Zine :

Lien original : CrimethInc

En français :

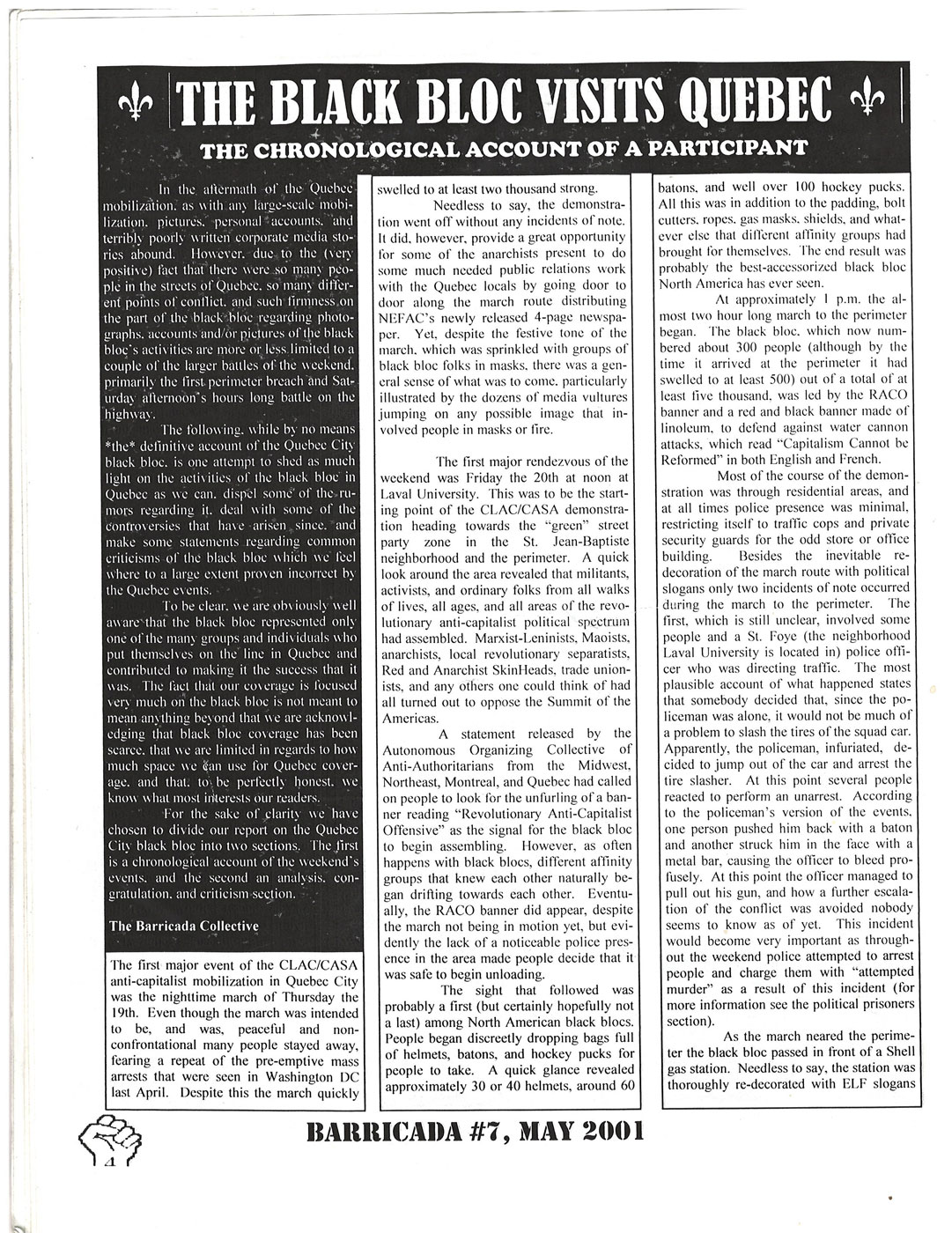

In April 2001, at the high point of the so-called “anti-globalization” phase of the worldwide anti-capitalist movement, anarchists from all around North America converged in Québec City to oppose a transcontinental summit intended to establish a “Free Trade Area of the Americas” (FTAA). The ensuing clashes arguably represent the culmination of that era’s powerful social movements. In the following narrative, a participant in the events in Québec City offers a blow-by-blow account of the epic street battles of April 20-21, including selections from the anarchist media coverage of that time. The result makes for exciting reading, to say the least, but it also an important educational document that has much to offer today’s anarchists.

From the protests against the summit of the World Trade Organization in Seattle at the end of 1999, at which the anti-capitalist movement exploded onto the global stage, to the demonstrations against the FTAA in Québec City, anarchist organizing and tactics experienced an historic renaissance in North America. The black bloc in Seattle had consisted of scarcely more than a hundred participants; while its actions were inspiring and influential to many people, they were also extremely controversial. By April 2001, however, anarchists and other anti-authoritarians had secured a central place for confrontational strategies in these actions.

The mass mobilizations in London, Seattle, Québec City, and elsewhere around the world were not simply reactive. Anti-capitalists went on the offensive, rallying broad coalitions to take the fight right to the doorstep of global trade organizations, interrupting their meetings and undermining their support structures. To understand this in the context of today’s movement against police violence, imagine if, rather than protesting whenever the police murder someone, opponents of police brutality repeatedly shut down the national conferences of organizations like the Fraternal Order of Police and the politicians who fund them, rendering it impossible for them to coordinate on a national scale and crystalizing a narrative of widespread public opposition.

As David Graeber recounts in The Shock of Victory, this approach proved to be extremely effective. The Free Trade Area of the Americas agreement was soundly defeated, despite an unprecedented police mobilization to defend the 2003 ministerial in Miami. While the reformist elements of the anti-globalization movement left a legacy that was eventually coopted by far-right nationalists like Donald Trump, anarchists proposed a transformative solution to the problems engendered by capitalism, a solution that retains its promise today.

The following account is adapted from a forthcoming memoir on PM Press, entitled Ready to Riot: A Chronicle of Anarchist Experiments in Militant Organization & Action, 1995-2010. For more like this, follow @batallonbakunin on Twitter.

“We Have Nothing, Destroy Everything! Onward to Québec City!”

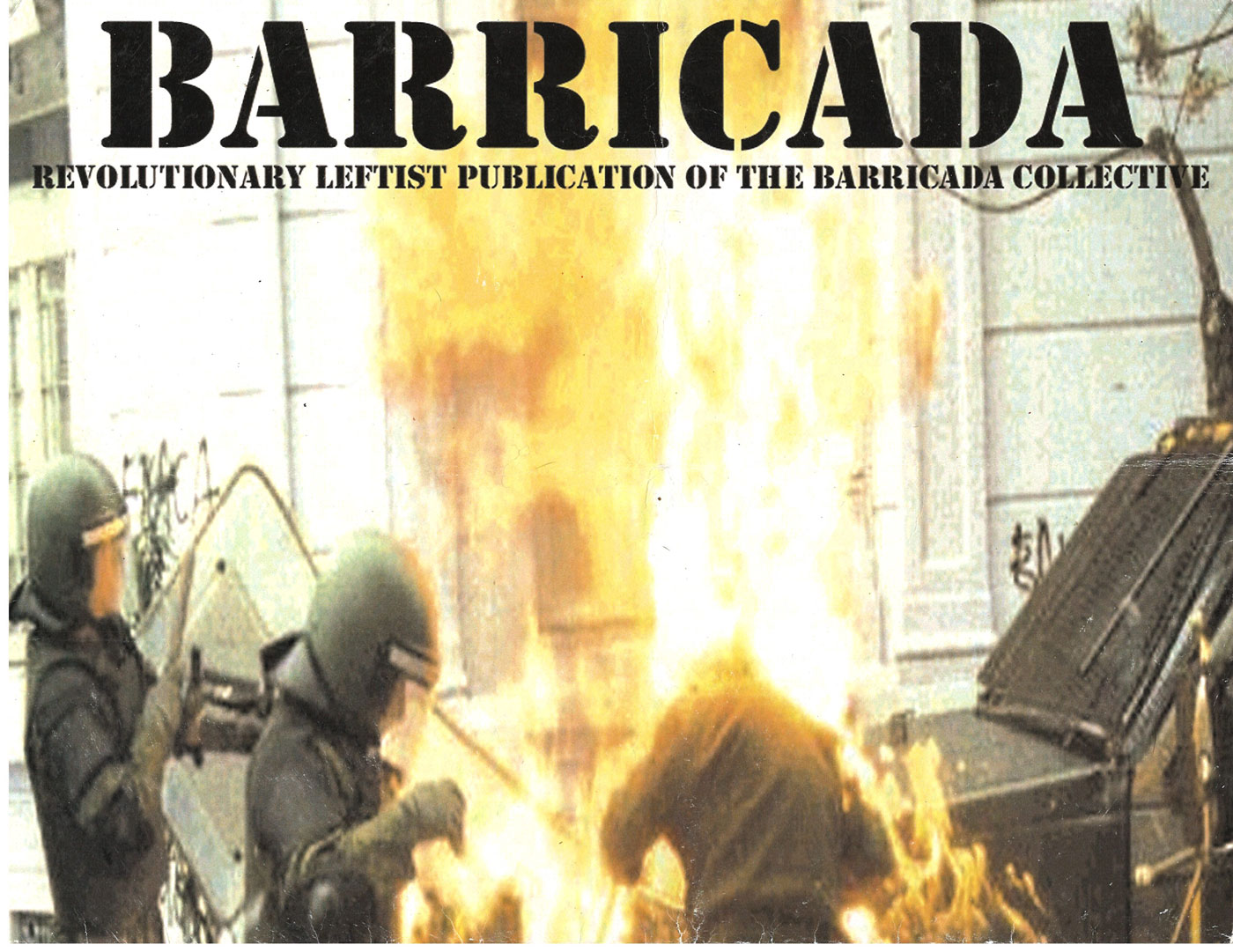

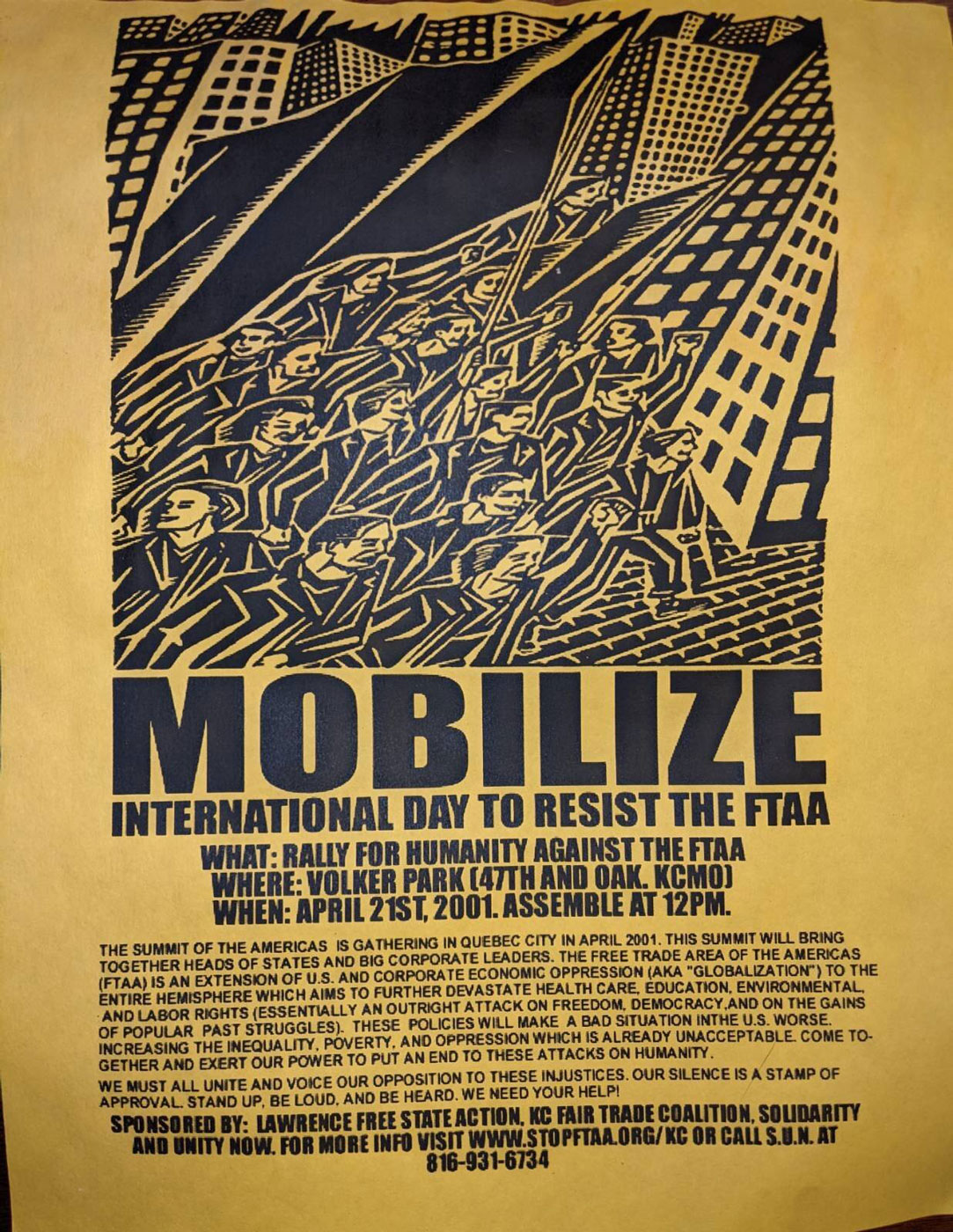

The following call to action was originally published in March 2001, in issue #5 of the monthly anarchist publication Barricada,1—the mouthpiece of Boston’s unabashedly confrontational Barricada Collective, which had also been instrumental in organizing the black bloc against the Bush inauguration a few months earlier.

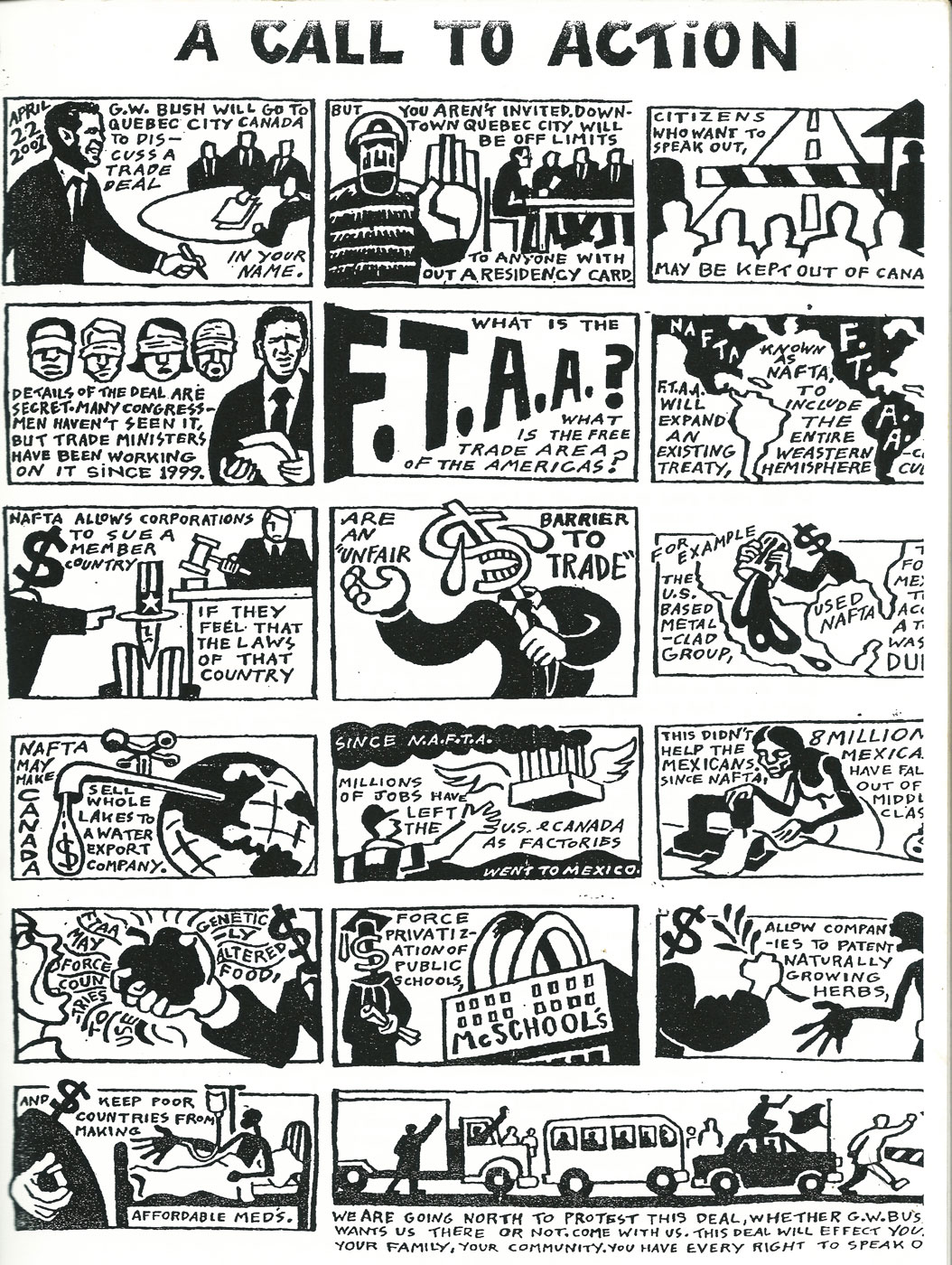

“On the weekend of April 20th to 22nd the ruling elites of the Americas will gather in Québec City to discuss the implementation of the FTAA (Free Trade Area of the Americas) and, to a large extent, the future of us all. The FTAA represents essentially an expansion of NAFTA to include the entire Americas region. The objective? To further clear the way for laws allowing corporations to sue member nations when they feel a government measure impedes “free trade,” to further attack the already fragile social safety systems we have, to pave the way for possible privatization of schools, hospitals, and all other social services, and to further consolidate the dictatorship of capital in the Americas.

It is the lives of everyone in the Americas they will be playing with at the summit in Québec City, the lives of every American (Northern, Southern, or Central) worker, peasant, unemployed, retiree or student. Yet, for some reason, the “democratic” leaders that govern us have neglected to invite us to this summit, or even to show us the texts they will be discussing for that matter. They have even gone as far as to build an enormous fence around a large part of Québec City to keep us out. All this has prompted many reformist organizations to protest, and they will be in Québec City to demand a “place at the table.”

Yet we, anti-statists, anti-authoritarians, anti-capitalists, and revolutionaries, will be converging on Québec City for a different reason. We are not interested in a place at the table of capitalism, or in providing a more humane and friendly face for what we know to be an inherently flawed system. We have a different vision, one of a society based on mutual aid and solidarity, where people are not robbed of the fruits of their labor, and where decisions that affect everybody are made by everybody, rather than by a select few. And, just as importantly, a society where people know who their enemies are, and are ready to stand up to them. We are interested in nothing less than the destruction of the “table of capitalism.”

The Summit of the Americas is an attack on all of us and must be treated as such. We must show the ruling elites of the Americas that we are ready to resist their attacks and fight back. We must show them that we are ungovernable and that no amount of police can keep them safe from the anger of those they oppress.

Friday April 20th is the day of action called by the Anti-Capitalist Convergence and the Summit of the Americas Welcoming Committee. Actions on this day will be divided into three “blocs.” A green bloc with no, or minimal, risk of arrest; a yellow bloc, for people planning to do civil disobedience; and a red bloc, for the “disturbance oriented” crowd.

We are thus calling on all militant revolutionaries to converge on Québec City on April 20th in the Red bloc to show the ruling elites that no fence is strong enough to withstand the force of the people when class anger erupts. It’s time for the Revolutionary Anti-Capitalist Offensive!!

IT DIDN’T START IN SEATTLE, IT WON’T END IN QUÉBEC

Revolutionary Anti-Capitalist Offensive Spring 2001”

Sometime in April 2001: Remote Border Crossing, Eastern Maine

Months of scheming, plotting, and planning—and it all boiled down to this one most momentous of moments. I slouched back in my seat, opened my mouth gaping wide, let my tongue hang out just enough to be believable, and generally did my best to look pathetically fast asleep.

We rolled in. “Where you boys headed?” she asked us. I cracked open an eyelid—the curiosity was too much for me to handle. She looked old, friendly, innocent. It was 3 am, and she was alone. Good signs. “Newfoundland ma’am, ski trip ma’am” answered our driver, decked out, as we all were, in his finest yuppie wear. I personally was sporting khaki pants, a Carhartt vest, and sunglasses around the collar of my shirt, despite it being the dead of night—in the middle of the winter—in the great sunless north. I’d seen yuppies in the wild before, and apparently they did these things! A printed-out map of the ski area at which we had made reservations, as well as two pairs of skis in the middle of the car, completed our disguise.

“All US citizens? Any criminal records?” The tension was unbearable. We knew this routine, and these were exactly the questions we hoped to avoid. The entire reason for this somewhat complex operation to enter Canada was that we were the dirty car. As in—the one filled with the problem kids, traveling as one group so as not to compromise anybody in the next shipment of anarchists across the border, all of whom were still legally clean. We weren’t all US citizens, and yes, there were some pretty exciting criminal records among the gang.

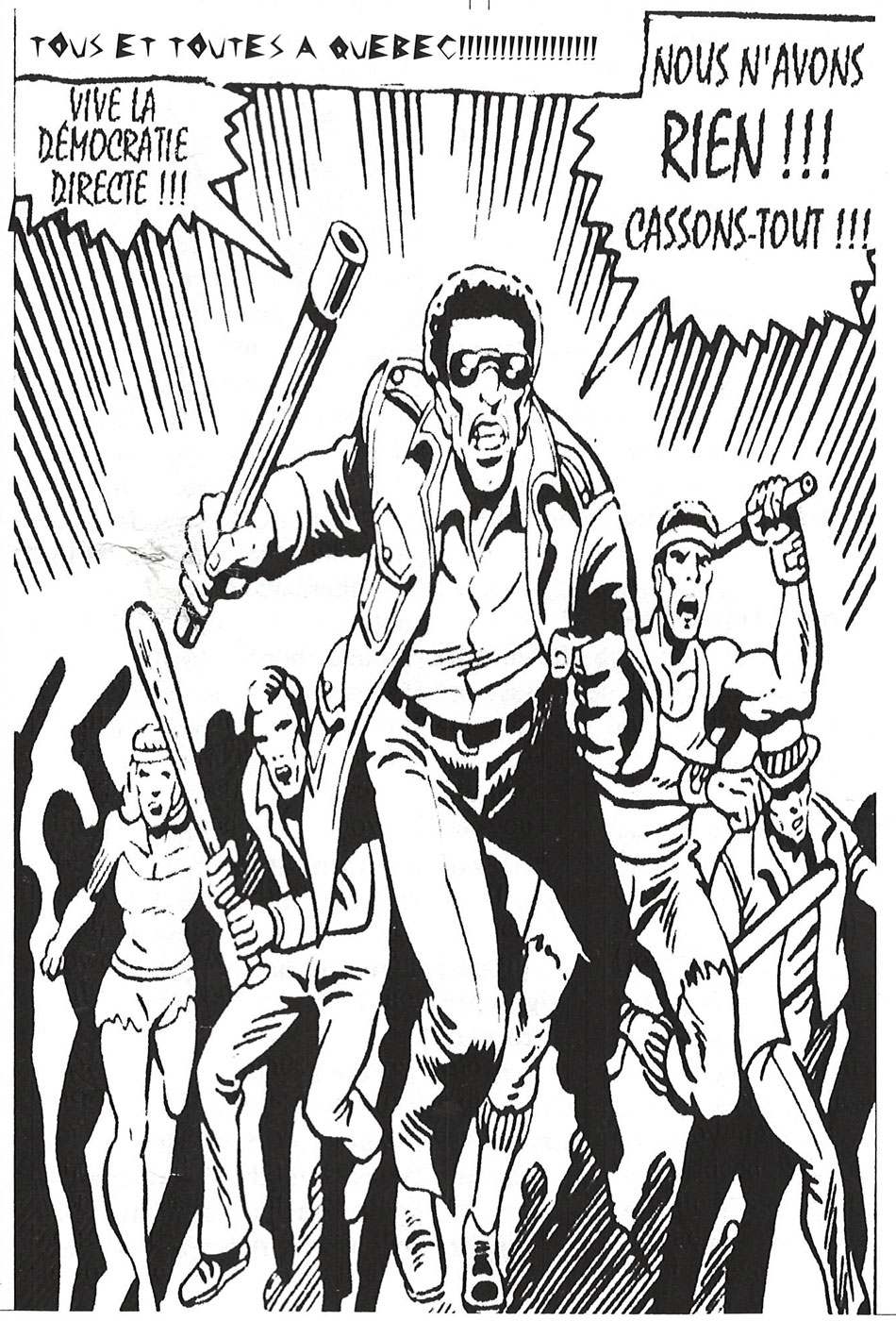

In my personal case, it was even worse. A couple months earlier, on our way to a planning meeting in Montréal, we had been stopped at the border. In finest international drug smuggler style, our car carried its contraband stuffed inside the lining of the car’s doors. Of course, in our case, instead of drugs, we were trafficking the March issue of Barricada. And while the customs officials didn’t find the ones stuffed in the doors, they did manage to find the small stack which some absolute imbecile (possibly myself) had left under the driver’s seat. And this was unfortunate. Because while Barricada was never the subtlest of publications, that particular issue—issue number five—was especially direct. The cover was a full-color fold-out poster of cops on fire, with the headline “Fire and Flames for Capitalism!” Not necessarily the calling card you might want to present at customs and immigration, right? Worse, the last page of the magazine featured an extensive list of creative ways to cross the border into Canada, ending with a graphic of a mob of armed people, blaring: “WE HAVE NOTHING—DESTROY EVERYTHING! EVERYBODY TO QUÉBEC!”

“Yeah, I don’t know how this got here, officer,” I had answered. “Honestly, I just volunteer at a bookstore and they asked us to take these for them. I didn’t even think to look through them, I don’t know anything about politics myself. This is crazy. I’m personally offended by this content and believe you me, I’ll be having some harsh words with the people who gave me these. What’s that you ask? Are we headed to Québec City? No, of course not. We are just young college students on our way to Montréal for the drinking of alcohol.” It was the most unconvincing story I’ve ever tried to sell, and felt almost embarrassed to be pitching it out loud. Which is why I still can’t believe to this day that, despite essentially announcing in writing that the purpose of our visit is how to best organize to burn one of their cities to the ground, those people actually still let us into their country! Of course, they attempted to interrogate us, and lectured us on the virtues of Canada as a democratic country that was interested only in keeping troublemakers out, and made us sign a document stating that we understood we were allowed only to the Montréal area and, if found in Québec City, would be subject to arrest and deportation—which I promptly tossed in the first trash can as soon as we had arrived safely in Québec City. But we made it, that’s the point.

Back to the scene of my second attempt to cross the border, the ski trip. After a brief but agonizing silence, the rest of the car laughed and responded with a pretty confident “No.” I drooled intelligently. What a preposterous concept. Us? Rich, white, yuppie college students, headed to a ski resort in a brand new golden rental car, made possible by the kind financial contribution of an aging radical leftist professor? Could we be criminals or foreigners? Of course not!

“Can I see your ID, please?” This was bad. ID checks we certainly couldn’t stand up to. The whole purpose of this charade was because we had no doubts that, despite being allowed into Canada after the incident with the incendiary reading materials, we had at the very least landed ourselves on a no-entry list and would be denied crossing at summit time. [Indeed, we later learned that many comrades had been turned away at the border for considerably less.] My dreams of days and nights of fire and brimstone on the streets of Québec were slipping through my fingers.

She took the IDs, glanced through them halfheartedly, and started to give them back. One of us had an odd name. She commented on the fact. “Yes ma’am, you see ma’am, my parents are from __ ma’am, and the name is traditional __ ma’am.” This was tragic. He was rambling. I liked him, but I would be forced to kill him as soon as we got out of this place, regardless what direction we ended up going. It’s a golden rule: when telling imaginary tales, say as little as possible while appearing to be a perfectly normal person engaging in conversation. The more you talk, the more room for error. And furthermore, absolutely refrain from saying “ma’am” every damned second word!

Mercifully, he stopped. She started to wave us through, then stopped. “Oh, what about him? He Americun? Arrests?” She was referring to me. I drooled defiantly. Silence ruled the vehicle. Why the hell weren’t any of the idiots I call my comrades opening their mouths? Finally, somebody answered: “No.”

“Should we wake him?” The moment of truth had arrived. If they “woke” me, I would have to answer. If she asked to see my ID, I would have to present a passport, and she would have to run it on the computer, and that would be the end of that. We could go home and watch it all on TV. Or else temptation would draw a bald-faced lie out of me, and we would very possibly spend the summit sitting in a cell, without even so much as the privilege of watching it on TV.

“Nah, let ’im sleep.” I drooled victoriously, an evil grin spreading upon my imaginary internal face. She waved us through. It was there, on that forgotten Maine road, directly on the way to Newfoundland and several hundred miles East of Québec, that we scored the first of what would be a week of many victories. We were safely over the border.

Just Because You’re Paranoid…

The next thing I remember, we were driving into Québec City. We even took the extra effort to drive around the entire city in order to enter it from the North, just in case police were controlling the directions from the US and Western Canada. We really didn’t want to miss this!

We drove past the convergence center in our fancy rental car, with quite a few pairs of eyes intently set on us—they were clearly thinking “Those are obvious undercovers, try to remember their faces, this may be useful to you in the days to come.” (Note to you young ones out there: Never, ever, ever go to the convergence center. They are death traps for the innocent, gullible, and helpless, crawling with surveillance, cops, whackos, and every other danger imaginable.)

I recall our courageous and to this day much-admired driver with gratitude, despite my fears at the border. Not only did we force him to take history’s longest route from Boston to Québec City but… he them immediately undertook the drive back to Boston, only to return with another car full of crazed anarchists a few days later. An unsung hero if ever there was one!

I recall sitting in meetings conspiring with people I’d never met, wearing a ski mask the whole time because you never know who’s there and you can never be too cautious. I refused to attend what turned out to be a pleasant nighttime warm-up demonstration out of fear of pre-emptive arrests, as had occurred at a few previous mass mobilizations. Mainly, I recall staying cooped up in the “safe house” and waiting for the days of action to begin, with a growing sense of paranoia.

I felt like the world’s most wanted fugitive, regardless of the fact that I was guilty of no other crime than fantasizing about smashing glass, panicked cops, tumbling fences, and humiliated and shamed politicians. Well, I guess we were all guilty of some kind of conspiracy and it was probably less than completely normal to be living in a house with enough helmets and hockey sticks to equip several professional ice hockey teams—but those details aside, we were model citizens. I was so paranoid that every time I made the intrepid voyage across the street to the supermarket, I half expected the cashier to take one look at me and order the doors of the store be locked as she called the police, nervously muttering “uhh, we got one here, pretty sure he’s here for the riot”—in French with a strange Québécois accent, of course. No amount of acid or other expensive designer drug shit will get you these delusions.

Now, mind you, this wasn’t the fear of the inexperienced, or what have you. It was the fear of the compulsive troublemaker, sensing himself lucky enough to have arrived at what was, until that point in his life, the biggest pre-scheduled political disturbance he was to have the pleasure and privilege of partaking in. Many others at least as deserving as myself had been turned back at the border, forced to follow the events on TV as a sort of anarchist version of the Super Bowl—but for us, everything was going perfectly. All that was left to do was to wait patiently… and it was killing me!

To be fair, our being safely in Québec City had very little to do with luck and very much to do with the intensive effort, organizing, and planning we had invested into making this mobilization a success. Together with comrades from other cities, we had written up both of the “Revolutionary Anti-Capitalist Offensive” calls, which were then subsequently published in issue 5 of Barricada, signed by an “Autonomous Organizing Collective of Anti-Authoritarians from the Midwest, Northeast, Montréal, and Québec”—with the suspicious disclaimer that we had “received these texts anonymously” and were simply “printing this call and providing space in our publication in order to ensure the success of this initiative.” Never ones for armchair quarterbacking, we had been up to the city several times in the previous months and took an active part in ensuring that the right elements were mobilized to town, that they had the logistical elements necessary for their safe arrival, that once they arrived they would be well cared for and equipped, and—just as importantly—we attempted to provide the political coordination and cohesion necessary to ensure that we could field an effective fighting force on the streets of Québec, not just tactically but also politically.

…Doesn’t Mean They’re Not After You: The Germinal Affair

On April 17, just three days before the start of the summit, François, one of the Québécois comrades, breathlessly entered the house to inform us that six individuals from Montréal were arrested “with an arsenal of smoke grenades, shields and baseball bats that police say were to be used at the summit” as they drove to Québec City. While the arrest of some comrades was unfortunate, a pre-emptive arrest on the way to a summit didn’t seem particularly out of the ordinary at first, even if the loss of a small arsenal of shields, bats, and smoke bombs was an unfortunate setback.

Yet François seemed extraordinarily concerned. Our Québecois friend, temporarily losing his grip on the English language in his agitation, struggled to find the words. “No, no. You’re not understanding. Germinal! It’s the people from Germinal. One of them was a cop!”

Backs arched, heads shot up, and we exchanged urgent looks as we began to understand what he was saying and the implications for us. The “Montréal” part of the “Autonomous Organizing Collective of Anti-Authoritarians from the Midwest, Northeast, Montréal, and Québec” was in fact, among others, comrades from Germinal with whom we had met on more than one occasion. Germinal was a small but politically heterogeneous group.2 As they described themselves in a press release a few days after the arrests, they defined themselves as a “political self-defense movement based on the principle of facing the force of police on equal footing.” In their words, “our struggle has pitted us against the thugs of the state” and “to effectively resist… organized force, it’s necessary to also organize civil self-defense.” This was a sentiment and a spirit we identified with, focused as we were in ensuring that our side arrived at the impending clash with the best possible material as well as political preparations so as to not be mere punching bags for the thugs of the state. It was unsurprising that we had drifted towards each other in the course of preparing for the summit.

Someone said the obvious thing that we were all thinking. “We need to get the fuck out of here, right now!”

Jorge remained silent, assessing the situation. “Who did you say this place belongs to? You said they weren’t political, right?” he asked François.

“Right, it belongs to a non-political friend of a non-political friend.”

“OK, so we’re safe on that side. We entered Canada without our passports or IDs being run, with a car whose plates don’t trace back to any of us, and which is anyways already back in the US. So there are no names to look for or car that can lead them here, either.” He looked at François, then at Cadger, then at me. “Our safety here depends on everybody being honest and admitting mistakes if they made them. Whatever embarrassment you might feel—trust me, that will be better than us all getting picked up because somebody was too ashamed to be honest.”

He continued his comradely but determined interrogation. “Did either of you use your real names during any of these meetings or at the consultas?” He was looking at Cadger and me, as we were the only two Barricada members who had attended the consultas. The consultas were open general assemblies attended by hundreds of activists of all stripes; we had taken advantage of them to hold private meetings with other militant elements. We had made an art of each using a new and wholly unremarkable name at every meeting, mobilization, or city we visited; the only downside being the numerous awkward moments when, in the course of a meeting or event, someone would address one of us by his or her supposed name, and that person would fail to react until the situation became inescapably obvious. “Oh right—right—Joe! Yes, it’s me you’re talking to, because Joe is in fact my name and has been so since I was born.”

Back to the living room in Québec City. “François, besides your affinity group and us, does anybody else know we’re here? Because that’s really the only weak link I can think of.” François shook his head with conviction. Jorge presented his conclusion: “I think we’re safest here. Any comrades’ house will be worse, we definitely can’t check into a hotel, and even just walking down the street exposes us to getting stopped. Finally, if they were going to do a wave of arrests, they would have carried them out simultaneously so we couldn’t scatter and disappear. I know it seems counterintuitive, but I don’t think they’re after us. I think we’re safest here.”

While Cadger and I were basically already halfway out the window, Jorge made some solid points. I looked lovingly at our mountain of helmets, hockey sticks, and pucks and pondered the sad fact that if we were to leave, we would be forced to abandon our arsenal. Combat folklore and misplaced romanticism aside, abandoning our materials would be a serious setback to the larger bloc, as we had stockpiled materials for a good forty or fifty people. We took the necessary precautions, such as setting up a twenty-four-hour watch, and made the political decision that if they came, we would resist in the hopes of creating a standoff that could last long enough for more activists to gather and create a visible conflict. But we chose to stay.

Had we known then what we learned soon after, we would not only have immediately scattered to the four winds, we probably would have proceeded to make our way out of Canada as quickly and discreetly as possible. Our assumption at the time, which seemed reasonable, was that there had probably been an informant in the immediate social vicinity of Germinal—a trusted sympathizer to whom somebody had said too much, leading the cops to a relatively lucky strike.

In fact, the reality was solidly out of a spy novel. While we sometimes underestimated ourselves and the danger we represented to the state, they were deadly serious about us and prepared to invest a lot of funds, time, and energy in trying to neutralize us.

As Mario Bertoncini, one of the arrested Germinal members, explained in an interview a few months later,3 “The police discovered our movement following a tip in November” (of the year 2000). In early December, a 34-page report prepared on the basis of information delivered by a police informant in which it was stated that “a group of leftist and anarchist militants was organizing for demonstrations around the summit (…) with the objective of de-stabilizing it,” marked the beginning of the months long operation.4

After several months of 24-hour surveillance and monitoring all the incoming and outgoing phone calls of the Germinal members known to them, the authorities devised a plan to infiltrate the group. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP, or GRC in French) mounted a joint operation together with the Sûreté du Québec, the provincial police service for Québec, in which they “created a fake transportation company between Montréal and Québec, seeking to employ one of our members.”5 Knowing that Jean-François Dufresne, one of the Germinal members, was looking for work, they proceeded to “post notices (in the area) around his apartment. Jean-François in fact turned out to be the first person to apply for the job,” which offered what was at the time an attractive wage of $75 Canadian dollars per trip. “Jean-François was immediately hired by Andre Viel, a police officer in the RCMP since 1991. Eventually, Alex Boissonneault, another Germinal member, was hired as well. Some time later, the police officer Viel introduced a new ‘employee’: Nicolas Tremblay, RCMP police officer since 1997.”6

The police officers used the repeated long drives between Montréal and Québec, fifteen of them altogether, to gain the trust of their targets. The police infiltration strategy was as much effective as it was classic in the infiltration of radical movements. “First, begin lightly with an employer-employee relationship; proceed to fabricate a false relationship of friendship based on supposed common interests or opinions; finally, develop a bond of camaraderie uniting militants in struggle against a common adversary.”7 In likewise classic infiltrator fashion, the two policemen who eventually became new members of the group were extremely rich in material resources, eager to share them, unusually enthusiastic, and often attempted to push other members of the group to more radical and violent plans.8

Fearing infiltration and at times suspicious of their new “comrades,” Mario explains that they concluded that “there didn’t seem to be any risk, since it was inconceivable that they would have created a business, mobilized numerous vehicles, hired us and invested all this energy just for our little group.” Not only did it turn out to not be inconceivable, but according to a police source, the entire operation ended up costing nearly one million Canadian dollars.

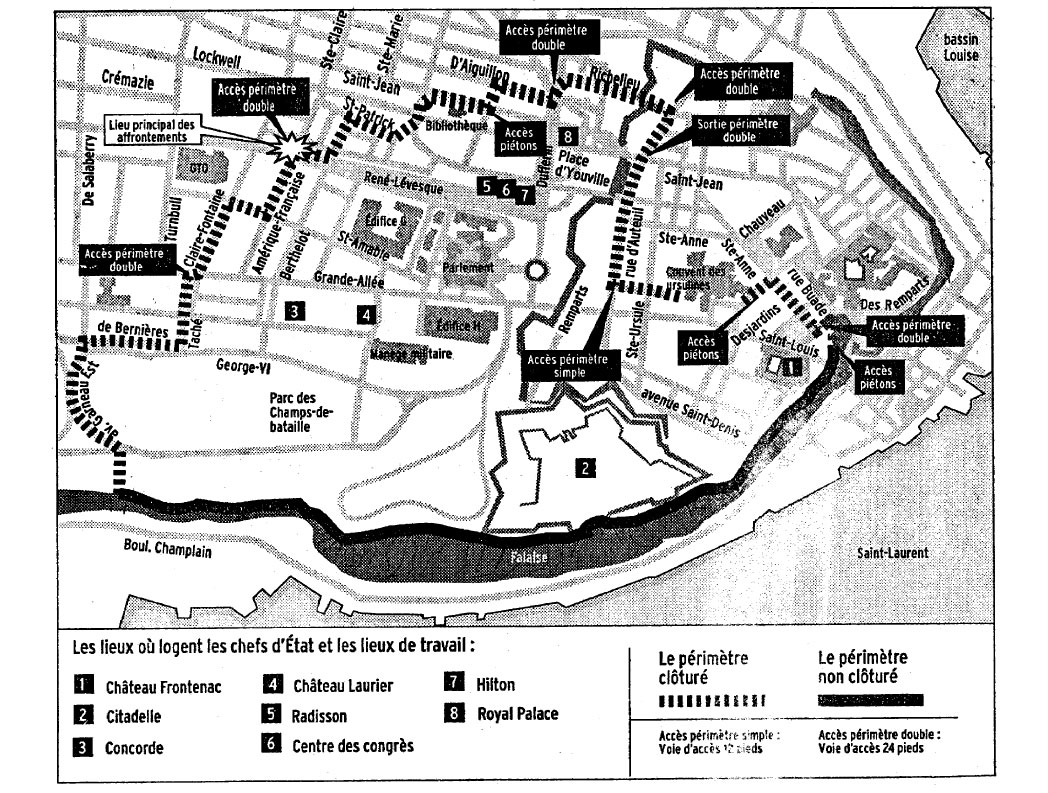

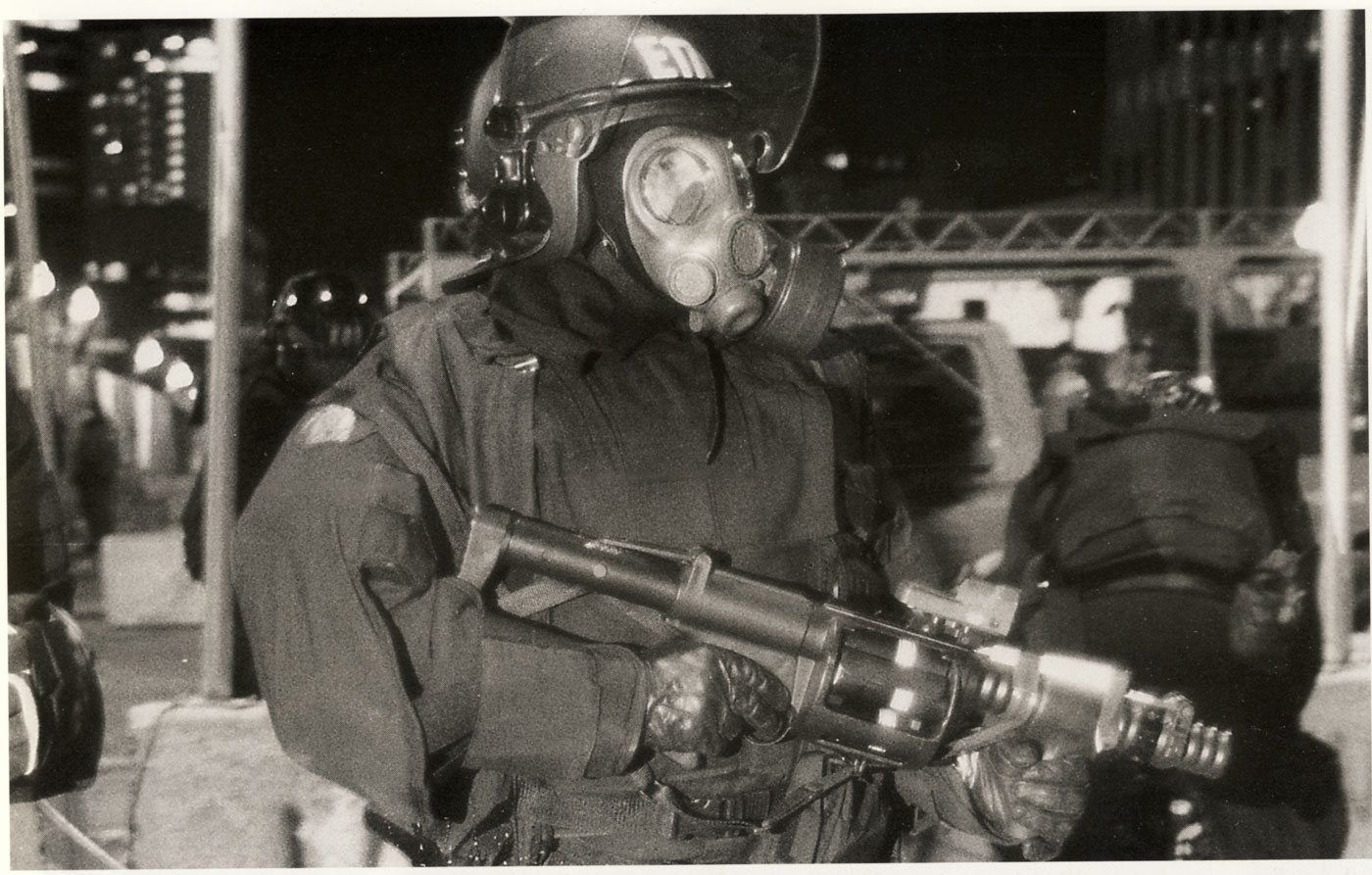

The end result? Seven arrests and charges of “conspiracy to commit mischief that could present a real danger to the lives of people,” “possession of explosives with dangerous intent,” “theft and concealment of military equipment of a value less than $5000,” and a dramatically produced press conference on April 18 in which the police presented the formidable the arsenal of the so-called “Germinal Commando” to the press and general public. The media were all too eager to present the story of dangerous armed anarchists extremists plotting to lay siege to the city of Québec, blaring information about the arrests and their footage from the police press conference on the front pages of all the main newspapers.

According to Le Soleil, the arrested “had at their disposal a formidable military arsenal” and were preparing to “cause serious damage with stolen military materials (…). The activists also had gas masks, slingshots, two bags of steel bearings, homemade shields, baseball bats, motorcycle helmets, chains, a hammer, pliers, and several thousand anti-globalization flyers.”9 The theatrics of state repression were completed by the display, along with the mostly defensive weapons, of assorted dissident literature, “including copies of the anarchist newspaper Le Trouble.”10 While the Journal de Montréal speaks of the “perfect rioter’s kit,” Le Devoir takes the police discourse one step further and writes of “bombs” being found among the Germinal group’s materials.11

We watched the television coverage of the police press conference in concerned silence, and took in the sensationalist newspaper coverage on the morning of April 19. If the plan was to dissuade us, it failed. We were already in this dance, and at this point, had no intentions of abandoning it. If anything, these events strengthened our conviction and drew into even clearer focus the importance of the battle ahead.

On the other hand, if the objective was to turn public opinion against anarchists and militant resistance to the hated fence and the FTAA summit, then… the events of the coming days would prove that they failed, once again.

While two of the arrested members of Germinal were released after a few days of detention, the rest were held in prison for over forty days. In May 2002, they were found guilty, but in a de facto rejection of the state’s attempts to paint them as dangerous terrorists, they were all sentenced to various suspended sentences and hours of community service.

Friday, April 20, Noon: Laval University

Finally, mercifully, the glorious day arrived. After a long night of staring worriedly out the windows, plotting, pointless helmet wearing around the house, and… finally painting the banner we had told every anarchist in North America that the bloc was supposed to converge around, it came time to move out.

Jorge was there, anxious to get his first real taste of action, having been unable to participate in our adventures at the presidential inauguration in Washington, DC in January. He had also had the misfortune to be out of town when we had our “discussion” with the Nazis in Wallingford, Connecticut the previous months. Spatz, now our in-house anarcho-celebrity better known as the Flying Anarchist thanks to his inauguration feats at the Navy memorial, had likewise missed the events in Wallingford and was itching to get back in the fray. Our grizzled veteran of the protests at the World Trade Organization summit in Seattle, Steve, was geared up to relive those days, and Moose, who had also had his fun in DC, was ready to go.

Finally, last but certainly not least, there was Cadger. Cadger had invested as much time and energy as I had in making sure the FTAA summit would not run smoothly. Always a trusted partner in all things related to danger and criminality (and the boring shitwork as well), he was to be my companion for the day. I’m sometimes averse to partnering during actions—which I’m aware is not a positive character trait—but if there is one person I can work with, he’s definitely the one. The whole trusted crew had assembled, the remaining members having arrived late that night. We were ready for the battle to come.

The walk from our home to the starting point of the demonstration was one of those experiences one is sure to never forget. It had all the hallmarks of a surreal dream. There we were, a group of about a dozen (us, plus our local connection), walking down the street on a perfectly sunny and surprisingly warm morning in Québec, dressed in black from head to toe. We carried a neatly folded banner that was extremely heavy. Wrapped up inside it were a good 40 or 50 hockey sticks with the blades sawed off. Two other comrades tried their absurd best to look like ordinary citizens while lugging a bag filled with hockey pucks. There were crowbars, poles, helmets, hammers. You name it, we had it.

As civilians walked by us, I made it a point to smile and nod politely as if we were simply a bunch of young locals out for a morning stroll. This is a common psychological trick I sometimes use while blatantly participating in sketchy activities. If you act like it is the most normal thing in the world while you are doing it, most people will react like it is the most normal thing in the world while watching it. Of course, this tactic only works within the limits of reason and common sense, and we were pushing those to the limit. And just when it seemed this walk would never end—absurdly, we got lost on the way—the university campus appeared on the horizon.

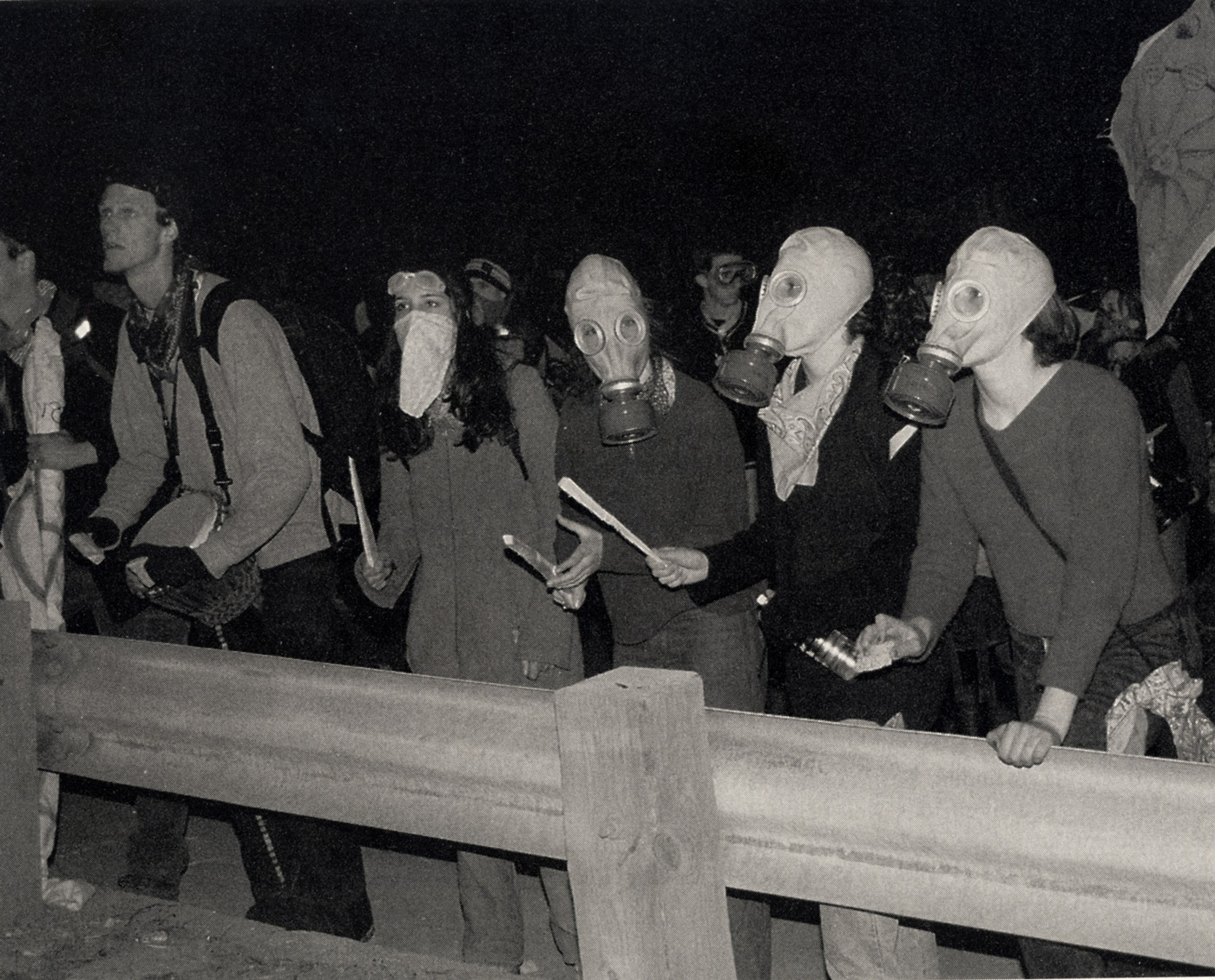

We stood around in the relative safety of the university campus, lost among the gathering black-clad mob. In “Breaking The Barricades: Québec’s Carnival Of Resistance Against Capitalism,” The Northeastern Anarchist described this as “one of the most well-equipped and broadly supported (not to mention, the most gender-diverse) black bloc mobilizations in recent activist history.” I was struck by the irrational fear that the anticipated riot might somehow fail to occur. This fear was especially ridiculous considering that we were now in a group of at least several hundred in which, to quote the aforementioned article,

“many people came prepared with padded body armor, helmets, batons and shields (to counter police attacks); gas masks, vinegar-soaked masks, and heavy gloves (to defend against tear gas); ropes, grappling hooks, and bolt-cutters (to tear down sections of the security fence); and slingshots, hockey pucks, rocks, paint bombs, and Molotov cocktails (to take offensive actions when necessary).”

As we started moving, walking down an avenue empty of shops or officers of the law, this terrible fear that nothing would happen refused to subside. Here I was, among thousands and thousands of demonstrators, a good thousand or so of whom were dressed in black and armed in one way or another, yet I couldn’t stop worrying that nothing would happen. “What if nothing happens?” I asked Cadger. “What if it just doesn’t kick off? What if nobody throws the first stone?”

Wisely, sensing my fear and despair, he answered “Of course it will, of course somebody will throw the first stone.”

“But how can you be so sure?” I pleaded.

“Because, if nobody else does, one of us will. And if we do, the rest of our cluster will too. And then the rest of the crowd will follow.”

The walk into town reminded me of Chairman Mao´s long march. In other words… a death march! We trudged for a solid two hours, wearing helmets and jackets in the unseasonable heat. The road was lined with nothing but trees, small houses, and residential apartments. There was not a cop to be seen anywhere,12 nor anything really worth lashing out at. This scenario did not help to allay my fears. But finally, just as I was expecting victims of heat exhaustion to start dropping from the march, we reached the first symbol of international capitalism on our route: a Shell gas station.

Immediately, individuals surged out of the crowd and hockey pucks glided gracefully through the air, shattering the windows and starting the beautiful music that marks the entrance to the “other reality” of riots and disturbances. The soothing sound melted the anxiety, and the power of numbers and determination roared through the bloc. Not far ahead lay the fence of shame, behind which cowered the rich and powerful of our continent, deciding our fate, trading our resources, and curiously… having forgotten to invite us to the party!

Red, Yellow, Green: The Colors of Resistance?

“A few blocks from the security perimeter, an announcement went over the sound system: “Turn to the left to go to the green zone if you would like to participate in a safe, non-confrontational carnival against capitalism.”

“Breaking The Barricades: Québec’s Carnival Of Resistance Against Capitalism,” The Northeastern Anarchist #2

Our march numbered comfortably in the five digits. Of course, anarchists—whether in bloc or otherwise—were hardly the majority of the demonstrators. The broad spectrum of the anti-globalization movement was represented there. There was the traditional hard left, represented by the entire alphabet soup of authoritarian Marxist organizations, including a surprisingly large and well-equipped contingent of Québécois Maoists. There was a fair amount of older anti-war and pacifist types, whose activism seemed to have found a second wind inside the spectrum of the anti-globalization movement. Among them were some of the more dogmatic types, traditionally of the “peace police” and “parade marshal” variety. Their commitment to pacifism was so authoritarian that some would immediately resort to violence and conspiracy theories to justify attacking anyone involved in property destruction and handing them over to the cops. Finally, there were locals, some politically active, others less so, but who had been drawn there by a combination of anarchist and anti-capitalist outreach work ahead of the summit and several unforced errors on the side of the police and authorities.

The authorities had erected a miles-long “security perimeter” around the convention center. This perimeter fence had come to be known as the “Wall of Shame,” despised by both activists and locals. Intended to be erected almost a full month before the actual start of the summit, the fence significantly impacted the daily lives of the residents of the enclosed area. It also presented anti-globalization activists with a simple and effective messaging opportunity: “Which side are you on?”

“The contrasts could not have been sharper. Closed meetings and secret documents inside; open teach-ins and publicly distributed literature outside. The cynical co-optation of ‘democracy’ via a gratuitous ‘clause’ as a cover for free-floating economic exploitation versus genuine demands for popular control and mutual aid in matters such as economics, ecology, politics, and culture. The raising of glasses for champagne toasts versus the rinsing of eyes from chemical burns.”13

Our message was clear and it resonated with many local communities: They aren’t here for you, and we are not the invading “anarchist hooligans” you should fear. The real invaders of your city, your lives, and your well-being are those who build fences to hide behind an army of fifteen thousands cops while they decide our future.

While the political makeup of the crowd was wildly diverse, there was near consensus on two crucial aspects of the mobilization: anti-capitalism and respect for diversity of tactics. Most everyone agreed that the problem was not just the latest iteration of free trade agreements, but capitalism itself—and that all forms of struggle were valid in that pursuit. Today, those positions might seem self-evident, but at the time, the endorsement of explicitly anti-capitalist and direct-action-based positions by what was essentially a mass movement attested to the galvanizing effect that the Seattle black bloc had in influencing the “anti-globalization” movement as a whole. Much of the credit for the success of the mobilization against the FTAA summit was due to two large anti-capitalist coalitions, the Convergence des Luttes Anti-Capitalistes (Convergence of Anti-Capitalist Struggles) in Montréal and the Comite d’Accueil du Sommet des Ameriques (Summit of the Americas Welcoming Committee) in Québec City.

As Cindy Milstein put it,

“It was a brilliant stroke to stake out a non-reformist posture not only in CLAC’s name but in the very theme for the summit weekend as well: the Carnival against Capitalism. An opposition to capitalism was openly front and center, both during the many months of organizing leading up to April and at the convergence itself.”

Most importantly, from our perspective as anarchists, both organizations upheld an anarchist vision regarding both anti-capitalist struggles and what the world to replace capitalism should look like:

“CLAC/CASA’s short lists of organizational principles (…) included a refusal of hierarchy, authoritarianism, and patriarchy, along with the proactive assertion of such values as decentralization and direct democracy.”

Together with a vocal and vibrant rejection of capitalism steeped in anti-authoritarianism, both CLAC and CASA boldly and unequivocally embraced the concept of diversity of tactics. This was particularly effective in the buildup to the summit in defusing the eternal movement debates about “violence” and stifling media narratives dividing demonstrators into “good protestors” and “bad protestors.” Just as importantly, CLAC and CASA adopted the “Prague model,” which had been used with great success just a few months earlier by demonstrators opposing the summit of the International Monetary Fund in the Czech Republic. By implementing a color-coded and geographically separate action concept (red for high-risk actions, yellow for non-violent direct actions involving risk of arrest, and green for actions intended to involve little risk of arrest), organizers were able to designate clearly-defined spaces for people with widely varying tactical preferences and degrees of risk tolerance. This maximized mobilization by “making everyone comfortable setting their own level of involvement and risk.”14

The diversity of tactics stance succeeded in creating what Cindy Milstein called15 a “welcoming space for those many more anti-authoritarians who perceive themselves as less militant. It widened the margins not of militancy, in other words, but of what it means to reject capitalism as an anti-authoritarian.” In practice, “what the diversity of tactics principle translated into was a diversity of people.”

A few blocks before we reached the hated fence, the sound system announced: “Turn to the left to go to the green zone if you would like to participate in a safe, non-confrontational carnival against capitalism.” Hundreds, maybe thousands, broke off from the march to head into the neighborhood of St. Jean-Baptiste, a working-class neighborhood located in the urban core of Québec City, whose residents had been afflicted by the security perimeter, which ran right through the heart of their community. According to Nicolas Phebus, local member of the Northeastern Federation of Anarcho-Communists [NEFAC] and a member of the neighborhood’s Comité Populaire, “the ‘green zone’ on Saint-Jean was a smashing success.”16 This was made possible by the deep ties between local anarchists and the community.

“Years of involvement in the neighborhood, working around various issues with all kinds of people—single moms, working poor, artists, youths, merchants, etc.—proved to be essential. In less than two weeks, we mobilized a new group to organize our ‘green zone’ activities. The response was inspiring: dozens of people took it upon themselves to organize and staff a free food table, an infoshop, a place for kids, different musical events, and so on. On the other hand, we were able to produce a special 16-page issue of the Comité Populaire’s newspaper and distribute 9000 copies of it door-to-door the weekend before the Summit. In this newspaper, we tried to explain everything we thought was important to understand the opposition to the Summit. We had articles explaining ‘diversity of tactics’ and the system of three color zones, the non-reformist approach, the links between globalization and welfare reform, the Black Bloc, and so on. And, of course, a front-page article urging people to take to the streets and ‘occupy the neighborhood.’

“Thousands of locals showed up, many feeling so safe they even came with their kids. It was also used by at least three different affinity groups to carry non-violent symbolic actions (which probably wouldn’t have happened otherwise). (…) This said, we did make a few compromises while organizing it. The biggest is that we felt that, as organizers, we had a responsibility to do whatever was possible to ensure that it was a safe place for everyone. Although we knew that in reality, this wouldn’t necessarily make the place any safer, we did communicate to the police that this was a ‘green zone’ where trouble was not expected. We didn’t ask for a permit, but they gave us one anyway. We also organized a ‘security team,’ which scouted the whole city to know where the riot squads were all day. One compromise was that, although it was an anti-capitalist day of actions, we did collaborate with the merchants on the street and tried to ensure their collaboration. This way, many boarded storefronts became free expression billboards. The action wasn’t ‘pure,’ but we think all of it was worth the price.”

-“Did We ‘Radicalize This’? An Insider’s Look At The Québec Protests,” The Northeastern Anarchist #2

Back on the Boulevard René-Lévesque, the voice on the sound system continued: “For those of you who wish to continue the fight, the fence is straight ahead!”17

This was our cue.

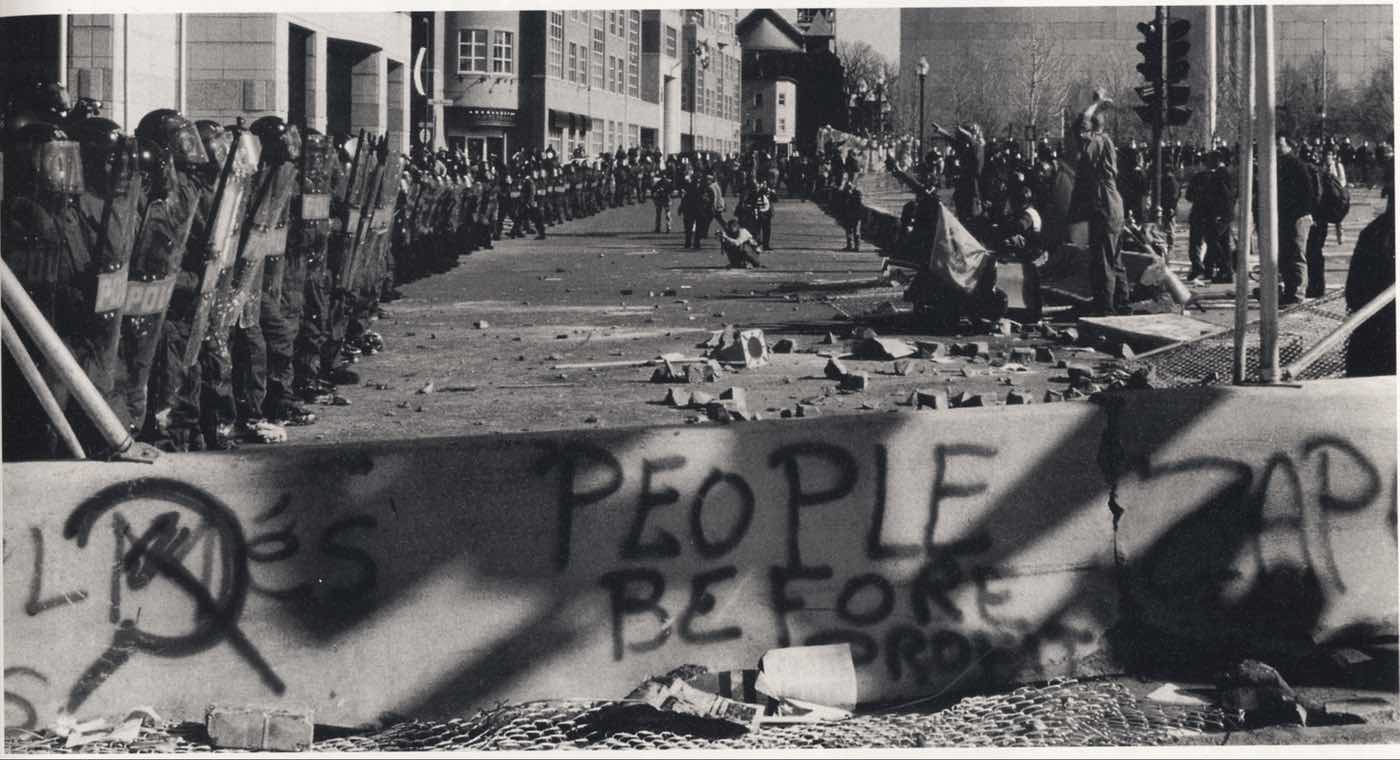

Friday, April 20, 2001, approximately 3 pm. Boulevard René-Lévesque

“Thousands continued on towards the fence, touching off the first of the weekend’s protracted street battles.”

“Breaking The Barricades: Québec’s Carnival Of Resistance Against Capitalism,” The Northeastern Anarchist #2.

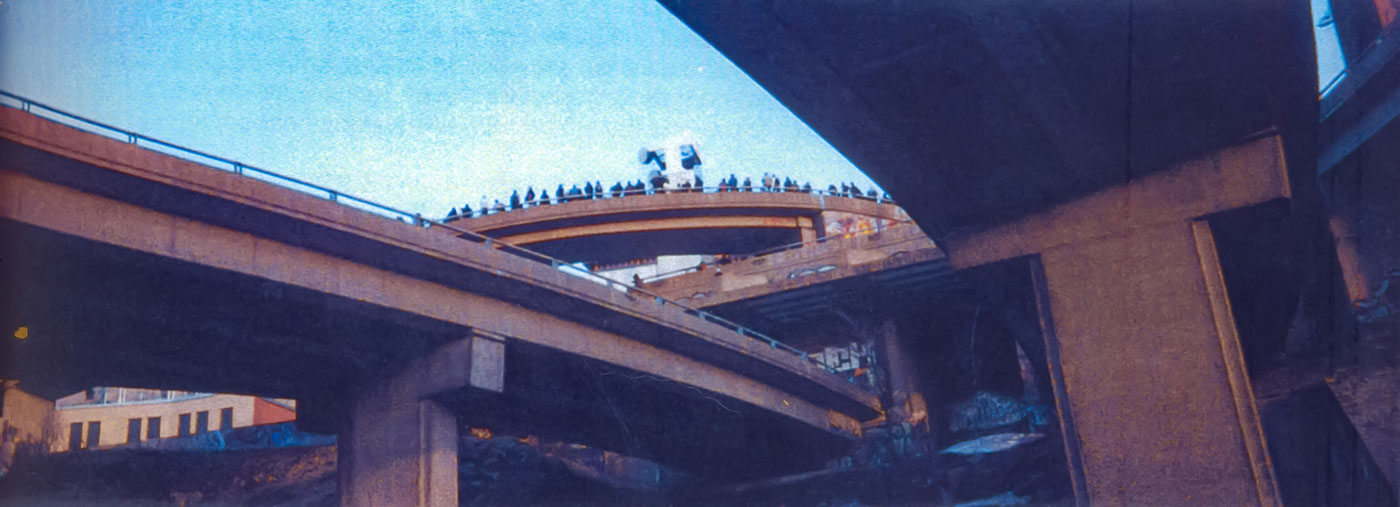

Québec City is divided into an upper town and a lower town, separated by steep cliffs connected in some places by winding roads and in others by steep staircases literally referred to by locals as “neck breakers.” The lower town, one of the continent’s oldest remaining European settlements, still boasts a distinctly European atmosphere: a fortified old town and stone buildings on winding streets lined with shops and restaurants.

But we had reached the upper town. To be precise, we were on the Boulevard René-Lévesque, one of Québec City’s main arteries, a comfortable three or four lanes wide in both directions. As we advanced down the boulevard into the city, we were surrounded by concrete high rises and the drab scenery of downtown North America.

In front of us, not 100 feet away, was a sight that some of the less optimistic of us thought we might never lay our eyes on. Twelve feet of rebar cemented in concrete, glittering in the sun, cutting across the entire length of the boulevard: the “Wall of Shame.” Behind it lay the congress center where the Summit of the Americas was being held. Many participants in the mobilization had feared that we would be attacked and dispersed before we got anywhere near the wall. But for some reason—fear of our movement, or tactical error, or excess confidence in the effectiveness of their barrier—the guardians of state and capital were all concentrated on the opposite side of the fence. Corporate media cameras were lined up at stage right on our side of the fence; as we approached, some comrades promptly began to destroy the cameras and vehicles, calmly citing instances of biased coverage to explain their actions as they spray-painted lenses and stomped in windshields.

The black bloc surged to the front; comrades attached ropes and grappling hooks to the fence. Teamwork and coordination came naturally as hundreds of people pulled on the ropes attached to the fence while others rocked it back and forth strategically. The fence that they said could stop a vehicle traveling at 90 miles per hour couldn’t withstand the force of our movement for five minutes.

I can affirm with all the conviction in my heart that the scenes that followed were some of the most beautiful moments that I have ever had the good fortune to experience, moments blessed with a singular feeling of power and liberation. The sublime instant when the logic that is force-fed to us from birth—for example, the idea that streets are for cars, or that cops are for obeying—ceases to apply. At such moments, all other concerns evaporate, the body becomes seemingly invincible, physical pain no more than a small nuisance, and desire and conviction shape realities. It is the moment when ordinary rebels filled with rage and hope can act in accordance with the urgency of their yearning, when adrenaline courses through the veins and nothing else matters beyond the experience at hand.

I felt it in that moment and I can’t deny it now. Battle makes me happy. It makes me feel alive. The acrid smell of tear gas makes me feel nostalgic. I can’t put vinegar on my salad without thinking of the relief it often afforded me from the blinding effects of chemical warfare.

Yet I will argue until I turn blue in the face with anyone who claims that this is because I enjoy violence.

“The truly violent are those who prepare for the summit by accumulating tear gas, plastic bullets, and pepper spray. Those who enact laws and measures that will put hundreds of thousands of poor in the street, those who let pharmaceutical corporations make billions on sickness, causing the death of millions of people, those who are copyrighting life and creating dependence and hunger. In a word, those who put their profits before our lives.”

“Anarchists: You Only See Them When You Fear Them,” an article in a NEFAC tabloid distributed during the 2001 FTAA Summit

Battle against the state is the fulfillment of my convictions. It is the realization, however fleetingly, of my ideas. It is completely natural to take pride and pleasure in those moments and those acts. It is with exhilaration and joy that I enter into battle for my beliefs. That moment represents, at the very least, an opportunity to advance my ideas and to combat the forces that are diametrically opposed to them. In the spaces we create, be they permanent structures of dual power or temporary liberated zones in which we beat back the forces of the state, we catch a glimpse of the world that I aspire to help build and one day live in. This is joyous work. How could we help but wear broad smiles under our masks?

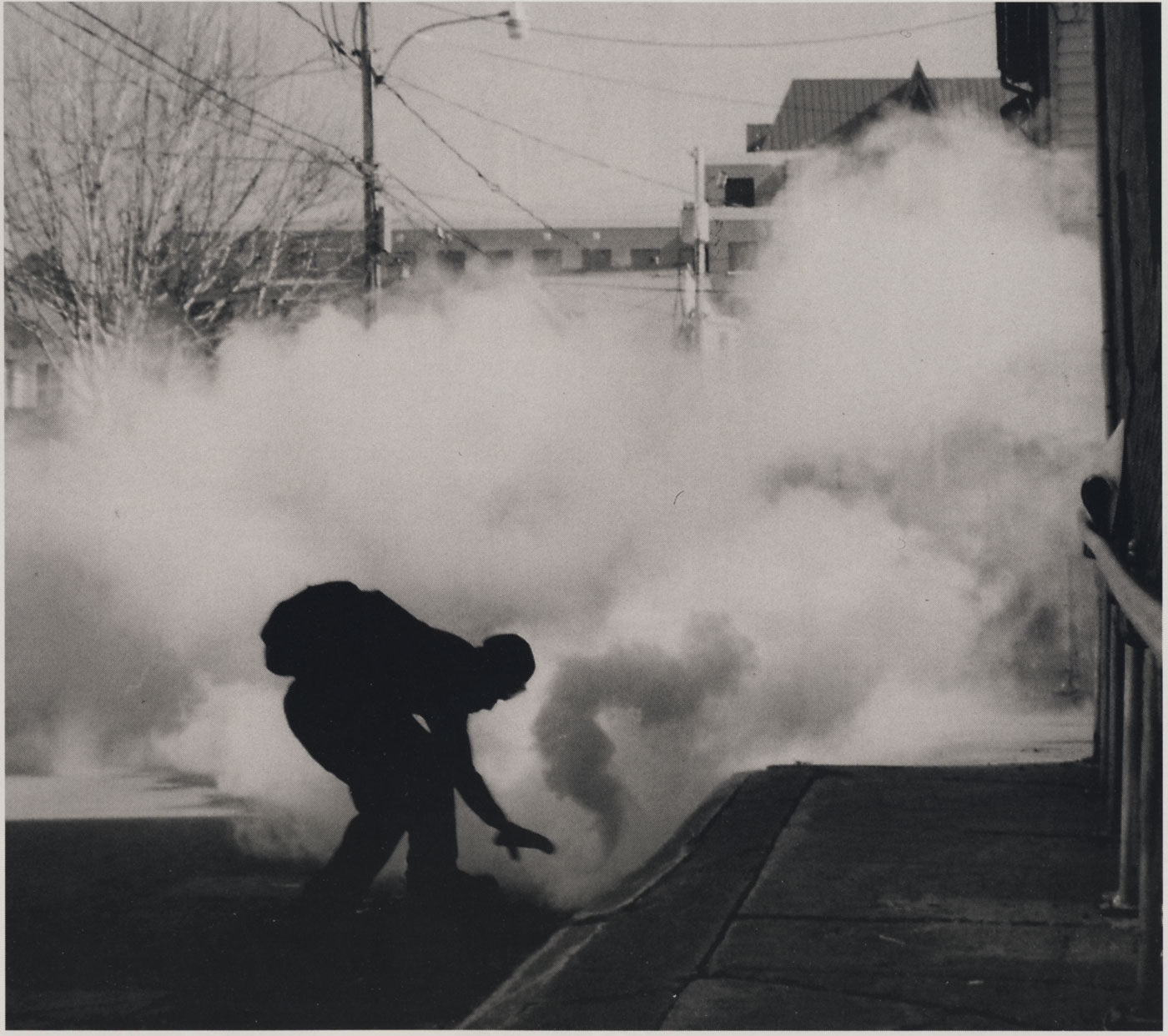

Risks were forgotten, consequences deemed irrelevant. This was what enabled us to create the beautiful and unforgettable scenes of ordinary people becoming fire-hurling superheroes, of rather small people hurling enormous chunks of pavement with surprising ease, of red and black flags flying high amid clouds of tear gas. This was what enabled us to topple the fence that, according to the authorities, could “stop a car traveling 90 miles per hour.” This was what put us face to face with the riot police.

Next, those in the front swarmed into the “red zone,” throwing ourselves directly at the lines of riot police, who retreated slowly, surprised by our conviction and determination. Small groups charged them with metal barricades while others continued the aerial bombardment involving chunks of cement, golf balls, and hockey pucks. It even included a few teddy bears, launched by way of a rolling catapult!18 I was overcome by “riot tunnel vision,” in which the only direction to look is forward, and threw myself at the cops. Barricades flew, arms and legs swung, and I picked a tear gas shooter to concentrate on. Unfortunately for me, at the same instant that my hockey stick swung through the air towards his body, the line of cops parted directly to his left and another officer armed with a tear gas shooter appeared behind them. The second officer pointed directly at my chest and fired. I barely had time to grimace.

First, the air left my body. Immediately after, a cloud of white powder exploded onto my jacket, flying straight up into my face. The $2 goggles I was wearing and my vinegar-drenched ski mask allowed me to take note of the situation around me in the instant before I became completely blind.

In my mind, the toppling of the fence was to be followed by a mass invasion of the “red zone.” This was the mission I had committed myself to. I had taken for granted that others were on the same page. Sadly, the reality was quite different.

I looked back and beheld a scene reminiscent of a Roman gladiator battle. The deafening roar of the cheering crowd was coming from a mass of people lined up a safe distance behind the fallen front section of the fence, or else—still worse—lined like spectators at a marathon behind the still standing sections of fence and on the sides of the street. The number of people who had actually crossed the (now imaginary) line between “our” zone and “their” zone seemed to be a few dozen, perhaps fifty at most.

Why didn’t more people cross the fence into the “security zone” after the black bloc pulled down the fence on the afternoon of April 20, 2001?

In the meetings ahead of April 20, there had been fierce debates about whether to march on the fence or to go elsewhere in the city. Some organizers, including Québec City locals, believed that the police would make it impossible to reach the fence. In fact, the march was able to reach the fence and tear it down almost without incident, and it took the police several minutes to mobilize after it fell. Yet once the fence came down, most people stopped there, as if paralyzed, giving the police plenty of time to regain the initiative. Not being able to imagine that they could succeed in reaching and toppling the fence, most participants had simply not asked themselves what they would do if they got that far, so they failed to press their advantage.

We’ll never know what would have happened if everyone had confidently crossed the toppled fence into the security zone together. But this underscores the importance of visualizing the possibility of success in advance, in order to be prepared to take advantage of it. The first time a tactic is employed, if it fails, it is often because those employing it do not take it far enough; after that, when a tactic fails, it is usually because those employing it have lost the element of surprise. We should always prepare for the best-case scenario as well as the worst. Sometimes we only get one chance.

-Interview with a CrimethInc. agent present at the demonstrations, April 2021

Being on our own in the front was not our only problem. Around this time, some misguided genius threw a Molotov from within the crowd, almost hitting one of our own. Another person did more or less the same, almost grazing my helmeted head, sending a rather unpleasant whoosh of heat in through the side of my helmet. At the same time, a few other people had placed themselves smack in the middle of the conflict area in a non-violent sitting protest, creating a significant risk to themselves.

This text is clearly an account of a great deal of rioting and the like. But I want it to be clear that I have nothing against pacifists, and by no means do I view confrontational action as the only way to achieve revolutionary social change. Far from it. It is but one tool in what must be a wide array of strategies and tactics. Further, confrontational actions can even be counterproductive if they are not deployed in tandem with the day-to-day work of building structures of popular power and resistance. There is a time and place for everything, and hypocritical as it may sound in this context, it is important not to prioritize the more glamorous aspects of our work over the others. A wide and diverse movement with room for all to participate in it in the ways they see fit is the only kind of movement that can succeed.

That disclaimer now behind us, authoritarian and ultra-ideological pacifists are also not to my liking. Dogmatists who believe they have the right to impose their tactical and philosophical concepts on others have no place in a healthy anti-authoritarian movement. Particularly vile are those who believe that the heat of battle is a good time to make their point. Those who interfere during actions, who try to grab militants during fights, who put out fires in banks (fires set with much love and care!) render tasks that already involve risk much more dangerous, putting others at additional risk as well as themselves. Among ourselves, we made the stern decision that those who purposefully interfered during actions, exposing us to risk of arrest and injury, were essentially doing the job of the police. For that reason, we were prepared to give them the same treatment that we would normally reserve only for the repressive agents of the state.

Unfortunately, I had bigger problems than the pacifists sitting down in the middle of the battle zone. By this point, I was damned near blind from the tear gas wafting up from my jacket. I staggered back out of the gladiator cage and into the crowd. In the nick of time, too, because shortly after, I could no longer open my eyes, not for the life of me. Blind as a bat in the middle of a battle. I don’t recommend it!

Fortunately, one of the many golden-souled activist medics came to my assistance. “OK, just open your eyes,” she said, as if she was asking me to do the simplest task imaginable.

I pleaded: “I can’t, I can’t, there’s no way.”

Through my blindness, I sensed her looking at me with pity. I could see it in her voice. There wasn’t much doubt in my mind that I wouldn’t like what she would say next. “Don’t be afraid, it’s OK, just open your eyes,” she encouraged gently.

Grateful as I was, I believe my thoughts were something to the effect of What the hell is wrong with you? Here I am blind in a riot and you want to talk to me about abstract philosophical concepts like fear. Don’t you get it, I’m quite simply physically incapable of opening them.

Thinking it unwise to say that out loud to her, but not knowing how to express the problem more diplomatically, I stammered, whimpering something incomprehensible akin to the sounds of a frightened puppy. I sighed internally and braced myself for the next round of condolences and pity. Finally regaining my composure, I blurted out, “No, you don’t get it. I am not capable of opening my eyes, you need to grab them with your fingers, open them, and squirt whatever magic potion you intend to squirt in them.”

Aside from the sounds of crashing objects, diverse screams and yells, and tear gas canisters flying overhead, nothing much happened. Finally, she said something again. It wasn’t good. “Yeah, the powder from your jacket is starting to get to me as well. I can’t see very well either, we need to get somebody else to take care of you.” She thrust me in some direction—I was still blind, myself—and eventually into someone else’s hands. Thankfully, the next person wasted no time: they pried my eyes open, squirted me with something, dragged me away from the action, and sternly told me to stay put for a few minutes. It was like being a small child on time-out, but they were clearly the voice of reason in the situation.

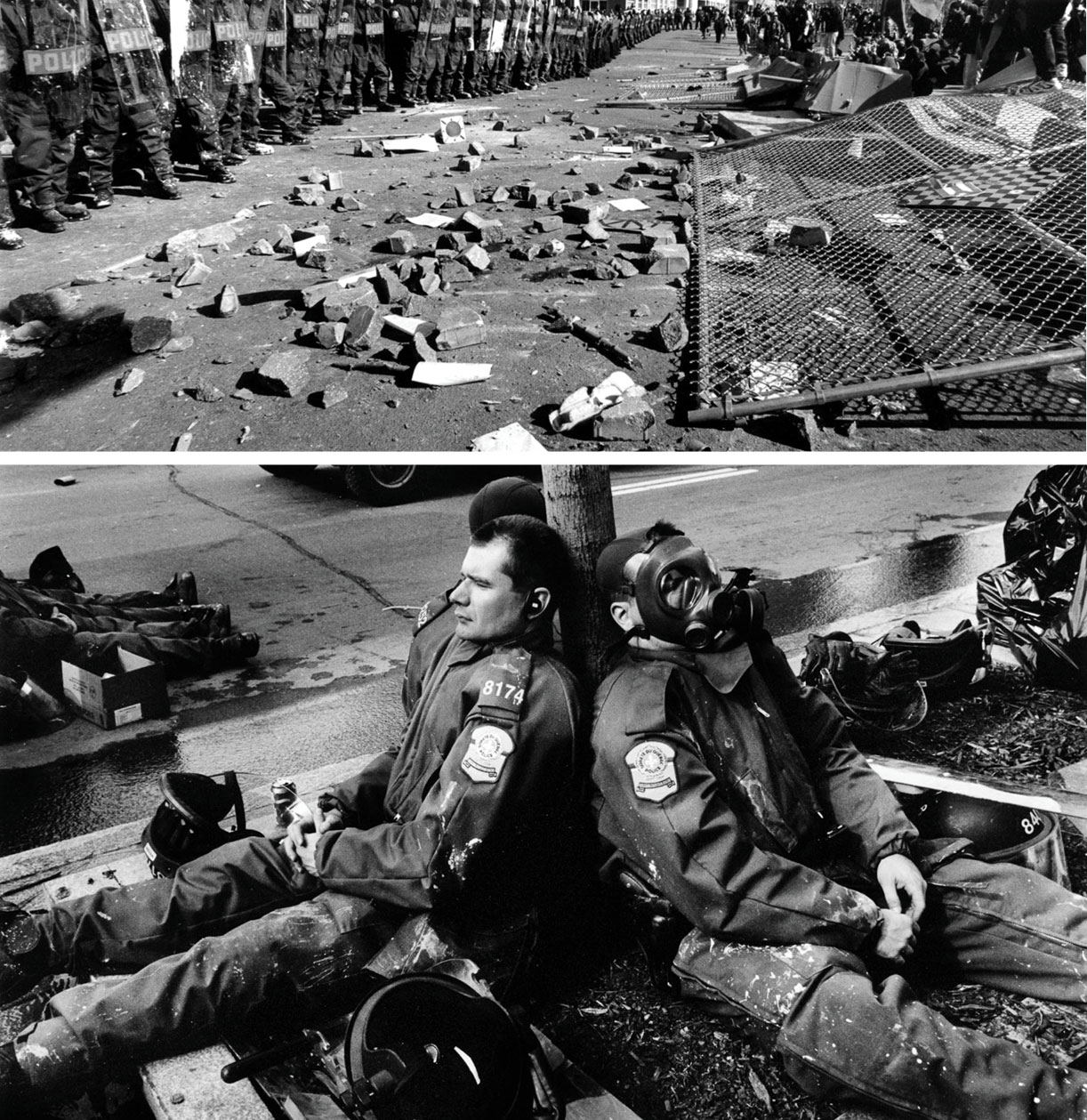

Sitting there, on a relatively comfortable grassy hill, taking in the panoramic view of the action while enjoying the bitter smell and sensation of tear-gas-drenched air, my eyesight slowly returned to normal, permitting me a welcome opportunity to assess the general situation and plan my next steps. The riot cops, having noticed that the crowd would not surge forward and eat them alive, had re-organized themselves and begun slowly advancing.

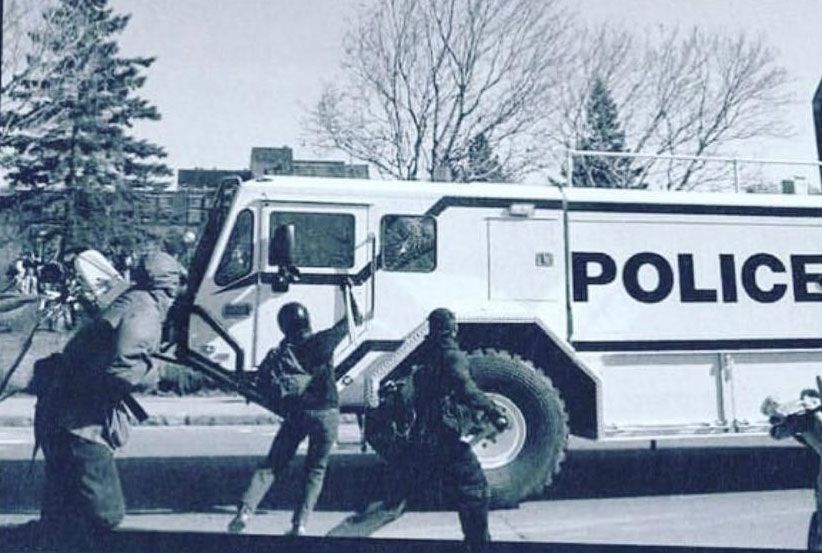

Next, the police sent their brand-new ultra-expensive toy, a water cannon truck, charging in from behind the crowd into a mass of black bloc anarchists. Apparently, the user’s manual didn’t explain to them that water cannons are best used from behind the safety of police lines in order to keep crowds at a distance. Unfazed, we promptly tabled the turns and charged the water cannon! Great was our surprise when, in one of the summit’s most iconic David-versus-Goliath scenes, a lone anarchist approached the driver’s window and successfully smashed it in with nothing more than a wooden hockey stick. The water cannon drove off, not to be seen again that day.

Meanwhile, the cops had figured out that their tear gas canisters were most effective when they lobbed them into the middle and back of the crowd rather than aiming at the chests of those in front. Using this strategy, they had managed to split the crowd into smaller and smaller clusters, creating a fair bit of panic as people retreated from clouds of gas only to find more clouds of gas further behind. It was clear that we had lost the first engagement. We had begun with the element of surprise, but once we lost it, it was impossible to reorganize our forces in that atmosphere. Slowly, sure enough, the fighting died down, as people were pushed into the intersecting streets, towards the direction of the cliffs.

I soon drifted in that same direction with the others, and it was not long before I was lounging comfortably on the steps of some building, helmet and hockey stick at my side, enjoying a warm soup provided free of charge by one of the many activist support groups and pondering the perfectly sunny day, with nary a cloud in the sky. It was a pleasant interlude of calm, chatting with friends and comrades from far-away cities and wondering what the rest of the day would bring.

Play Stupid Games, Win Stupid Prizes

So there I was. I had long since lost both my affinity group and Cadger, “riot tunnel vision” providing me with a strong sense of direction and making me acutely aware of my surroundings while also causing me to forget about anyone who did not pose an immediate threat to me. Like I said, I could be a bit averse to committing to run with a crew during actions. I trust my own judgment and fear being held back by the sheep mentality of militant spectators, a particularly North American phenomenon, at least at the time. Also, a lot of us Barricada kids were pretty well networked, thanks to our roles with the magazine, the federation, in mobilizations, and within anti-fascist circles, and this enabled us to “affinity group hop” fairly safely even in the midst of actions, since we could often find at least one person we could identify and who could vouch for us.

So it was that about four hours after the previously described events, I found myself standing around alone on the same avenue where the fence had been. Our side had lost about a hundred meters to the advancing police line. The situation reminded me of a typical drunken college riot or chaos punk riot. The cops stood there, not doing much of anything aside from firing the occasional tear gas canister, and people on our side played their role in the spectacle as well, throwing the occasional stone or beer bottle.

I, too, threw a stone. It was a stupid, futile act. There wasn’t even any kind of significant cover of people from which to do it or into which I could retreat. I really was playing “drunken punk aimlessly throws rock,” although I was neither drunk, nor a punk, and definitely should have known better. This isn’t to argue that there always has to be a strategic end to an action—it might be enough for it to be an expression of personal rage or a way to develop confidence in one’s abilities. But in this case, what I did was just plain dumb, and I can picture the cop on the other side concluding “Yeah, I think I’ll just shoot the jackass in the helmet who’s standing there alone after lobbing a stone at us.” As the old adage goes: play stupid games, win stupid prizes.

Suddenly, I felt an incredibly painful blunt force impact on my upper thigh. At first, I assumed that a baseball bat had hit me out of nowhere. My leg gave way and I fell to the ground. As medics swarmed around me and an affinity group with shields and helmets rushed in to give them cover, it dawned on me that what had taken me down was not a bat but a plastic bullet. Not a rubber bullet, mind you—a plastic bullet. These are much wider, which is why I didn’t associate the impact pain with what one might expect from a rubber bullet.

Fortunately for me, I once again managed to straddle the fine line between learning a painful lesson and suffering lifelong consequences. I had been shot in the thigh. The upper thigh. The inner upper thigh. Do you see where I’m going with this? Maybe three or four inches from my groin. Judging from the explosion of black, red, and blue bruising that I sported on the entire circumference of my thigh for well over a month, I’m confident that had the shot hit my groin, it would have meant hospitalization at the least.

As it turned out, the medical treatment I received was somewhat different. “Open your mouth, open your mouth,” one of the medics commanded. As I pulled up my mask and complied, one of them stuck something under my tongue. I assumed it would be some kind of medicine, a painkiller of some sort—but being the curious type, I asked what it was. “Vegan chocolate—to help keep you calm.” This may not have been the intended medicinal effect, but it did make me laugh, which temporarily distracted me from the blinding pain.

One of the formless, trash-bag wearing, helmeted, goggle-sporting, shield-wielding creatures that were protecting us turned around and asked if I could walk. This was an excellent and rather terrifying question. Honestly, I wasn’t particularly eager to find out. In the cartoons, you don’t start falling until you notice there is no ground below you; by the same impeccable logic, you aren’t actually injured until you try to use the affected part of your body and it fails to comply. Having been seriously injured once, twice, or perhaps a dozen times, I know this to be undeniably true. As long as could I lie there peacefully enjoying my vegan chocolate, I would be perfectly fine, aside from the pain, and wouldn’t have to confront the possibility that my leg was broken.

Reluctantly, though, I began to get up, since—not actually being a drunken punk or college kid—how long could I lie on the ground in the middle of the street for before it became unseemly?

Fifteen minutes later, I was off the streets and in somebody’s apartment. Two of the previously formless masked and shielded creatures were caring for me; without their gear, they were revealed to be friendly-looking young people. It was the same two who had successfully peeled me off the pavement; despite my insistence that I was fine, they were adamant abut taking me back to their place for a short break to make certain that I wasn’t seriously injured. Going home with strangers you’ve just met and whose names you don’t even know? Questionable even under normal circumstances. Definitely not best practice when playing “lone injured rioter in foreign country.” But the alternative of limping around alone, possibly grievously injured and soon unable to walk, didn’t seem much better. If they were cops, then they were the best-disguised infiltrators I could imagine—they had earned the right to arrest me.

So there we were. John, as we’ll call him though I never knew any of their names, was icing my inner thigh in what I can only describe as an unexpectedly and uncomfortably intimate moment. The other, let’s say Megan, was providing me with painkillers in the form of drugs apparently even more powerful than vegan chocolate. She seemed to have some sort of medical training. I was receiving first-rate, free-of-charge, personalized medical attention, courtesy of one of the world’s finest insurance policies: anarchist solidarity and mutual aid.

Megan gave me her prognosis: “You got very, very lucky. Just a little further towards the middle and you would be in an ambulance or emergency room right now. But as it is, it’s just a really bad contusion.”

“Can I keep…?”

“It’ll probably hurt like hell, but you’re fine to keep going. Or you can stay here if you want, that’s fine too, but we’re going to head back out in a few minutes. Where you from?” she asked me.

Usually I would hesitate, or respond with the go-to lie, “Springfield.” But I was feeling comfortable in the hands of those strangers. I was lying on a sofa, being cared for and fed by street fighters who had cast off their armor and weapons— a small stack of shields, helmets, and slingshots sat by the entrance—to reveal the friendly and caring personalities of unknown comrades. In a moment of rare candor, I responded honestly. “Boston.”

Megan raised her eyebrows. “Do you know the Barricada kids?” I shouldn’t have, but I responded honestly again. “Ummm, kind of. I’m in the collective.” As it turned out, they were familiar with our fine publication.

For a few minutes, we forgot that a battle was raging outside. They told me that they were from Prince Edward Island, a place I have to say I didn’t know existed and which honestly sounded made up. As we spoke, I was amazed at the extent to which although we came from places that were geographically and culturally distant, the anarchist idea—the belief in the principles of solidarity and mutual aid, in class over country—could make comrades of us in a matter of minutes, even in the most adverse conditions.

In that apartment, thanks to a random collective of kids from some far off place I hadn’t even heard of, I was given a practical lesson in an important concept that I had failed to grasp throughout much of my youth. Every fighter depends on a network of support and solidarity, just like any healthy network of support and solidarity needs its fighters. But it isn’t enough to say that there must be a network of support and solidarity behind every fighter—there is no “behind” and no “in front.” Rather, both are equally crucial positions on different fronts of struggle, and everywhere is a frontline. Over the course of the weekend, I learned that the kids from Prince Edward Island were well-equipped, fearless, and militant. Yet most importantly, they showed me that every fighter should ideally be much more than a fighter, and we should never let the role of combatant take over the entirety of who we are.

First Interlude: Friday, April 20, 2001, Late Evening: Seattle, Washington. USA

That evening, FBI agents “raided the offices of the Independent Media Center in downtown Seattle, seizing computer-log records, according to federal sources.”19

Just a few hours earlier, in Québec City, a group of intrepid anarchists had broken into a police vehicle that was either unwisely parked or abandoned by fleeing officers. They liberated shields, helmets, communications equipment, and—most importantly—a binder full of documents. Thinking and reading quickly, they rapidly determined that those particular documents deserved to be shared. They headed to what we can only assume was a safe location with anonymous internet access and logged on to Indymedia—the activist Twitter of the anti-globalization era.

As the Seattle Post-Intelligencer later reported, “Security plans intended to protect Western leaders attending a trade summit in Québec City were stolen from a car there over the weekend and posted, hours later, on a Seattle-based Web site.”20 The wording is deceiving, giving the impression that the uploaded documents, posted on Seattle Indymedia, had to do with protecting “Western leaders” from assassination attempts or the like. In fact, the documents were primarily focused on crowd control strategies and contingencies to be employed against anti-globalization demonstrators—for example, which directions to push unruly crowds, where to call police back up from depending on the location of disturbances, and so forth.

Most importantly for us, the documents included a list of “high risk” individuals and groups to be monitored and targeted, and—it’s safe to assume—to be arrested if identified. It’s not necessarily the world’s longest list. If we had seen it before leaving the house on Saturday morning, one particular line would have caught our attention: “Unnamed individuals from the Barricada Collective.”21

But we didn’t see, just as we were blissfully unaware at the time that a cop had infiltrated NEFAC, as well. As we would later learn in the Coalition Against Repression and Police Abuse’s “The Germinal Affair: The Art of Infiltrating and Manipulating a Militant Group” report,

“On April 18th, Sergeant Detective Robert Lessard instructed his undercover agent to attend a joint general assembly of the CASA (Welcoming Committee of the Summit of the Americas) and CLAC (Convergence of Anti-Capitalist Struggles). (…) The list of targeted individuals of this surveillance operation was composed of three militants of the Québecois Emile-Henry group, three militants of the CLAC Montréal, one individual from the Boston anarchist group Barricada, and one individual from the US anarchist group Sabate (also from Boston).”

Still blissfully unaware as to just how much we were in the crosshairs of state surveillance and repression, we set out the next morning with joyful determination to participate in a second day of confrontation in the streets of Québec City.

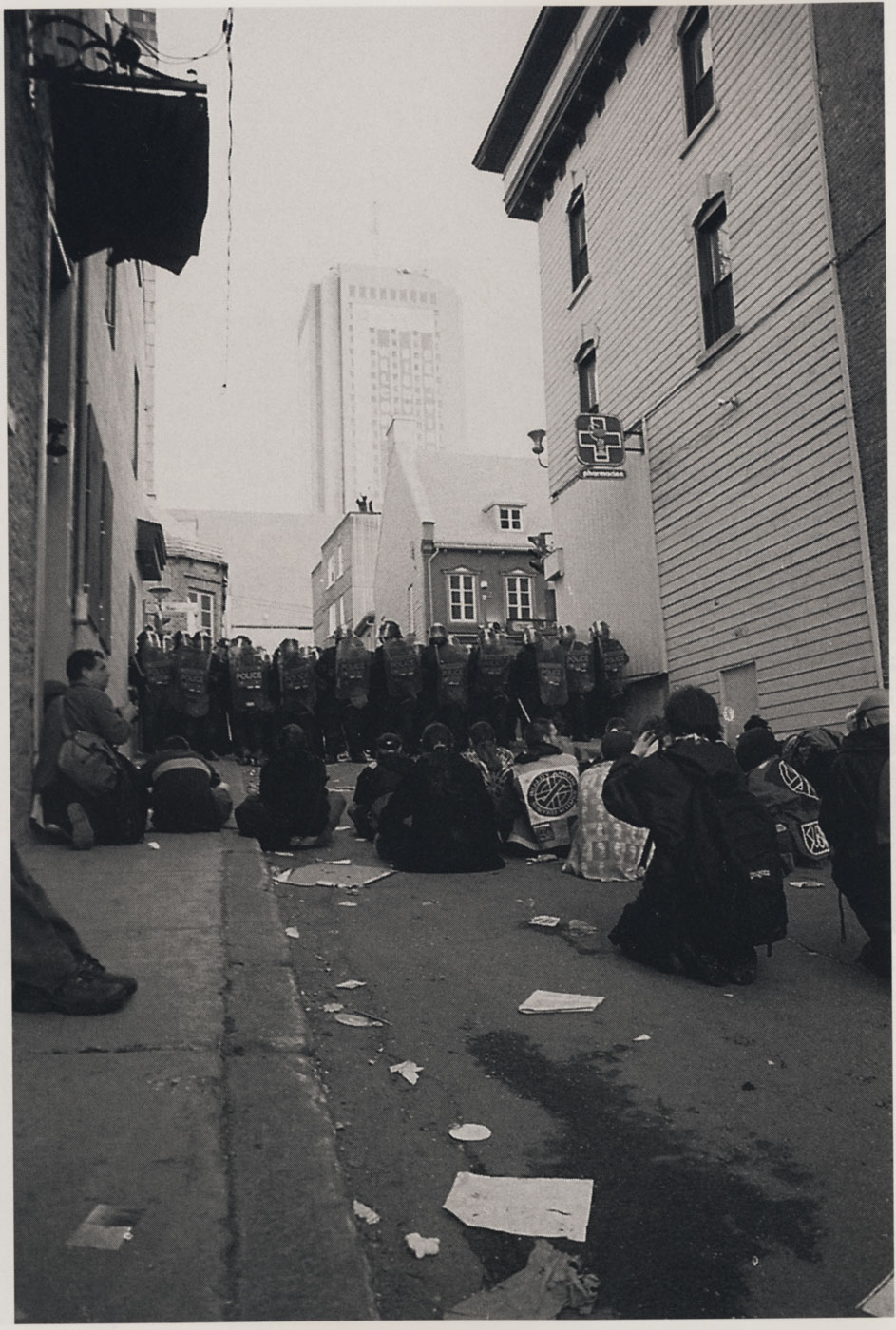

Saturday, April 21, Approximately 4 pm: Into St. Jean Baptiste

The day began with a permitted march composed primarily of “Canadian unions, progressive organizations, and assorted activists” which drew close to 40,000 people, making “its way through the lower part of the city, far away from the FTAA meetings and the security perimeter” where it “ended in an empty lot.” One member of the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) was clearly upset and could be heard asking “Why was the ‘legal protest’ conducted miles away from the security perimeter? Had I known I was marching towards a parking lot, I would have stayed home and done that at the fucking mall.”22

“Of course, not everyone followed the march to its final (non)destination. About halfway through the march, a de facto coalition of Wobblies, Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), Canadian Auto Workers (CAW), black bloc anarchists, and radical cheerleaders” broke off from the official protest march of the more mainstream organizations and headed towards the fence on Boulevard René-Lévesque. “Along the way, a couple of bank windows got smashed in, and at one point several anarchists ran down a side street and returned rolling a dumpster full of long wooden sticks and projectiles.”23

On the way towards the fence, the bloc entered the neighborhood of St. Jean-Baptiste for the first time that weekend (at least in an organized and collective fashion). The reception we received was incredibly moving. “In a scene reminiscent of troops going off to fight a popular war, battle-ready militants marched up the hill and through the St-Jean Baptiste neighborhood while hundreds of people lined the streets and hung out of windows to greet them with loud cheers of support.”24

“As one middle-aged mother observed while members of the Québec Black Bloc hugged each other before going off to battle the cops, ‘I always thought this was going to be sinister, but these are just brave kids.’”

“Blocs, Black and Otherwise,” CrimethInc., 2003

History was on our side in St. Jean Baptiste, in a more immediate sense than usual. The neighborhood we were entering was one of North America’s few remaining working-class areas in what are otherwise gentrified and corporate urban cores. It was adjacent to where the summit congress center was located, and a significant part of the security perimeter’s despised “wall of shame” ran through it. St. Jean-Baptiste also happened to be “a hotbed of radical activism,” in the words of Nicolas Phebus.25

But while the immediate history of the neighborhood made the terrain that much more fertile, and the actions and security strategies of the authorities had enabled anarchists to present a clear and simple alternative to locals, none of that would have been enough if not for the principled and committed day-to-day efforts of local anarchists.

“Some local anarchists and radicals have been active for a few years in the organization that is responsible for most of this local activism: the Comité Populaire Saint-Jean-Baptiste. The Comité Populaire is a 25-year-old community group that is part anti-poverty group, part citizens committee, and part popular education group. Although it is by no means ‘well funded,’ the organization still has a few valuable resources, including a widely read free quarterly newspaper, l’Infobourg, a weekly lecture program, l’Université Populaire, an office in the middle of the neighborhood with computers, fax, and telephone, and a little bit of money.”

-“Did We ‘Radicalize This’? An Insider’s Look At The Québec Protests,” The Northeastern Anarchist #2

Today, Phebus remains unequivocal about his opinion, shared by many local class struggle anarchists and Comité Populaire members, that “most of the anti-globalization activists, and most anarchists for that matter, were middle class and bourgeois and didn’t give a fuck about working-class people and lumpen people,” while the Comité Populaire was precisely a community organization of poor and working-class people, whose task it was to defend their material and class interests.26 “We were interested in fighting the local effects of neoliberalism. We were into fighting for tuition freezes at the university, for social housing, against welfare reform, against unemployment insurance reform, and so forth. We were basically fighting against the concrete application of neoliberal policies in the national social system. Of course, we know that there is a link between globalization treaties and those policies. But we felt that the real issue was poor people’s conditions, not how the market operates. In our view, activists were more interested in the conditions of the indigenous in Chiapas than of their neighbors in the inner city.”

Phebus recounts that, despite this, the Comité Populaire stopped seeing the impending summit as a distraction when “it began to clash with the daily lives of the people in Québec City. When it became obvious that it would impact everyone in the city for months. That it would make life miserable for everyone downtown.” This became abundantly clear when police announced their plans to erect the security perimeter a full month ahead of the beginning of the summit—and to allow only those with “resident cards” into the security zone. From this point forward, the Comité Populaire took the lead in an impressive community outreach campaign. Organizing autonomously outside of any broader coalitions, the Comité Populaire refused to participate in debates about “violence” versus “non-violence.” And while “everyone was talking about the FTAA,” the Comité Populaire “decided to talk about the summit, the cops, and the fence.”

“We felt that globalization was way beyond anyone’s interests. That the way to reach people was to discuss the security measures and organize against the fence. So in addition to the general agitation against the FTAA and anti-capitalism, we developed a campaign around the security measures. We formed a group in the neighborhood with the Comité Populaire, an unemployed workers union, CASA, and one other community group. We held a general assembly open to anybody, drew up a leaflet, and decided on a plan of action. Instead of having a flurry of little actions, we decided to focus on two main things—a demonstration and a public assembly in the neighborhood about the fence. (…) We drew up a leaflet and printed about 4500 copies, which is a little bit more than the number of doors in the neighborhood. We distributed them to everyone, and the cops made a terrible mistake. They arrested one of our crew who was distributing flyers, simply for refusing to identify themselves, which made national news and the front page of local dailies.