Zine :

Lien original : via CrimethInc

As students prepare to return to an increasingly dystopian learning environment, it’s a good time to revisit our assumptions about education itself. What is the purpose of our educational institutions? How deeply do the premises of those institutions shape the ways that we approach learning, even in our “free time”? How else might we go about developing and exploring our capacities?

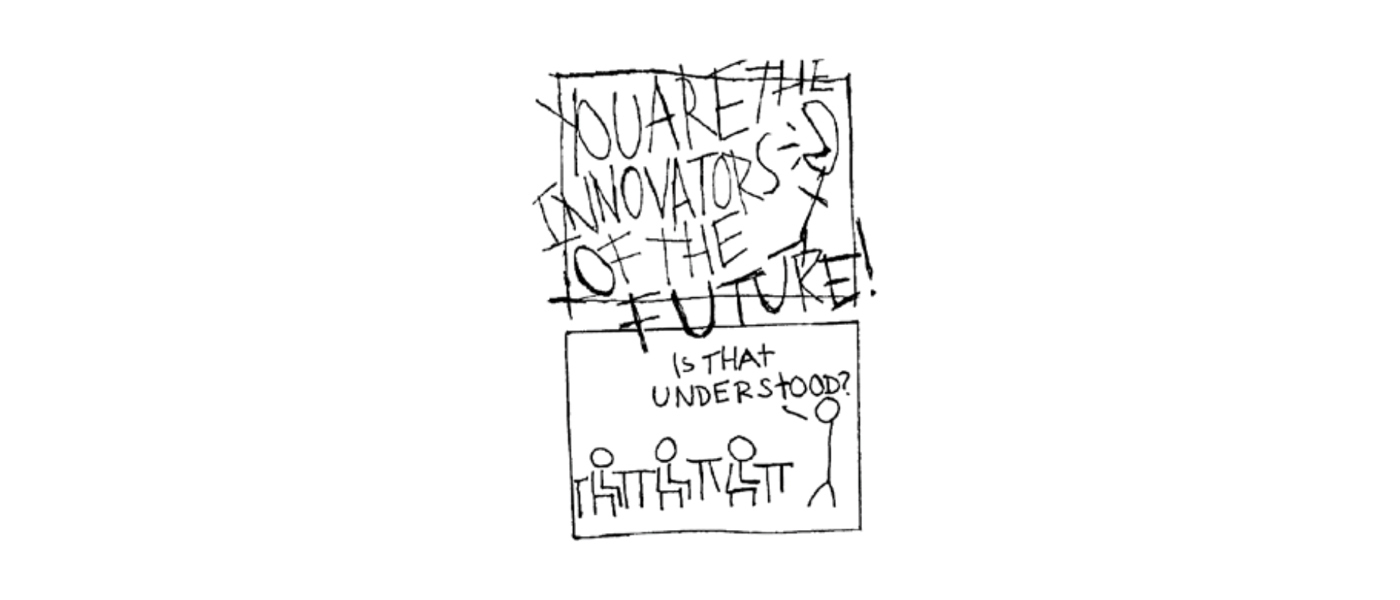

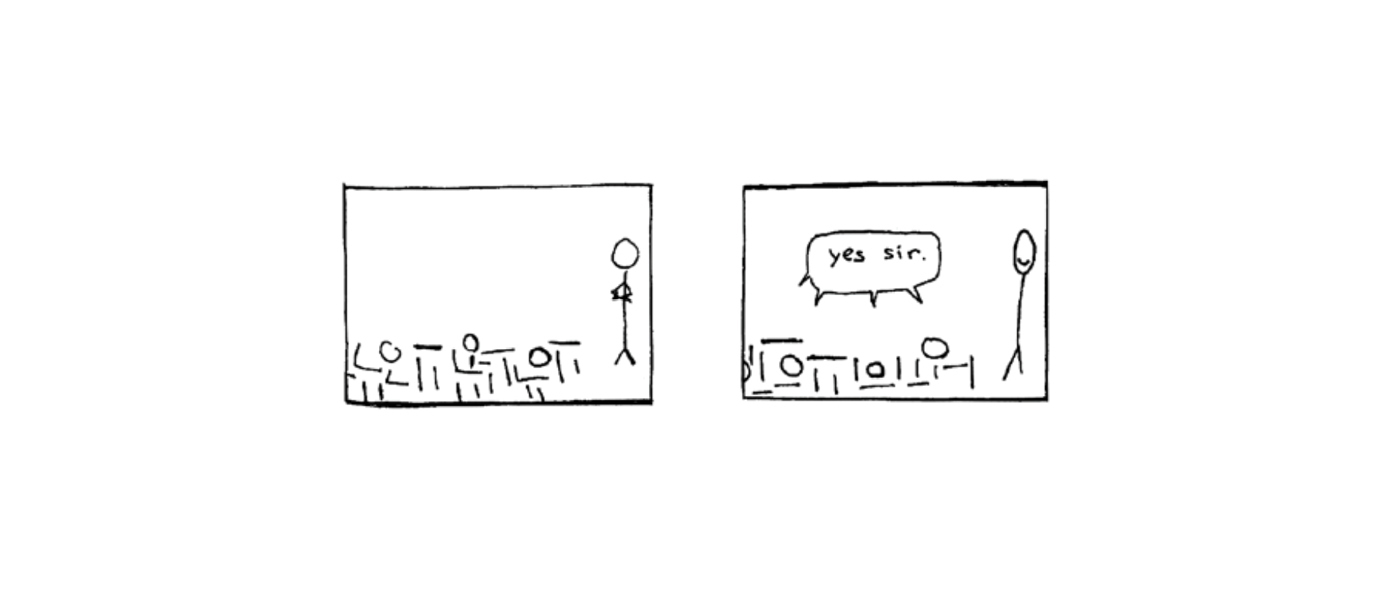

“Education is what survives when what has been learned has been forgotten,” B. F. Skinner put it. In other words, the function of education is not to enable the learner to acquire specific skills or knowledge so much as to inculcate certain habits and ways of thinking. In a hyper-capitalist society, in which educational institutions chiefly serve to rank and categorize job applicants, the role of schools is not just to prepare us for the working world, but to resign us to it, reducing our ability to imagine any other form of learning.

The following text originally appeared in 2005 in the first issue of Rolling Thunder, our Anarchist Journal of Dangerous Living. In the years since, between declining employment prospects and “remote learning,” the horizon students face has only become bleaker. Today, as an alternative to formal commodified schooling, the internet offers a space in which self-directed learners can acquire information, albeit in an abstract and alienated form. But if we really want to depart from the model represented by authoritarian educational institutions, we have to rethink learning from the ground up.

Deschooling: Unlearning to Learn

To speak of deschooling is to speak in favor of doing—engaging in self-directed, purposeful, meaningful activity—and against education—in the sense of learning directed from above, cut off from every other sphere of life and carried on under pressure of bribe and threat, greed and fear. It is to speak about people doing things, and doing them better, and the conditions under which this can be possible; about some of the ways in which, given those conditions, other people may be able to help us to do things better, and vice versa; and about the reasons why these conditions do not exist within compulsory, coercive, competitive schools or even so-called alternative learning institutions.

Performer and Performance

Your average music student thinks of music as a thing to learn, not a thing to do. Yet despite academies and conservatories, methodologies and method books, pedagogies and pedagogues and millions of rapped knuckles, the proper active verb in relation to the word music is still “to play.” You play music. You can also make music. Playing and making are the essential elements of being a musician. Yet instead of playing and making, the student practices compositions or works on assignments. If you practice, the implication is that you aren’t really doing it. You are always in preparation for when you’re really going to do it. Well, when are you really going to do it? At a lesson for your teacher? For an adjudicator in an exam or a judge in a competition? For parents or friends? Once you’ve really done it and your parent, teacher, or judge lets you know whether you’ve succeeded in making music or not, will you ever want to do it again?

In a product-oriented society, performance (recording) and performer (persona) become the most important features of music, crucial because they are eminently marketable. The only real music is the stuff that passes the ultimate test of commodification. When you “perform” at a lesson or on request for relations, and you haven’t been practicing and doing the work you know you should have been doing and you fail to perform up to everyone’s expectations—real or imagined, including your own—you feel bad. You do not feel like a musician. You may feel like lying. You may dislike yourself and feel guilty. You may resent your teacher and parents for putting you through all of it. You may feel all these things even more intensely if you were the one who wanted the lessons in the first place! Whatever you feel, you certainly won’t feel musical.

Enforced regimens cannot protect young people from the many failures and tragedies adults have lived through. Music can only be enjoyed on its own terms. The focus on performance initiates a complex of feelings: frustration at doing poorly, resentment that it takes so much work to be “good,” confusion about music not being any fun at all. Ultimately, the student may resist practicing altogether. All this runs counter to the other purposes of playing music: to be “a more well-rounded person,” to acquire another form of expression, to have fun. Outside pressure of this sort is antithetical to learning and living.

What most people call “education” entails the assumption that learning is an activity separate from the rest of life, that is done better when one is not doing anything else and best of all where nothing else is done— in learning places especially constructed for learning alone. Most use the term “education” as if it referred to some kind of treatment. Even “self-education” can reflect this: it can be seen as a self-administered treatment. But it is utter nonsense to say that people need to be taught how to learn or how to think. We are born knowing how to do so. We are born with the inclination to play, and in doing so, we do not live a single moment without learning.

The Origins of Compulsory Schooling

The structure of 20th century schooling in the United States dates back to 1806, when Napoleon’s amateur soldiers beat the professional soldiers of Prussia at the battle of Jena. When your business is selling soldiers, losing a battle like that is serious. Almost immediately afterwards, a German philosopher named Johann Gottlieb Fichte delivered his famous “Address to the German Nation,” which became one of the most influential documents in modern history. In effect, he told the Prussian people that the party was over, that the nation would have to shape up through a new utopian institution of forced schooling in which everyone would learn to take orders.

Thus compulsory schooling arrived in the world—at the end of a state bayonet. Modern forced schooling started in Prussia in 1819, with a clear vision of what centralized schools could deliver: obedient soldiers to the army, obedient workers to the mines, well-subordinated civil servants to the government, well-subordinated clerks to industry, and citizens who thought alike about major issues. Thirty-three years after the fateful invention of the centralized learning institution, the US adopted the Prussian style of schooling as its own.

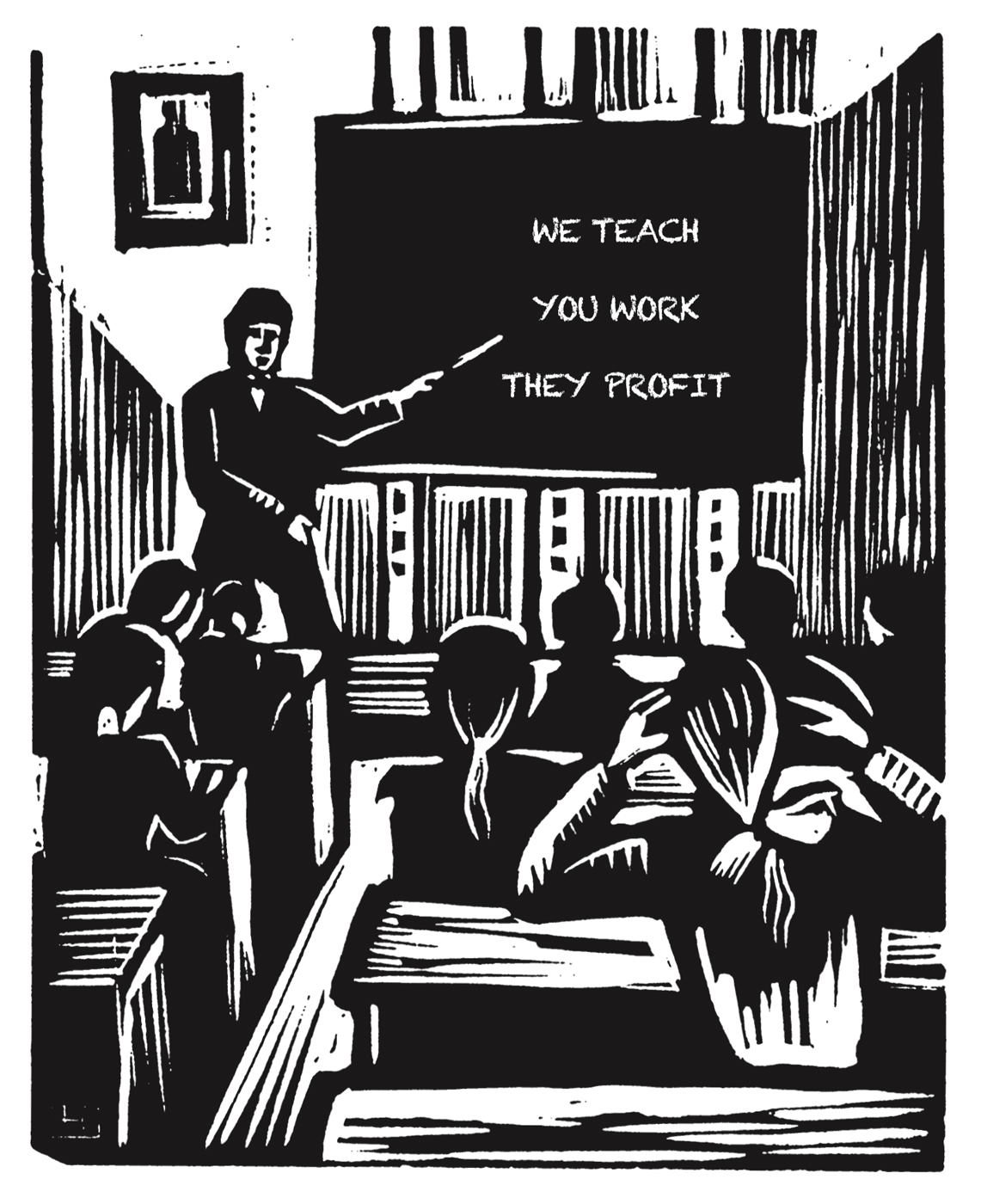

Education as Industry

Compulsory education is still meeting our superpower society’s need to train citizens for subservience. In addition, education now prepares people for careers in various industries that Fichte couldn’t have imagined in his time. The biggest surprise of all is that education has itself become an industry. In a progressively mechanized world, in which self-checkout at the grocery store and e-ticket computer check-in at the airport are replacing the jobs that once kept citizens busily integrated into society, what can be done with all the surplus workers except to postpone endlessly their entry into the workforce?

It is said that today’s high school graduates can be sure that, if they are to have jobs at all, they will perform tasks we cannot even imagine yet. In the limbo between the known and the unknown, there is education. Teachers and administrators can always be employed when other jobs are scarce, and those taught to believe they won’t be ready to live life until they’ve been properly prepared form a ready mass of consumers. Would-be employees spend progressively more and more time competing with one another for an upper hand, an extra point, a longer list of credentials. This is an effective way to divert attention from the impending doom of unemployment and a ready explanation for why people some never get the dream jobs they thought awaited them—they just didn’t study enough.

Once upon a time, only the rich and powerful sent their children to school. In today’s credit-based economy, in which everyone is expected to be middle class and most must live beyond their means to maintain this illusion, the education industry has made a killing with a new form of protection racket. In order to be equipped for employment of all but the worst kinds, people must pay thousands or tens of thousands or even more to go to schools that teach few of the skills the job market actually requires. This traps them in debt for decades, forcing them to go on to sell themselves wherever the economy will have them. It’s a highly sophisticated form of indentured servitude. Is there really no more “educational”—let alone worthwhile—way to spend that much money? And would so many students, fresh out of college and desperate to live freely for once, immediately seek employment if they didn’t have such crippling debts to pay off?

Dropouts and Deschoolers

Most people born with a parent or two find themselves in the smallest and most immediate socializing institution—a family. From the perspective of the government, this old-fashioned institution is unreliable and unsurveillable. Schools and daycare systems, in complementary compulsory and voluntary models, ensure that children absorb certain values. Accordingly, a wide variety of families, interested in self-governance for any number of reasons, plan ahead to deschool.

In pop culture, these homeschooling and non-schooling families are represented as hippies, religious fundamentalists, or extremist freaks. We are told that many of them are rich and white. We rarely see information about homeschooling families from targeted or marginalized demographics. Many of these families prefer to remain anonymous: many Black parents fear that if school authorities discover how readily they’ll remove their children from school, lawmakers will design laws to force them to bring their kids back. Black homeschoolers have cause to fear the government will enact truancy laws, like the fugitive slave laws, that will have a more serious impact on their families than on more privileged ones. It is also likely that, because of greater access to resources, tools, time, and a feeling of being entitled to bend the rules, wealthier and whiter families are more prevalent in the formal homeschooling world.

Of course, many of the unschoolers out there are isolated in their principles—not only from the system they refuse, but also from their parents. For the sake of deschooling, we should work to rid our minds of the prejudices that would have us view those who drop out of educational treatment as “failures” or “delinquents,” strays who must be caught and brought back into the fold. When we hear these things about school dropouts, we hear them from the point of view of the dogcatchers. Instead, we could view dropouts as refuseniks, conscientious objectors to a stifling and dehumanizing process. Many students whose caretakers defined them as dropouts have since redefined themselves as successful escapees from a useless educational career.

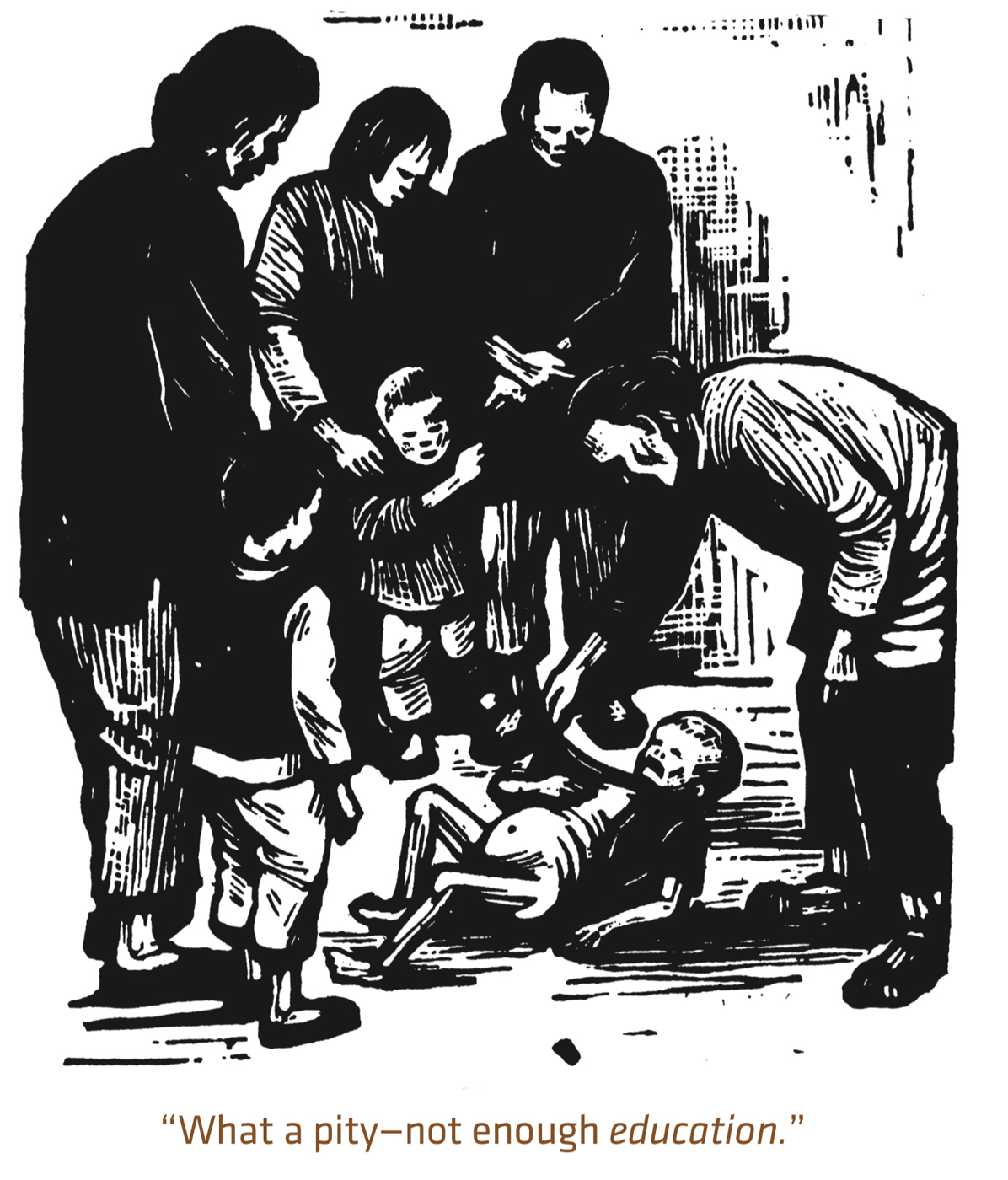

In the USA, the vast majority of young people who drop out before graduation are Latino and Black. By the time they leave school, they have been attacked in both soul and body. Understandably, many refuse further “care” after suffering through intensive remedial programs that imply that they are unable to succeed within the system or to make it into society at large by any route approved of by their teachers. In schools that teach them nothing about themselves, they have been forced to learn to fake everything. Many have come to see school as a worldwide soul-shredder that junks the majority and hardens an elite to govern the others.

This is the self-consciousness of the truant to which we all may aspire. Let us remove the stigma currently attached to educational underconsumers.

The Misadventures of Teachers in the Temple of Doom

Most teachers are generous, intelligent, creative people. Some are very talented or knowledgeable in their fields and would be great mentors or friends outside the constraints of school. Many have given up chances to make lots of money because they believe in teaching even though it pays poorly. Especially if they are men, they sometimes endure years of being hassled by their families—“why don’t you find a real career?” Many teachers are terrific people. But the role they are forced to play in school keeps them from behaving as real people in their interactions with certain other real people, that is to say, students. Their talent and energy is drained by the task of constantly telling people what to do. As instructors, these good people scrape their sides against concrete barriers as they take the bureaucratic twists and turns any school requires them to. This is the nature of the fundamental restraints of institutional schooling.

When you have a knowledgeable, funny, or wise teacher, listening to that person weave stories and lectures can be delightful—assuming, that is, that she is “allowed” by the administration to be herself and say what she truly knows and thinks. Unfortunately, this is seldom the case, since most education officials have to worry about offending any of the parents who might not re-elect them, and therefore strive to keep their teachers as mute, mediocre, and middle-of-the-road as possible. Nearly all those employed in a school live in fear of their superiors, because their superiors live in fear of their voting constituency. Democracy! Therefore, all the interesting ideas get censored down to the very lowest common denominator. The teacher can’t say, “Wait a minute, what’s fueling this so-called war on drugs?” because Johnny’s father, outraged, might call the principal to protest that “a teacher, of all people!” is encouraging drug use. Johnny’s father may in fact have serious doubts of his own about the war on drugs, but he isn’t likely to accuse the administration of brainwashing, either, lest others brand him an unfit parent—and a big ship like the Educational Curriculum isn’t easy to bring around.

Some of the brightest and most radically inclined people you could ever meet become teachers or professors, trying to get their footing in this bureaucratic mud to take a stance. School is one of the few socially ascribed places for “free thinkers” to do their thing. Now that the soil has been poisoned and cemented over and almost all human beings randomly deposited into vehicles, offices, prisons, and hotels, to speak of friendship, god and godlessness, or joint suffering is to be an academic dreamer.

What would happen if, instead of becoming academics who train other would-be academics, we thoughtful folks sought out our peers and sought to engage in mutual influence in more immediate and intentional ways? While opposing all pleas for new forms of institutionalized relations, we can dream of niches, free spaces, and squatted social centers—of tents and plazas and perhaps even occupied schools in which people can gather in groups according to who wishes to take on a project or explore a specific thought together. We can seek to create spaces in which we meet on the basis of a common desire for self-governance, renouncing all integration into any system.

Rethinking Discipline, Safety, Certification, Public Spaces, Child Labor, and Thinking Itself

Let us rethink discipline. One of the worst things about the arbitrary form of authority we see in the classroom is the way it makes us lose our trust in the possibility of learning from people who know what they’re doing and could share their wisdom with us. When they make you obey a cruel and unreasonable teacher, they can curtail your desire to learn from a kind and reasonable wise person. When they order you to pick up after yourselves in the cafeteria, they can undermine your own freely-occurring sense of courtesy. Imagine a room full of screaming people: truly, it is much easier if they quiet themselves than it is to forcibly quiet them. The way that today’s schools insist on the latter inhibits people from developing the ability to be quiet and attentive on their own.

Let us reconsider safety. Safety is always a dominating concern for everyone hanging out with young people. But the way to promote safety is to help kids to become stronger and more responsible, not weaker and more dependent. Whether you are a parent or not, consider that responsibility encourages strength, while surveillance and control can foster weakness.

Let us not discriminate against the uncertified. If we must assess competence for a given task, let us assess it as directly as we can, and not conflate competence with the length of time spent sitting in educational institutions. Those of us who have spent a lot of time in those institutions can do our part to deflate the value of educational currency by refusing to boast of our own “official” educational credentials. Strike these from your self-image; demand that others judge you by your actual talents and accomplishments, the way you would judge others.

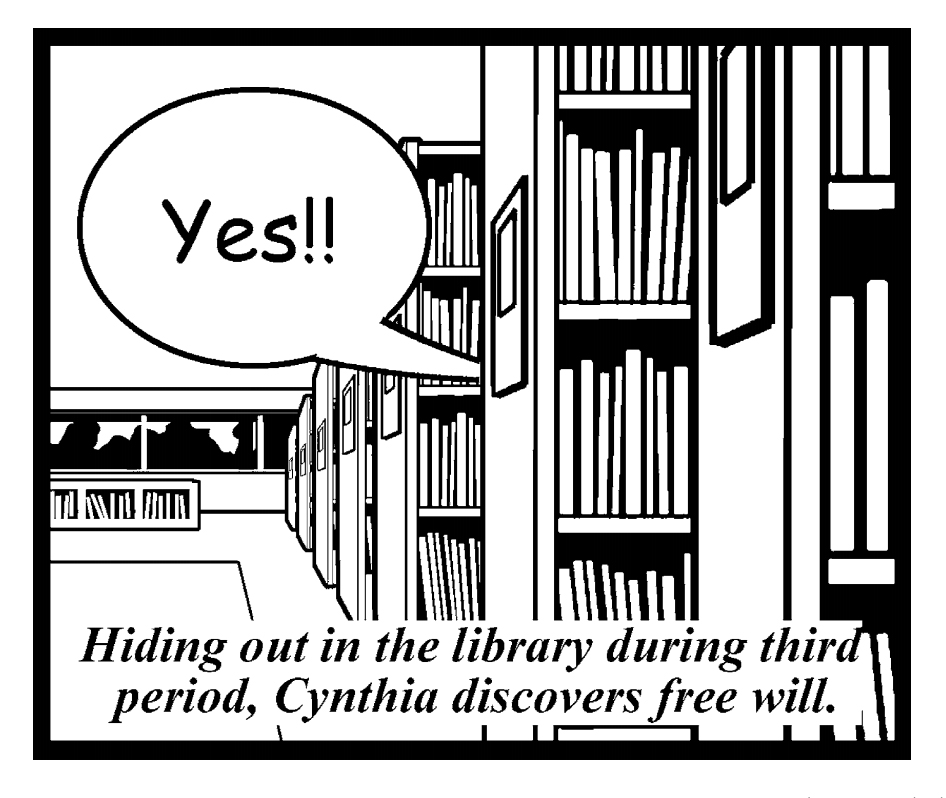

Let us frequent libraries, cooperatives, museums, theaters, and other voluntary, less coercive community institutions. Where they are inaccessible, let us work to make them accessible. Let us create more spaces in our communities where the young, the old, and those in between can get together to pursue un-programmed activities of all sorts. Let us end the policy of shunting young and old into separate institutions “for their own good.”

Let us spit on exploitative labor of all kinds, not just child labor. For the first several hundred thousand years of human existence, young people meaningfully participated in many aspects of securing the collective survival of their communities. It is age discrimination that mandates that young people must be taught about the world before they are allowed to learn from it by participating in it.

Let us learn to think again—and make spaces that encourage it! Book culture depended upon stable social circles and spaces in which we could come together regularly, such as coffee shops and periodicals for writers and readers. Today, both books and dialogue itself are opposed by competing media. The screen dissolves the text. The picture and its caption triumph. Silent and sustained attention is constantly interrupted by programmed noises. Specialized school subjects and the school bells dividing them into regular fifty-minute intervals interrupt the thoughts of any individual attempting to think critically inside the school. Our ability to maintain a sustained thought is under attack from movies and social media, from the noise, speed, and information density of our time. Institutions that aim to prepare students for the insane world that exists—these can only smother the ability to think and feel freely.

Trusting Relationships with Each Another and the Young

We all have observed ongoing conservative culture wars over “family values.” These “values,” of course, are about kids: precious, obedient, little spittin’ images of upstanding agreeable citizens. People wary of change often fear that the young, the heart of the nuclear family, represent a potentially disruptive force.

This suspicion is well-founded. Young people—as anyone who takes them seriously can attest—often demonstrate an ability to draw attention to the political dimensions underlying everyday life: to the dubious pretenses by which authorities, often including parental authorities, establish themselves. Without censure, with the room to be confidently inquisitive and direct, young ones can discern the fundamentals of social relations by unearthing the root—that is, radical—details that betray the reality of those relations, reminding us of the hidden roots of power on which authority rests. Spying that loose edge, they may just pry it back to ask: Why? Why do my sneakers say “Made in Pakistan”? Why are the sidewalks in this part of town crumbling? Why are we supposed to go to school?

Check your motives as you interact with those that you assume you know more than. The educator sometimes undertakes the education of the child with such zeal because jealousy of the child’s clarity spurs him on to try to make this other person more like himself. Likewise, he may be spurred on by resentment of the bravery that aids children in calling out incongruence and injustice.

Because children are all too often not seen as individuals but as objects, as tofu for soaking up whatever marinade they are placed in, they have been used by people with all sorts of motives as testing grounds for a myriad of half-baked solutions to social problems. “Proper child rearing” techniques have been presented as the means to end poverty, crime, urban violence, and general disorder, among other scourges. The child is taught proper social values, attitudes, and work habits to this end; but if she forgets or refuses her teaching, she is shown that as an individual, she is the problem, not the social system responsible for both her lessons and the social problems against which she is supposedly being inoculated.

If we agree that children are good at learning, let our attitude and dealings with young people bear that out. Let us resist the temptation to become educators, to rub the noses of the young in our greater experience by unthinkingly adopting the roles of teacher, helper, instructor. Let us trust people to figure things out for themselves unless they ask for our help. As it turns out, they will ask frequently. People whose curiosity has not been deadened by education are bubbling with questions. The toxicity inherent in education is precisely that so much of the teaching that goes on is unwelcome.

Furthermore, in support of not only young people but all people, we would do well to nurture more accessible everyday places where knowledge and tools are not locked up in institutions or hoarded as closely guarded secrets. It’s easy enough to offer, without imposition, to share our skills with others. Take on an apprentice. Hang a shingle outside your home describing what you do. Let your friends and neighbors know that you can make such an offer to any serious and committed person.

Living Cannot Be Institutionalized

When we enter an institution, whether we do so willingly or by force, we often believe we can extract the good things it has to offer and leave the bad ones behind. However, as one Lakota man famously said about schooling,

“The schools leave a scar. We enter them confused and bewildered and we leave them the same way. When we enter the school we at least know that we are Indians. We come out half red and half white, not knowing what we are.’’

Compromise with institutional influence is usually a fool’s bargain.

If you do not wish to institutionalize your mind and heart within the limitations of school, consider also questioning classic love relationships, transportation norms, and other things people take for granted. Accompany your second look at schools with a second look at all things, all the time. Let us not cede the responsibilities we have to one another to institutions. More and more of us consider it reasonable and virtuous to evade being diagnosed, cured, educated, socialized, informed, entertained, housed, married, counseled, certified, publicized, and protected according to the needs instilled in us by our professional guardians. More and more people are finding that the freedom to resist integration into many of our modern systems is sacred to them.

For Dropouts with Financial Access to So-called Higher Education

Though many of us who are hooked on public institutions find ourselves needing to escape entirely from their grasp, you might find you have the inspiration or delusion it takes to live creatively within the belly of the beast. Truly, we all find ourselves living in some chamber of that belly some of the time, regardless of our life decisions. If you are a young person whose parents have enough resources, and they expect you to go to college on their dollar and earn the credentials to open doors locked to less privileged people, think of clever ways to apply this privilege. Obtain the conventional training to become an MD so as to do transitioning surgeries or electrolysis for low-income transgendered people. Go to law school so you can represent people in court who have refused institutionalization and have been charged with crimes for it. Many a marginalized subculture would benefit from free or inexpensive access to the institutional educational training of someone who can do some of the tricky things that are strictly regulated in this society—helping fit someone for a prosthetic limb, for example.

But should you be interested in receiving such an education, beware. Like Frodo and the ring, to put an institutional tool in your hand temporarily, even if with the goal in mind of destroying its power, is to risk falling victim to its allure and misguiding principles.

Consider other ways to use your access to higher education. Maybe you could take the money you would spend on schooling and channel it to another person for whom college is otherwise utterly inaccessible, who does not wish to—or cannot as easily—interact with the world without proving credentials. On the off chance that your parents support your analysis or respect your divergent viewpoints, ask if their money could be used to fund a brilliant project you have in mind.

Learning Not to Learn, Not Learning to Learn

To think seriously about deschooling our entire lives, we can develop the habit of setting a question mark beside all discourse regarding people’s “educational needs” and supposed need for a “preparation for life,” reflecting instead on the historical context of these ideas. Let us question not only the notion that schooling is a desirable means, but also that education is a desirable end. The alternative to schooling is not some other type of educational agency, nor the integration of educational opportunities into every aspect of life, but ways of living that foster a different attitude toward tools.

Educational function is already emigrating from schools into other sites (on-the-job training, anyone?), and, increasingly, other forms of compulsory learning are being instituted in modern society. Of course, learning itself is not made compulsory by law. Instead, as is typical in consumer society, it is subtly enforced by other tricks, such as making people believe that they are learning something from television programs, or compelling people to attend employee trainings, or getting people to pay huge amounts of money in order to be taught how to have better sex, how to be more sensitive, how to know more about the vitamins they need, how to play games, how to breastfeed, and so on.

What could our lives be if we were to act as fresh waking people every day? Step out of bed to live every moment according to our own self-determination? Eating as we’re hungry, learning how to track down answers, not fearing intimidation from superiors, holding no contempt for the younger, experiencing no anxiety or feelings of inferiority around the older, suffering rarely from boredom, rarely looking to others for approval or critique, nourishing our capabilities to concentrate and carry sustained thoughts?

The talk of “lifelong learning” and “learning needs” has thoroughly polluted not only schools but our whole lives. Potent living consists, as it always did, in a patient and steadfast search for truth, and in the unfolding of capacities that are good and beautiful in themselves, rather than simply because they can secure us financial gain. It takes place in a thoughtful shaping of our surroundings, in conversation, in hospitality. Whoever loves such living will not sacrifice the present to an endlessly postponed future.