Worldwide revenues from pornography exceed $97B, more than the combined revenues of the top seven internet companies combined. [9] 37% of all internet downloads, one quarter of all internet searches, and 12% of all websites are pornographic. [10]Situated within the culture industry, we might argue that the new cybernetic mode of production has, above all, given us a carnival of flesh unparalleled in its global proportions.

What are the formal and technical innovations of this cultural product over that of prostitution? With porn, the john is replaced with a camera. With the help of editing, the human body is cut up into thousands of visual planes, time is broken up into separate visual experiences of simultaneous action — here, the technique of the close-up permits glimpses, aspects, forensic fragments of the sexual act multiplying a visual experience into a sequence of moments and perspectives for potential erotic attachment. On the other side of this camera lens: millions. Here, its political aspect is revealed in mass participation as the radicalization of the utopian fantasy of radical human sexual community. Unlike the distinctively modern experiences of the cabaret, peepshow or pornographic movie theatre, this mass participation has become a private affair.With the aid of the camera and now cybernetic distribution networks we do not sense the millions of other eyes glued to this shimmering screen, and one’s singular experience of this image is not sullied by mass participation in it, permitting the libidinal fantasy of being the only one to have caught this act, to have it as one’s own: a definitively postmodern moment in which the mass participates through the mediation of technologies that have an individuating function, inclusion through separation. But the jouissance of sexual desire itself, as desire par excellence, has been alienated into this machine and because this loss is hidden from view — or perhaps hidden in plain sight — we don’t even know how to mourn it. However, if there should be a lull in the bland synth music that plagues this cultural form, we may hear the distant sound of sirens outside the window of the room, and in this intrusion of the outside world into our erotic experience, we might perhaps make the connection, however unconscious, between our collective social death and our detached sexual enjoyment. Melancholia.

Once the lost object is internalized, and here the object is precisely internalized through sexual fantasy and a subjective identification with the camera, the subject is structurally incapable of the “work of mourning” [Trauerarbeit]. <Depression and loss of work in general> The melancholic’s lost object is half-alive, since lost but persisting. To overcome this form of social death requires a project to portray these fragments of life worlds as dead, to foreground the painful and hidden loss, rather than burying it from view.

Our pornographic attunement to the world, of which the antinomies of some new postmodern scientia sexualis are only the intellectual expression, may have pushed the libidinal fantasy of the Utopian Socialists criticized by Marx to its limits, realizing “the infinite degradation in which man exists for himself.” If late capitalism has succeeded to the point of transforming our psychic drives and structures of desire, we have also lost whatever sense of enchantment the sexual relationship once had. If it is rather impossible today to actually envision what one would desire in another world, a world beyond capitalism, this is because human desire itself cannot escape the totalizing determinations of capital. However, this “crisis of desire” may be the condition of possibility for demystifying this other world beyond capitalism, and demystifying sex itself, so that a thought about non-genital, non-appropriative human love can be formulated. The goal: to think this pornographic attunement to the world positively and negatively at once, to embrace the possibility that even in the most individuated, alienated experience of one’s sexual desire — masturbating alone, in front of a computer screen, in the darkness of a bedroom — there is still a deep drive towards proximity with strangers in their most intimate moments — reality TV would here constitute a derived cultural form — a psychic lack striving for the Other. Is there a better allegory for the furtive energies currently animating our political climate after the decline of Socialism and well-nigh burnout of Capitalism? What we need now more than ever is not more sexual freedom. We rather need practical and theoretical emancipation from sexuality. At the limit point of our alienation from one another, lies the potential for communal being, for it within this pornographic attunement to the world that we might find each other once again, stripped of all sense of moral propriety and the sacredness of property that has become attached to the body as such. It is precisely this valance of the body considered as property, as private parts, as sex, that provides the ideological support for the legal and ethical proposition of all originary legal protections of private property. If such a thing as sexual desire itself has now been placed in common, how do we begin to liberate this potential.

Doubtlessly, such a project of discovering the lost life worlds which we are incapable of mourning and the task of representing the loss of any external position from which to evaluate our sex and our desire as natural — a task troubled by a deep seated cultural melancholia — are both essential to any attempt at understanding the utopian longings of the sexual liberation movements of the past, and perhaps, any contemporary project worthy of the name Utopia. It is here that Jameson’s project to show the structural analogy of Utopia and desire is indispensable. In a position he has named “anti-anti-Utopianism,” [11] Jameson subjects this concept of Utopia to a rigorously immanent critique or a determinate negation in order to extract truth from the ideologies of the various utopias and their detractors. He writes, “what these utopian oppositions allow us to do is, by way of negation, to grasp the moment of truth of each term. Put the other way around, the value of each term is differential, it lies not in its own substantive content but as an ideological critique of its opposite number.” A truly rigorous dialectical thought about a particular utopia requires that we acknowledge its position as a partial or ideological view of society as a whole, and that no utopian discourse is exempt from this. He continues, “[a]nother way of thinking about the matter is the reminder that each of these utopias is a fantasy, and has precisely the value of a fantasy — something not realized and indeed unrealizable in that partial form.” [12] If Utopias are by formal definition an imaginative rendering of a world that does not yet exist, such a rendering could only ever be partial. Paradoxically, if any particular utopia were realized, the original set of desires that make it appealing would presumably no longer exist in the other world for which we once longed. Utopian thought would then be structured like Lacanian desire which is non-compactifiable, or, in other words, the structure of Utopia is analogous to fantasy because the very impossibility of a fantasy’s realization endows that fantasy with its driving force. [13]

This thought — that utopia is structured like desire — is useful for clarifying another of Jameson’s sharp formulations: “the space of the utopian leap” or “utopian circularity,” which many have, following Benjamin, considered a “weak messianic power,” between some imagined future and the empirical present. The circularity of Utopia is most clearly articulated in Jameson’s demand of full and universal employment world-wide, “for it is also clear, not only that the establishment of full employment would transform the system, but also that the system would have to be already transformed in advance, in order for full employment to be established.” [14] However, the gap between a demand for something that would change the way the capitalist system functions and a present set of systemic arrangements blocking the very realizability of this desire is not, in the final analysis a “vicious” circle in Jameson’s account.

Both perspectives on Utopia or what we identified as the diachronic, casual, or ‘root of all evil’ perspective of Utopia on the one hand and the synchronic, institutional or constructive one on the other are imaginary constructions or “plays of fantasy.” [15] Both involve a dimension of pleasure, though the synchronic pole of the Utopian contains a pleasure akin to that of the tinkerer rather than that of the dreamer. [16] The situation only appears viciously circular from the diachronic pole of utopian desire, whose demand to eliminate some root of all evil is driven by the pleasure of wish fulfillment, whose very precondition is the likelihood of failure.

Jameson proposes that the synchronic or institutional pole — what I will call unsexy utopian politics [17] — is only possible once a Utopian wish circles back from the imagined future to hit the brick wall of synchronic reality in the current social, political and economic structures which make this wish a systemically impossible demand. Jameson’s conclusion is interestingly embracing the possibility of a sex-less Utopia, as in the 1970s film Zardoz. This collision of the diachronic into the synchronic, or this necessary failure of a utopian wish, is the very condition of possibility for a diagnosis of the present, and “allows us, indeed, to return to concrete circumstances and situations, to read their dark spots and pathological dimensions as so many symptoms and effects of this particular root of all evil identified [in the example] as unemployment. […] At this point, then, utopian circularity becomes both a political vision and programme, and a critical and diagnostic instrument.” [18] The failure of the utopian wish, which could only ever be a partial or ideological desire for a world without some overdetermined root of evil or without a particular structural contradiction enables the construction of another world because the experience of utopian circularity, although it is no less embedded in fantasy or desire, enables a critical-diagnostic programme. The utopian programme is also structured like desire because it takes pleasure in retooling the institutional arrangements and systemic configurations that must be in place for Utopian demands — which, properly speaking, would no longer be utopian — to be articulable. The vanishing horizon, or non-compacticity, of the utopian programme is that the more successful the institutional rearrangements and systematic reconfigurations are, the less utopian the demands on this transformed system seem.

In Jameson’s formal analysis of utopian texts, unsexy utopian politics turn out to be the central strength of utopian thinking:

The boredom or dryness that has been attributed to the utopian text, beginning with More, is thus not a literary drawback nor a serious objection, but a very central strength of the utopian process in general. It reinforces what is sometimes called today democratization or egalitarianism, but that I prefer to call plebeianization: our desubjectification in the utopian political process, the loss of psychic privileges and spiritual private property, the

reduction of all of us to that psychic gap or lack in which we all as subjects consist, but that we all expend a good deal of energy on trying to conceal from ourselves. [19]

“Model railroads of the mind,” Jameson writes, “these utopian constructions convey the spirit of non-alienated labour and of production far better than any concepts of écriture or Spiel.” [20] If the desubjectifying, anonymous and even boring work of the utopian programme successfully changes the world system such that a utopian demand is realizable, this process is also likely to transform the whole set of wants, needs and lofty aspirations that drove the utopian programme in the first place. These would surely appear as lackluster artifacts of a previous era in the light of the dawning other world. This is what I take Jameson to mean when he writes of “the loss of psychic privileges and spiritual private property.” The wish is no longer special or titillating, indeed, no longer a wish once it is realized. The privilege of an individual subject, or psychic wholeness is unmasked by the utopian process as the very function of our alienation from the social reality that our labour sustains, and which returns like a boomerang to determine us.

For the present inquiry: I’d like to ask how it is that the failure of the project of sexual liberation, which according to our analysis above has generated new modes of confinement through the extension of late capitalism into the very structure of sexual desire, might be the precondition for a politics beyond sexuality, for a desubjectifying or plebeianizing critical- diagnostic programme. If the antinomies which we have historicized above can be read as symptomatic failures of our ability to imagine a future and alternative modes of human relations outside the contradictions of late capitalism, how do we move to consider the synchronic or institutional aspects of the movements assembled under the inadequate heading of “sexual liberation”? This question places us back, with sharper analytical tools, into our original problematic: the urgency of practical and theoretical emancipation from sexuality. I’d like to take this project in the direction of an analysis that could break with the antinomies of sexual discourse in a way that would enable a reactivation the social content of historical forms of life that once strove toward a future beyond the mere reproduction of the order of things. These forms of life — like homosexuality for example — could then be evaluated, as standpoints from which the totality of capitalism has been directly challenged or called into question, rather than as challenges to some vague system of “normativity.” What alternative models to the family, re- organizations of urban and rural life, re-conceptualizations of pedagogy, and challenges to the prevailing form of human relationships in the military, political party and prisons were elaborated by the forms of life associated with homosexuality? Is the category of friendship a better standpoint from which to evaluate this history? The social content of these forms of life that I have in mind would be that which is not reducible to sex, those aspects of homosexuality which indeed, have very little to do with sexuality as such.

Notes

[1] On this note see Kevin Floydʼs recent attempt to synthesize Marxism with queer theory, Reification of Desire: Towards a Queer Marxism (2009).

[2] Cf. Fredric Jamesonʼs analysis in “Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism”

[3] “war on pussy, peace to the assholes “ and “rights of the ass”

[4] See Andrew Parkerʼs “Unthinking Sex,” Fear of a Queer Planet, 19.

[5] It appears in his essay within the section “The Phenomenon of Reification” and not that of “Antinomies of Bourgeois Thought”

[6] Hacket Edition, p. 87

[7] “We, victorians” is the best translation of this first section heading of Volonté de savoir, which is completely butchered with Robert Hurleyʼs translation, “We ʻother victoriansʼ” (VS 9; compare to History of Sexuality Vol. 1: An Introduction, 3). Nous autres, like its opposite term vous autres, is an emphatic we, denoting the enunciative position of those who are speaking, vous autres could be rendered with the colloquial “you people.” All translations from this work are my own.

[8] All references to this work are to the French. Translations are my own. The existing English translation is terrible.

[9] Google $22.68B, Amazon $21.69, eBay $8.39, Yahoo $6.53, AOL $3.42B, Netflix $1.59B, Earthlink

$775M, pulled from SEC filings.

[10] http://internet-filter-review.toptenreviews.com/internet-pornography-statistics.html and http:// thenextweb.com/shareables/2010/01/10/the-number-behinds-pornography/

[11] Archaeologies of the Future, xvi. This name follows Sartreʼs stance on Soviet-era communism

[12] “The Politics of Utopia,” 50.

[13] Cf. Lacan, Encore: Seminar XX; Lacanʼs humorous literary example of the non-compacticity of desire is the figure of Don Quixote, and his formal example is Zenoʼs paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise.

[14] “The Politics of Utopia,” 38.

[15] Ibid, 46.

[16] Ibid, 40.

[17] Ibid, 53: Jameson notes that confronting our anxieties about Utopia is central to dialectical thinking this term. Otherwise we risk falling back into the partial wish fulfillment structure of Utopian desire. The Utopia we desire may obliterate the desires that led us to it in the first place. Fredʼs example: the Utopian trope of a sex-less utopia, in Zardoz for instance is important to acknowledge, especially now that talking about Utopia has become fashionable and risks too much sexiness.

[18] Ibid, 38.