Zine :

Lien original : Ill Will, par Jarrod Shanahan

En français :

In an essay published early in the George Floyd Rebellion, Martin Schoots-McAlpine discusses the nascent counter-insurgency carried out by “various police forces, the capitalist media, the American military, NGOs, the Democrats, both state and federal governments, and other liberal establishment figures” [1]. Drawing on the work of Kristian Williams, he argues that police violence is only one side of counterinsurgency. The other side, soft counterinsurgency, works through institutions commonly considered “progressive,” like local non-profit organizations and progressive political machines, which worked to discipline and defang rebellion of its militant character and render it yet another performative and ultimately fruitless exercise in speaking truth to power [2].

This strategy is nothing new. Civilian leadership in cities across the U.S. emerged from the urban rebellions of the 1960s with a new approach to managing social order, based on incorporating community organizations within city governance. State power, and hence police power, could therefore be grounded in the consent of a critical mass of local notables, typically from the petty bourgeoisie, who would be willing to defend the cops, politicians, and capital, against radical challenges to the social order [3]. The role of the cops in this strategy is the business of grooming informants, building trust through daily interactions, and cultivating cooperative relationships with local non-profit organizations, schools, political machines, and churches, in an effort to make these institutions and actors adjunct on demand to police work. Hollywood, and even Madison Avenue, have also been at the service of beleaguered police departments since the 1960s, creating an impressive ideological machine that produces proletarian support for the cops [4].

The daily practice of counter-insurgency by police has come to be called “community policing.” Community policing aims to isolate and marginalize the rowdiest and most radical elements of working-class communities. Its intent is to cultivate police legitimacy in the eyes of a critical mass of the “good” citizens, as a base of support for selective police violence against the “bad” ones. “Community policing is not about making police friendlier,” write David Correia and Tyler Wall, “but rather about making police violence more acceptable” [5]. When applied to struggles like the George Floyd Rebellion, this strategy calls for splitting off “good protesters,” who are deemed non-threatening and co-optable by the state, from “bad protesters,” who pose threats to private property and social order, such as looters, arsonists, and those who refuse to passively receive police violence [6]. If the police are successful, the good protesters can become the cops’ best asset in crushing the bad ones.

The business of counterinsurgency is, however, far from one big happy family. With exceptions that prove the rule, U.S. police are hardly enthusiastic partners in community policing or other soft counter-insurgency schemes. One of the main reasons is simply that they don’t have to be. As police increasingly assumed the role of managing social order amid the social turmoil of urban rebellion, deindustrialization, austerity, and in particular, state disinvestment from working-class communities of color, they have demanded and received increased social power and the freedom from civilian scrutiny over how they do this job. Politically untouchable and immersed in a macho culture of honor that brooks no affront to one’s toughness and dominance, U.S. cops are unwilling to tolerate even the most symbolic checks on their almost boundless authority. These include civilian review boards with no real authority, performative consultation with “community leaders,” and often, it seems, simply being told to be nice [7]. The way that cops and their unions consistently reject oversight and close ranks around colleagues, no matter what they’ve done, indicates that the U.S. police view their ability to mete out violence indiscriminately as a barometer of their political power, and understand any checks on their behavior, no matter how symbolic, to be an existential threat [8].

In short, while the liberal regimes of major U.S. cities emerged from the 1960s with a sophisticated strategy for managing social order through cooptation and consent, an organized critical mass of cops believe that fear, backed by violence, is the basis of their legitimacy. This tension accounts for the often perplexing conflict surrounding technocrats like New York’s mayor Bill de Blasio and Chicago’s Lori Lightfoot, who are bitterly detested by local police and their right-wing allies, despite being milquetoast at best in actually opposing much of anything the cops do. However, while it is common in leftist discourses to accuse these and other mayors of leading their police departments like generals in the battlefield, the relationship between civilian authorities and the cops is at best an uneasy peace. In times of crisis like the George Floyd Rebellion, it often becomes clear that they are operating with different approaches to maintaining social order, which should be of interest to anyone seeking to take direct action on this overdetermined political terrain [9].

This conflict between rival counterinsurgent strategies can be studied in detail in the pages of the New York City Department of Investigation’s (DOI) December 2020 report Investigation into NYPD Response to Floyd Protests [10]. The DOI represents a legalistic, technocratic approach to City governance, akin to the pioneers of the city’s soft-counterinsurgency strategy, and the architects of community policing. Accordingly, they are not happy with how the NYPD responded to the George Floyd Rebellion.

DOI puts the problem, as they see it, quite succinctly: “Public trust and legitimacy are essential for the police to perform their vital work and honor their duty to serve and protect the public” (p. 1). Invoking an explicit social contract narrative, DOI argues that police powers are granted by public consent, in exchange for the cops undertaking the dangerous business of maintaining social order. The cops are thereby duty-bound to serve their function without prejudice, purge bad actors from their ranks, and make their actions transparent and accountable to the public. This contract, DOI argues, is the source of their legitimacy (p. 1). In protest situations, DOI even suggests that cops enter an explicit verbal contract with protesters, informing them “the police will facilitate free expression as long as they are peaceful and law-abiding” — thus effecting a cleavage between the good and bad protesters, earning legitimacy in the eyes of the former, and gaining their consent to crush the latter (p. 41).

Conversely, DOI argues, “[r]esearch suggests that police action that is perceived as overly aggressive against protesters can increase the risk of confrontation, as moderate participants become more likely to shift their sympathy toward more radical participants who may be inclined toward police-directed violence” (p. 33). Not only, then, does police violence undercut their legitimacy in the long run, but it also acts as an accelerant in moments of social conflict, radicalizing moderates who would otherwise be potential allies of the cops. In responding to the rebellion, DOI finds that instead, NYPD consistently deployed a “disorder control” methodology, aimed at quickly restoring order through indiscriminate arrests and the wholesale deployment of violent tactics like clubbing, kettling, pepper spraying, and sometimes punching and kicking protesters, with no regard for the First Amendment, the political sensitivity of the protests, or differences between the protesters. DOI notes how NYPD consistently “failed to discriminate between lawful, peaceful protesters and unlawful actors,” meaning that treated the good and bad protesters with equal severity, which sometimes extended to street medics, legal observers, and the press (pp. 3-4, 41-44). By refusing to distinguish between good and bad protesters, DOI argues, and relying heavily on its Strategic Response Group (SRG) unit, designed and trained to quell riots and respond to acts of terrorism, NYPD significantly escalated the rebellion (pp. 34-36).

DOI is particularly concerned about the NYPD refusing to give special consideration to the rebellion’s basis, police violence, which made protests even more likely to be escalated by police violence (pp. 35, 40). This is of course wishful thinking on DOI’s part, as the chatter on the rank-and-file cops’ unofficial forum Thee Rant, the words of both cop union representatives and NYPD brass, and the behavior of countless rank-and-file cops in the street all indicate that cops were profoundly aware of the nature of the rebellion and considered it an enemy to be cowed into submission, conquered not by consent but by brute force [11].

In either case, DOI cites best practices in counterinsurgency that consider protesters in terms of their place in a hierarchy of “laddered groups”:

(i) the general public who care about the issue but are rare or occasional participants in protest activity; (ii) organized traditional issue groups with members who are experienced protesters; (iii) radical or fringe groups who eschew coordination with authority and may affirmatively advocate violence or property destruction; and (iv) non-ideological opportunists (e.g. looters) (pp. 37-28)

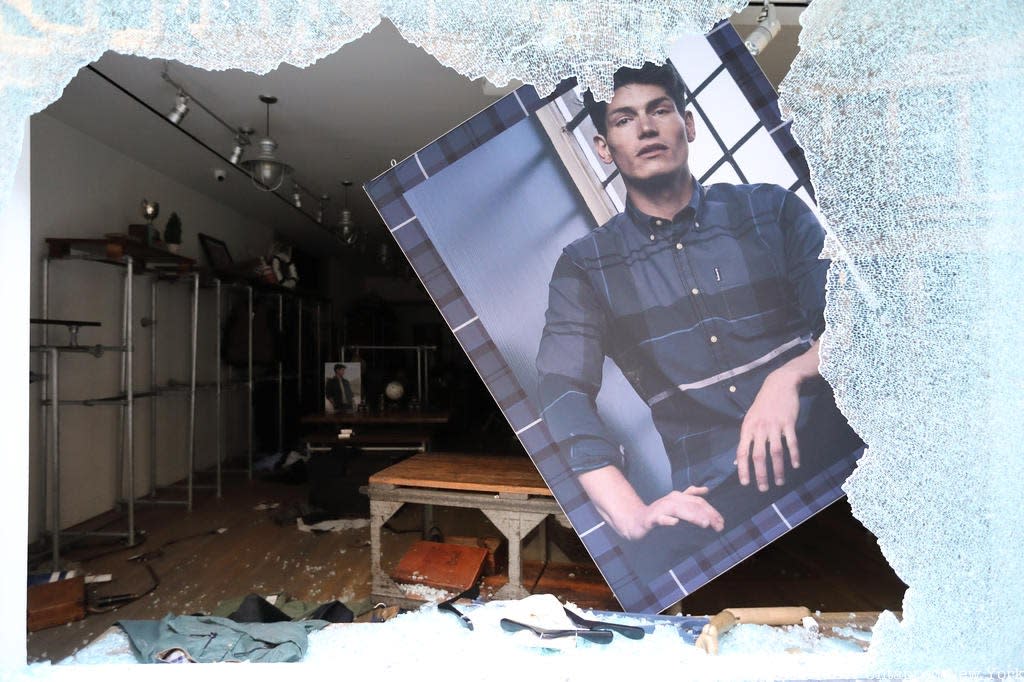

If they wish to follow best practices, DOI argues, NYPD should seek to make common cause with the first two groups, shoring up legitimacy through cooptation, as a precursor to smashing the latter half with whatever force is necessary. Similarly, Mayor de Blasio’s executive order declaring an emergency curfew specified that curfew enforcement was not meant to curtail the good side of the rebellion, but was instead responding to actions “subsequently escalated, by some persons, to include actions of assault, vandalism, property damage, and/or looting” [12]. DOI is similarly invested in foregrounding the peaceful aspects of the rebellion and casting it as a largely innocuous exercise in the First Amendment, marred by “individuals seemingly unaffiliated with the protests [who] used the opportunity to engage in looting” (pp. 7, 34). This of course makes the spurious assumption that looting is not a form of political dissent, deftly deconstructed by Vicky Osterweil in In Defense of Looting, but more importantly, cuts to their imperative to separate out the bad protesters from the good [13].

Most tellingly, DOI finds that NYPD made virtually no use of Community Affairs, its explicit “community policing” arm, often deployed to protests as a means of de-escalation. DOI writes that “Community Affairs officers at protests aim to maintain peace, engage with organizations about plans for protest activities, and promote positive communication between the police and protesters… by walking the crowd, speaking with participants, and then relaying relevant information to the Operations Division.” In short, they solicit (and receive) cooperation from protesters. Community Affairs also gathers “intelligence” on how police can best manage the disorder of protests, and builds partnerships with “local clergy, elected officials, and other community groups.” The cops can then deputize as de facto police agents, using them to gather intelligence, mediate “disputes or conflicts,” and most importantly, help erect a firewall between the good protesters and the bad protesters, with the former effectively jettisoned to the police, against the latter (pp. 63-64).

In short, Community Affairs represents a sophisticated community policing vehicle already existent within NYPD, which the department made practically no effort to mobilize throughout the rebellion. While DOI takes issue with the exclusion of Community Affairs cops from NYPD’s protest plans, this evinced NYPD’s broader lack of interest in a soft-counter insurgency strategy of any kind, and its reliance instead on SRG and a strategy of hard counter-insurgency. DOI found this also defined the department’s media strategy, which emphasized the illegality and violence of the rebellion, making no overtures to its good protesters or their numerous sympathizers in the public. Additionally, they found the NYPD was more interested in using intelligence to justify cracking down wholesale, rather than using it for the soft counter-insurgent purposes of separating out the good from the bad protesters (pp. 37-39).

In response to what it considers the systematic failure of the NYPD to effectively respond to the George Floyd Rebellion, DOI has made a number of reform recommendations, chief among them the need to adopt community policing methodology for large-scale protests, build ties with “community organizations and issue-advocacy groups,” improve its public relations strategy to offer more conciliatory messaging in times of crisis, and to modernize and streamline the unwieldy network of police oversight boards that currently exist (pp. 68-71). In place of pacification by brute force, DOI suggests NYPD adopt a “facilitation mindset,” which enables cops “to actively facilitate peaceful and lawful protest even while taking enforcement actions against people engaged in violence or property destruction” (pp. 37-38). Page after page, they implore the NYPD to recognize the distinction between good and bad protesters, in order to rout out the latter with the cooperation of the former.

In fairness, NYPD’s approach perhaps cannot be attributed to pure belligerence. DOI emphasizes NYPD’s own admission of being caught off guard by the size, scope, and ferocity of the protest, and the department’s flailing to keep up with such a massive event in its early days (p. 3). This is largely thanks to decisions made by the rebels themselves. Cops complained to DOI that “while groups and organizers familiar to NYPD organized some of the demonstrations during the Floyd protests, relatively new leaders and groups, or leaderless protests, were common and were coordinated, if at all, largely by communication on social media shortly before or during the protests themselves.” Moreover, NYPD complained of “ideological opposition among some of these new leaders and organizations to coordinating with police regarding the plans for their protests,” which they contrast with much of the established protest leadership (p. 53). NYPD also noted the difficulty of policing “laddered” crowds, or crowds that presented a heterodoxy of militants, looters, and more traditional protesters (pp. 37-38). It seems the refusal of rebels to self-segregate in terms of ideology or tactics, and a baseline tolerance of a diversity of tactics among the more politically moderate participants, made the work of the cops more difficult. Finally, cops claimed that widespread use of the “de-arrest” tactic escalated street confrontations and contributed “partly by design… to a sense of chaos and mayhem,” which thereby led to increased violence and more arrests (p. 53). This of course must be taken with a grain of salt, as the cops were all too happy to crack down indiscriminately without any provocation.

So what does this all mean for the people out in the streets? On the most basic level, any substantive conflict within the ruling class should be of keen interest to those seeking to push beyond the bounds of legality. It was an interesting feature of the rebellion that while the far-right, including President Trump and police unions across the country, consistently pointed to the movement’s violence and property destruction, liberal institutions downplayed the rebellion’s insurgent quality and underscored its peaceable, almost patriotic nature [14]. Liberal politicians were forced into the uncomfortable position of having to either support or reject the movement wholesale, as both the rebels and the cops/right wing bucked the distinction, insisting instead that one either be for or against the rebellion as a whole. This created tactical openings where rebels could push the envelope, knowing that their enemy was distracted and divided.

More broadly, the report attests to how difficult the business of counterinsurgency can be when there is no buy-in from the activist left. NYPD was thrown off guard by the breaking of the ordinary protest script, by a refusal of protesters to buy into the good/bad dichotomy, and by a degree of militancy and courage not seen on the New York’s streets in such numbers in a long time, if ever. The downside, of course, is NYPD doesn’t just pack up and go home when they can’t parcel out the good protesters from the bad. Instead, they just smash everyone, and which is what many of them wanted to do in the first place. But DOI is rightfully wary of this method of maintaining order, for the simple reason that it is ineffective when compared with soft counter-insurgency. In the short term, indiscriminate police violence can escalate rebellions and radicalize moderate participants, leading to an influx of rebels, more militant tactics, and a general state of decreased governability. On a long enough timeline, indiscriminate police violence leads to the widespread delegitimization of the police in the eyes not just of the left-wing protesters who distrust or hate them already, but the broader swaths of the social fabric whose participation in a rebellion could turn it into an outright revolution.

It however is worth remembering that absent substantive soft-counterinsurgency by NYPD, the rebellion nonetheless hit its limits [15]. The reasons are beyond the scope of the present discussion, but it must be stated clearly that the NYPD’s escalation through violence did not suffice in itself to propel the rebellion indefinitely. Additionally, while the rebellion in NYC was escalated significantly by rebels’ widespread rejection of the good/bad dichotomy and the courageous adoption of militant tactics, this came at a high cost, including untold injuries, and thousands of arrests ranging from bullshit charges meant to clear the streets to serious felonies [pp. 23-29].

While the DOI states time and again that indiscriminate violence and arrests can have an accelerating effect on rebellion, it must also be remembered that brute repression is not completely ineffective. It takes an undeniable toll on movements by traumatizing, demoralizing, and downright scaring people away or sidelining them with court cases. Thus, while the refusal of a critical mass of NYC rebels to play by the ordinary protest rules surely enabled the rebellion to go further than it would have otherwise, the cost of this victory must not be ignored. Ultimately, it’s worth keeping in mind that an all-out meeting of violence against violence is exactly what many cops want in the first place, and given the present balance of forces, it would almost certainly be decided in their favor. What precisely this means for strategy moving forward must be debated and decided among those with skin in the game.

January, 2021

Notes

1. Martin Schoots-McAlpine, “Anatomy of a Counter-Insurgency: Efforts to Undermine the George Floyd Uprising,” MR Online, May 25, 2020.↰

2. Kristian Williams, “The Other Side of the COIN: Counterinsurgency and Community Policing,” Interface: A Journal for and about Social Movements. May, 2011. ↰

3. Robert Allen, Black Awakening in Capitalist America, excerpted in INCITE!, The Revolution Will Not Be Funded, Boston: South End Press, 2009; Karen Ferguson Top Down: The Ford Foundation, Black Power and the Reinvention of Racial Liberalism, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013; Jarrod Shanahan and Zhandarka Kurti, “Managing Urban Disorder in the 1960s: The New York City Model,” The Gotham Center for New York City History, January 7, 2020.↰

4. For an early account of LAPD’s pioneering experiments in public relations, see: Linda McVeigh Matthews, “Chief Reddin: New Style at the Top,” Atlantic, March 1969, 84-93. ↰

5. David Correia and Tyler Wall, Police: A Field Guide, New York: Verso, 2018, 130.↰

6. Jarrod Shanahan and Zhandarka Kurti, “The Shifting Ground: A Discussion of the George Floyd Rebellion,” Ill Will, September 10, 2020.↰

7. Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis and Opposition in Globalizing California, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007; Rebecca Hill, “‘The Common Enemy Is the Boss and the Inmate’: Police and Prison Guard Unions in New York in the 1970s–1980s,” Labor: Studies in Working Class History of the Americas 8, no. 3 (2011): 65–96; John Garvey and Jarrod Shanahan, “Police Rebellion, Then and Now,” Hard Crackers: Chronicles of Everyday Life, June 23, 2020.↰

8. Natasha Lennard, “Police Unions’ Opposition to Prison Reform Is About More Than Jobs — It’s About Racism,” The Intercept, August 14, 2018.↰

9. I have elected to flatten what is at least two distinct dynamics – rank-and-file NYPD cops and their commanders – into the singular figure of the NYPD. While there is no shortage of tension and antagonism between these forces (and a number of gradients within each category), the report this article discusses evinces a remarkable consistency between the attitudes of commanders and the actions of their rank-and-file. This is a testament at once to the famous insularity of police culture, but also the political power of rank-and-file cops to demand the loyalty of their superiors.↰

10. New York City Department of Investigation (DOI), Investigation into NYPD Response to Floyd Protests, December 20202. Subsequent citations are in-text. This report came amid a similar investigation and subsequent lawsuit by State Attorney General Leticia James. See: Shayna Jacobs, “New York Attorney General Sues NYPD over Handling of George Floyd Protests,” Washington Post, January 14, 2021.↰

11. “Thee Rant”; Sidney Pereira, “‘The Streets Were Out Of Control’: NYPD Chief Defends Violent Police Tactics During George Floyd Protests,” Gothamist, June 11, 2020; William Finnegan, “How Police Unions Fight Reform,” The New Yorker, July 27, 2020.↰

12. Mayor Bill de Blasio, “Emergency Executive Order No. 117, Declaration of a State of Emergency,” June 1, 2020, my italics. ↰

13. Vicky Osterweil, In Defense of Looting, New York: Bold Type Books, 2020.↰

14. Idris Robinson, “How it Might Should be Done,” Ill Will, July 20, 2020.↰

15. Shemon and Arturo, “Theses on the George Floyd Rebellion,” Ill Will, June 24, 2020; New York Post-Left, “Welcome to the Party: The George Floyd Uprising in NYC,” It’s Going Down, June 24, 2020.↰