Zine : read

Lien original : par Luce deLire via year of the women*

En français : Titre accrocheur : Abolitionnisme de genre, matérialisme trans, et plus encore

In this text, I want to float a hypothesis. I’m not sure it tracks. But I’d hope that it can serve as a touchpoint within a developing debate. My suggestion is that current queer debates in the West (meaning: inside queer scenes) can be mapped on a spectrum between two poles: Gender abolitionism and trans materialism. These poles are neither solid positions nor official parties. It is possible that nobody actually subscribes to any of them fully. Yet I do find it useful to articulate both poles so as to shed light on certain discursive tendencies. I will argue that both poles have their own particular relations to capitalism: gender abolitionism understands gender as property, while trans materialism understands gender as commodity. A way to move beyond the two, or so I shall suggest, is the following: find anti-capitalistic counter-paradigms to private property as primary kind of social relation, de-commodify gender, unlearn violence.

To start, it seems as though gender was discussed between two aspects: An interior emotional aspect and an external social aspect. The former is felt, the latter is ascribed. The former is accessible only to a certain individual, the latter is accessible to a collective agent such as a culturally specified group. The core disagreement, as I see it, is about which of these two aspects – external / internal – takes precedent in the determination of one’s identity. Gender abolitionists emphasize internal self-determination while everything else is understood to run a high risk of organizing society in a violent and oppressive way.[2] Trans materialists understand gender (and identity more generally) as an aspect of social intelligibility, a way in which people recognize each other, while the introspective, emotional counterpart is a response to such social embeddedness. The crucial question is thus: Is social intelligibility a real aspect of gender or is social intelligibility merely an external imposition onto an internal core of identity?[3]

I. Gender Abolitionism

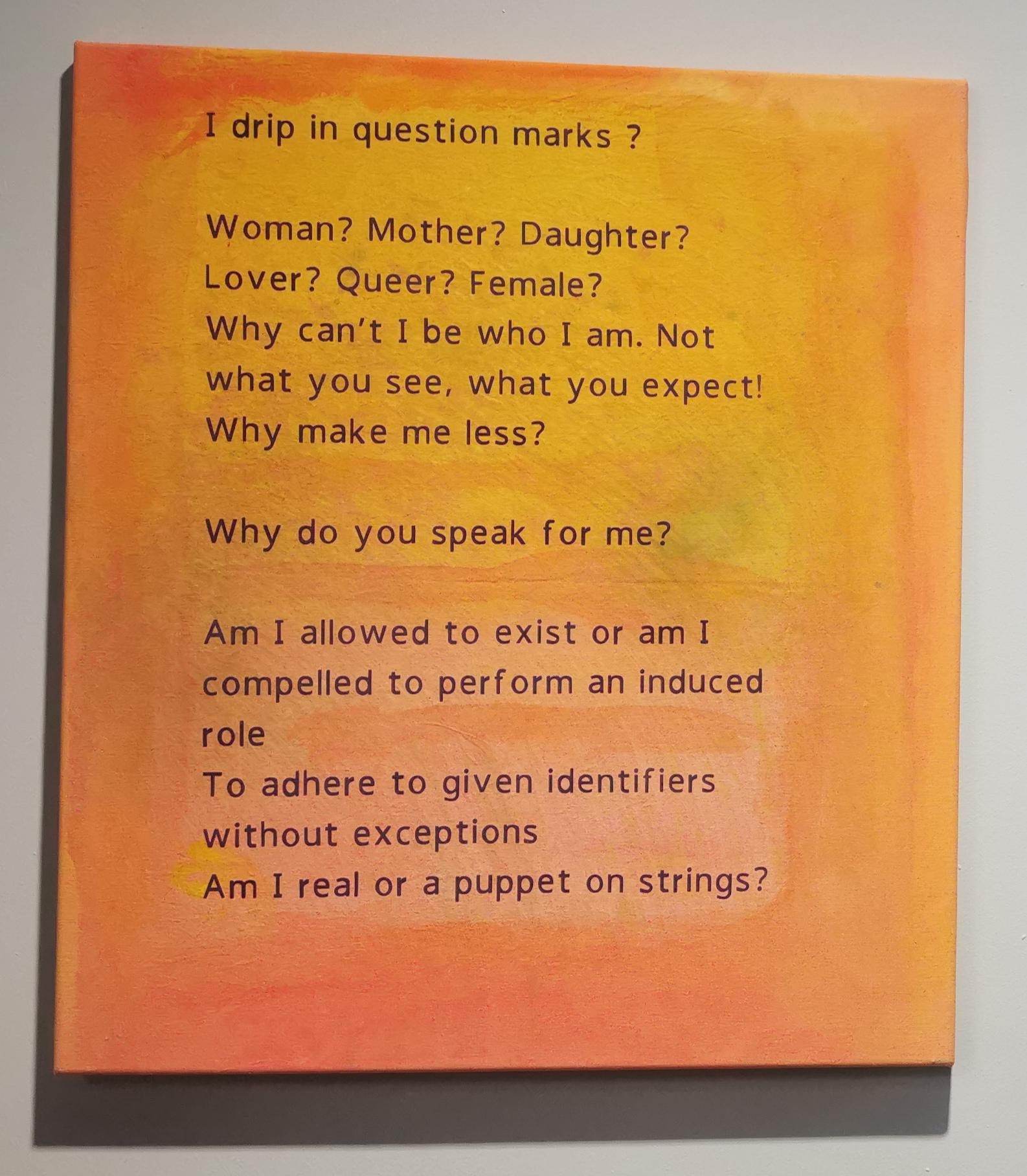

A nice example for gender abolitionism is Amora C. Bosco’s Runes of my being emboldened (2022), exhibited at Documenta 15 in Kassel. The work is a series of poems printed on silkscreen, one of whom is titled I drip in question marks? Let us focus on its first verse:

“Woman? Mother? Daughter?

Lover? Queer? Female?

Why can’t I be who I am. Not

what you see, what you expect!

Why make me less?”

These questions are clearly rhetorical. The speaker insists on being who they are as opposed to an external infringement, from captivation by labels and social functions. The I beyond expectation, beyond what is being perceived is said to be more than the one mediated through labels and social functions. The poem articulates an aspiration to replace the socially intelligible aspect of gender with another “real” way of existence. This “real” way allows the speaker to “be who I am” and is juxtaposed with an apparently unreal “puppet” that is controlled externally through strings. Metaphors of external interference abound: “what you expect”, “make me”, “speak for me”, “compelled”, “induced”, “adhere to” etc. Inversely, the envisioned kind of existence would thus be beyond such external interferences – beyond strings, beyond expectations etc.

Taking this poem as our paradigmatic case, gender abolitionists essentially envision leaving it up to each individual to count as this or that, notwithstanding a collective process, traditional understandings, material conditions or legal sanctioning. What is a “Woman? Mother? Daughter? Lover? Queer? Female? Why can’t I be who I am.” There is no question mark here. Obviously, the speaker already is what they are. There is thus no point in making them not be what they anyway are. Yet they cannot be that person. Even more radically, we might read “Why can’t I be who I am. Not” to mean: why not become someone that does not exist (yet)? Why curb the potential? The underlying message is: Nobody should interfere with what a person is from the outside because there is no way to change someone’s essential way to exist. “Why make me less” while the “real” way “to exist” is just the way one already is (which may or may not be fluid)? There are only two options here: violent coercion and liberated self-expression. In the words of Marquis Bey: “[N]ormativity” is “necessarily violence”, while “subjectivity” is “the ability to be other than what we are.” The latter is presented as the good way to exist. It is a desire for self-expression as non-interference. Implicitly, then, the poem suggests that everybody ought to desire absence of external interference into one’s own business for oneself and for others – for we should desire the good, should we not? Consequentially, everything else may be read as crossing boundaries or violent manipulation.

The poem falls within what I have called the Esoteric Matrix, a form of queerness highly compatible with neoliberal capitalism.[4] The common denominator between gender abolitionism and neoliberal capitalism is negative freedom.[5] Negative freedom is the absence of external interference. Freedom from taxes, discipline and physical obstacles are kinds of negative freedom. Now, ideologically speaking, property is exactly negative freedom manifested in an object. For nobody has the right to interfere with my use of my property – that’s what makes it mine. Thus, my shoes are mine in that I can determine how to use them, who uses them etc. Under neoliberal capitalism, negative freedom (absence of external interference) is the highest virtue. It is the freedom to own and the freedom to use what is owned, hence the freedom to consume. Beyond the poem, gender abolitionism holds that identity can only be determined through individual introspection, while gender is necessarily an external determination. Expressions of identity should not be interfered with in any way, which is why gender is inherently suspicious. The emphasis on introspection in the determination of identity dovetails well with the neoliberal universalization of the property form: what’s mine is mine and ought not to be subject to anyone else’s judgment, interference or control. Furthermore, where negative freedom is the ultimate virtue, social inclusion is the political aspiration.[6] For arguably, the sphere of non-interference aka a neo-bourgeois society in its ideal form would technically provide a maximum of negative freedom.[7] Consequentially (and beyond the poem), access to all kinds of existing social institutions is a primary demand of queer activism of this kind. The reason is that non-access is understood as interference with the freedom to self express. Examples are queer families, queer police officers, queer conservatives etc.

II. Trans Materialism

We find an example for trans materialism in Fadi Aljabour’s Breathing Inside Your Guts III (2021), also exhibited at Documenta 15 in Kassel. A large hole on one side, the inside of which disappears in darkness, the sculpture is covered in fur of different shades of blue. In many visitors, the work inspires the desire to touch the fur. The curators even ordered a guard to sit in proximity to the work so as to advise people not to touch the work. The work, then, is an intervention into libidinal space, drawing people towards it while simultaneously insisting on the prohibition of the desired action (to touch the work). Simultaneously, visitors often try to look into the darkness encapsulated by the furry object, seeking to get a peek onto the hidden inside. Yet in order to succeed with that you would have to lean into the cavity or reach into it and break the integrity of the work yet again. Breathing Inside Your Guts III thus literally produces the desire to break into the work, to cross a boundary. The Guts in the title are the work itself. The work does not represent an identity. Rather, it causes an effect, namely the desire to get intimate (to touch). Breathing Inside Your Guts III is a political intervention, heterogenous to queer politics as it is currently conducted. It works with libidinal landscapes in conversation with material resistances, desires that really occur in the space.

Along these lines, some float the trans materialist hypothesis.[8] The hypothesis goes as follows: Gender is first and foremost intelligibility to the desire of an other. “What makes gender gender —the substance of gender, as it were—is the fact that it expresses, in every case, the desires of another.”[9] In other words: Gender is a way in which we are known to each other’s wanting, interest, lust, etc., (understood not necessarily in a sexual way, although sexuality plays a particular role here). Gender is libidinal intelligibility. This includes intelligibility to our own desire as someone else, perceiving ourselves through the others, through a mirror, through writing and re-writing ourselves. We may or may not like how others refer to us, treat us, integrate us in their social interactions. In that assessment, we conceive of ourselves through others. Likewise, looking into a mirror inspires self-reflection as an other, as a desiring subject (there is a longer story to be told here but I will suspend it for now). Gender is a hinge that regulates whether we will friend zone one another or make a move or check each other out or trust or seek protection etc. It’s hyper-stratified, meaning that ‘male/female’ are by no means the only designations relevant in its sphere. Rather, gender has many shapes and forms, from butch to daddy, from migrantifa boy to bourgeois enby through ace to doll and back. Combinations and creative aberrations abound. Desire in the form of sexual orientation constantly blurs into gender. Desire functions as the message in a subtle system of omissions and allusions called ‘gender’. That subtle system is a dance. It’s poetry. It’s plastic, multidimensional. It incorporates other aspects of social intelligibility, such as race, class, ability etc. In fact, the distinctions between race, class, gender and other categories are artificial devices, made to communicate our grievances to the law, the master, the authorities.[10] Yet we are friends, lovers, adversaries and nemeses to each other, not judges and authorities. Intersectionality is not enough.[11] To the trans materialist, gender is the navigation system that points us towards an interest for each other, a desire to be close to one another or – inversely – to stay away from one another etc. If so, there is no expression of gender. Gender itself is that expression. If you think it should not be called ‘gender’ – I agree. It’s libidinal intelligibility as an aspect of social intelligibility. Yet I will stick to the traditional term ‘gender’ in order to preserve readability and textual flow.

Gender abolitionism ties into neoliberal capitalism by understanding identity as a kind of property. Trans materialism ties into neoliberal capitalism by understanding the gendered body as a commodity. To see this, consider that the most encompassing structure of gendered violence is currently the commodification of desire.[12] Bini Adamczack says it as follows:

« The love market [or: the market of desire] […] is premised on competition […]. There are enough lovers for everyone, but not everyone gets one – or ten. […] The wealth of the sexual economy presents itself as an immense accumulation of the most various bodies, all of which are desireable – and exchangeable. However, supply is restricted […], the exchange is blocked from the start. »[13]

Scarcity of desirability regulates access to friendship, love, sex, care and other manifestations of desire.[14] Gender, race, class and other categories are aspects of this general and in itself artificial restriction of desirability. These restrictions give birth to desirability as a commodity. Here, value is determined in relation to other more or less desirable bodies, but most of all in their likeness to a given paradigm, such as the cishet white able bodied sporty type etc. This is how trans materialism ties into neoliberal capitalism: It insists on the reality of the commodified market of desire and understands the gendered body as a commodity, determined by its intelligibility to the desire of an other. There is thus no way not to be gendered. “[I]f there is any lesson of gender transition—from transition—from the simplest request regarding pronouns to the most invasive surgeries—it’s that gender is something other people [mostly cis people] have to give you. Gender exists […] in the structural generosity of [mostly cis] strangers.”[15] That is why for trans materialists, the way forward is productive intervention and appropriation instead of proper self-determination and accompanying representation.

III. Troubling Representations

Most people are not full-on gender abolitionists. Many, however, do exist on the gender abolitionist spectrum. The problem for proponents of these softer gender abolitionisms is not libidinal representation itself but the constant misrepresentation of someone’s identity. Positions such as Bosco’s in the poem above seem to be driven by a desire to eradicate such misrepresentation. Asking people for their pronouns, suspending one’s assumptions on someone’s gender or sexual identity and declaring gender to be the subject of introspection and self-determination exclusively are practices that often manifest this desire – the desire not to misrepresent.[16]

But is it possible not to misrepresent? For it seems that representation comes with the possibility to mis-represent. Jacques Derrida calls it a necessary possibility – a possibility that is always given. Whence that possibility? There are many reasons for the necessary possibility to misrepresent. Here is one:

The message most likely to arrive is the one that has been there all along. For intelligibility itself is based on repetition. You see what you know. Things appear to you in relation to things you have seen before. Any understanding requires some kind of framework. The same counts for representation. Likewise, every act relies on something that has existed previously. Everything is created from whatever is at hand. No expression without repetition. Repetition is the only way forward. Consequentially, we repeat. Constantly. Yet these repetitions occur in changing situations and combinations, alternative contexts. That is why each repetition looks different. Repetition is always repetition with a difference, where the exact nature of that difference is strictly indeterminate. Correct representation is representation according to some model or intention that we posit. Yet the correct application of any model relies on its repetition with a difference (as just pointed out). And some of these differences will inevitably track as ‘wrong’, according to context. The reason is that the sphere of correct representations is strictly determinate (my pronouns are she/her and nothing else, etc.), while the sphere of misrepresentations is strictly indeterminate (it may occur implicitly, emotionally, accidentally and differently in each and every context). Misrepresentations cannot be tamed. They will always occur. They are sources of creative intervention just as they are sources of painful misgendering.[17]

Misrepresentation thus cannot be avoided in principle. The question cannot therefore be Misrepresentation yes or no? In fact I want to suggest that misrepresentation was never the problem to begin with. The problem is and has always been violence. The problems addressed by queer activism are lack of hospitality and empathy for the life of the other. They manifest as entitlement, unwillingness to unlearn, lack of sensitivity, insistence on one’s own privilege etc. The relevant question is thus not how to avoid misrepresentation. The relevant question is: How do we unlearn violence?[18] Gender abolitionists respond: By representing appropriately. Trans materialists respond: By intervening appropriately.

While for gender abolitionists, ‘gender’ is inherently oppressive by virtue of its external designation, to trans materialists, gender is merely the intelligibility to the desire of an other and thus not inherently oppressive. If someone reads my gender, they recognize their own desire in me. They may think I’m repulsive or a promising mother to their child or hot. They may project that I want to get married, to make a career, to suck dick etc. I, in turn, may want to befriend or stay away from them, etc. In any case: Gender is first about someone else’s desire (and about my own desire as an other to myself). However, I may feel good about being desired in this way, or by these people etc. Yet again: There is no expression of gender. Gender itself is that expression. And the question, for a trans materialist, is not: Am I being read correctly? The question is: Do I like how I am being read? In other words: From an abolitionistic perspective, the relevant political question is epistemological, while from a trans materialistic perspective, it is affective in nature.[19| It remains to be spelled out what a good society would look like in either model. What does a society of pure self-determination look like? What does a society of good gender relations look like? Which social institutions are required in order to enable proper self determination on the one hand, mutually enhancing desires on the other hand? What are the end games here (if there are any) – and are they necessarily opposed, different or mutually exclusive? These questions must remain unanswered for the moment. But I do hope that I can return to them in due time.

IV. Capitalism and Beyond

The essential difference between gender abolitionism and trans materialism is the difference between gender as property and gender as commodity, between gender as a private affair and gender as a collective process, between gender as an object of non-interference and gender as an object of a libidinal economy. Returning to Bosco and Aljabour, we can see this prominently: While Bosco’s painting/poem insists on the absence of external interference into gender as an individual affair, Aljabour’s sculpture intervenes in the collective negotiation of desirability by way of appealing to given patterns of desirability (fur, darkness, the prohibition to touch a work of art) while it is using the institutional setting that it occurs in (Documenta 15 as an institution that will provide policing to make sure the work is not touched). Bosco’s work emphasizes the property aspect of gender, while Aljabour’s work manifests the oscillation between property (the untouchable work) and commodity (the collective desire to touch).

Both, trans materialism and gender abolitionism, however, accept different aspects of capitalism as a given – and necessarily so. For in Western societies, capitalism is still the principle determining factor of social interaction. Yet they also re-enforce these aspects. For tragically, any intervention that is not anti-capitalistic will inevitably bear the mark of complicity.[20] Yet the problem is not some individual person’s behavior or belief system. The problem is that the logic of capitalism permeates (and constitutes) identities and the discourse about them. This is where I strongly disagree with Kadji Amin’s analysis in We Are All Nonbinary. Amin analyzes (some branches of) non-binary discourse roughly along the lines of what in this text I call gender abolitionism and then states that “problems with non-binary identity and discourse are not the fault of nonbinary people alone.“[21] Yet in fact, problems with gender abolitionism (or, in the case discussed by Amin, non-binary discourse) are not the fault of gender abolitionists at all. These problems are symptoms of neoliberal capitalism and the commodification of individuality, identity, personality or however you’d like to call it. The enemy is not the gender abolitionist per se. The enemy is and remains capitalism and the various kinds of complicity that capitalism solicits, never mind who embodies them.

Given that under neoliberal capitalism, gender is commodified as described above, it is an artistic task, a political task, a task for writers, activists, politicians, administrators, friends, lovers, performers, painters, architects etc. to come up with concrete ways to undo, to unlearn commodified desire.[22] In other words: Which existing counter-paradigms can we use to re-engineer gender beyond the logic of private property and the commodity form? And more generally: Where are we intelligible to one another in ways that are not primarily mediated by capitalism?[23] What do desire, friendship, rage or even hate look like beyond the confines of surplus value (commodification) and the social distance engendered by the exclusionary logic of individual ownership (private property)? These counter-paradigms are the reservoirs of life beyond capitalism and thus life beyond commodified gender (be it as private property or as commodity). In this text, I have tried to present to you some pieces of the puzzle as I see them, some framing maybe to guide someone’s journey through archives of artistic interventions and queer politics, looking for more pieces of this or other puzzles: the juxtaposition of gender abolitionism and trans materialism, their particular relations to capitalism as emphasizing the property aspect (gender abolitionism) and the commodity aspect (trans materialism) of libidinal intelligibility. And finally a way to move on: find anti-capitalistic counter-paradigms to private property as primary kind of social relation, de-commodify gender, unlearn violence. Initially I ended this text on: “A proper final statement is above my pay rate.” I was told during the editing process that leaving this as a last sentence was not as funny as I might think it is. I don’t actually think it’s funny. I’m being paid 200 Euros for this text – roughly 5000 words and many hours of work, editing and conversation. In an age of increased queer and trans visibility, it is worth pointing out that this text is a product of exploited labour. I did know this when I agreed to write it (within the given constraints). I have my own song to sing regarding underpaid intellectual labour and its political consequences. And yet: A proper final statement is above my pay rate.

With many thanks to: Li Alt, Alaida Hobbing, Vera Hofmann, Aaina Lakha, Sebastian Moske, Nina Tolksdorf, McKenzie Wark, Mine Pleasure Bouvar Wenzel and my mother.

September 2022

_________

[1] I had initially planned to write about the title the Schwules Museum Berlin (gay museum Berlin) assigned to its curatorial program in 2018: “Year of the Women*”. The title of my own piece – “Catchy Title” – stands as a remainder of that original project. My idea was that different interpretations of that title could be mapped onto the conceptual spectrum discussed in this text. The original version of this essay then ended with roughly two pages of questions regarding the curatorial project, institutional critique in general and the institutional, emotional and political difficulties of intervening into certain queer debates. Yet during the editing process, it has become clear to me that I would rather not extend myself into the emotional landscapes I am faced with here. I do, however, thank the Schwules Museum for their collaboration and for the opportunity to contribute from the sidelines. I hope that what I have to offer will resonate with the context in question regardless.

[2] That’s how I read for example Marquis Bey, Black Trans Feminism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022)

[3] This is related to the core disagreement articulated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak over against Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze in Gayatri C. Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory – A Reader, ed. Patrick Williams, Laura Chrisman (New York: Columbia University Press: 1994) 66-111. I transpose the debate onto contemporary queer discourse in Luce deLire, “Can the Transsexual Speak?,” in Subjects that Matter, philoSOPHIA, Special Issue 10/2022, ed. Namita Goswami (New York: Suny Press, 2022, forthcoming)

[4] Luce deLire, “The New Queer,” Public Seminar, August 19, 2019, https://publicseminar.org/essays/the-new-queer/

[5] For a related point, see Kadji Amin, “We Are All Nonbinary: A Brief History of Accidents”, in: Representations (2022) 158 (1): 106–119, 115

[6] See also Luce deLire, Can The Transsexual Speak? (forthcoming)

[7] See for example Carlos Ball, The Morality of Gay Rights: An Exploration in Political Philosophy (London: Routledge 2003), pp. 17, John Rawls, Political Liberalism (New York City: Columbia University Press 2005), Carole Pateman, The Sexual Contract (Cambridge: Polity Press 1988), Charles Mills, Black Rights White Wrongs (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2017), Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia (Basic Books, Inc., New York 1974)

[8] I call this “trans materialism” because it grows out of the experience of gender transitioning in particular. For example here: “[I]f there is any lesson of gender transition—from transition—from the simplest request regarding pronouns to the most invasive surgeries—it’s that gender is something other people [mostly cis people] have to give you. Gender exists […] in the structural generosity of [mostly cis] strangers.”Andrea Long Chu, Females (New York City: Verso 2019) (e-book, n.p.) See also: Luce deLire, Can the Transsexual Speak? (forthcoming) and Comrade Josephine, Luce deLire, “Full Queerocracy Now!: Pink Totaliterianism and the Industrialization of Libidinal Agriculture”, in: McKenzie Wark (ed.), E-flux Journal #117 April 2021, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/117/386679/full-queerocracy-now-pink-totaliterianism-and-the-industrialization-of-libidinal-agriculture/

[9] Andrea Long Chu, Females (New York City: Verso 2019). Chu understands this ‘desire of another’ as a somewhat forceful imposition. I disagree with her on that. Amin argues along similar lines (Amin 2022, 115).

[10] For more on this, see: Luce deLire, “The Death of Critique and its Rebirth in Traumatic Attachment.” in: Göksu Kurnak and Andrea Bellini (ed.), The Artist Starter Kit, Centre d’Art Contemporaine Genève 2023 (forthcoming)

[11] For more on this, see Luce deLire, “Can the Transsexual Speak?” (2022, forthcoming) and Luce deLire, “The Death of Critique and its Rebirth in Traumatic Attachment,” in The Artist Starter Kit, ed. Göksu Kurnak and Andrea Bellini (Geneva: Centre d’Art Contemporaine Genève, forthcoming)

[12] Tiqqun, Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl, trans. Ariana Reines (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2012), Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie, trans. Bruce Benderson (New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2013)

[13] Bini Adamczack, “A Theory of Polysexual Economy (Grundrisse)”, in: Eleanor Weber, Camilla Wills, What The Fire Sees (Brussels: Divided Publishing, 2020), pp. 164

[14] For an overview of positions on the various connections between desire and economy, see Jule Govrin, Begehren und Ökonomie (Berlin: De Gruyter 2020)

[15] Andrea Long Chu, Females (New York City: Verso 2019) (e-book, n.p.)

[16] A note on the term “gender abolitionism”: Alaida Hobbing pointed out to me that there is a conceptual gap between full gender abolitionism and soft gender abolitionism. For in a full on gender abolitionist perspective, gender as an oppressive system cannot be represented properly because it always works as a violent imposition. Yet a soft gender abolitionism may allow for some real gender to be determined by introspection. This is indeed a problem because it may appear as though gender abolitionism was a misnomer to begin with. Along these lines, Mine Pleasure Bouvar Wenzel suggested to me that gender abolitionism may more productively be understood as the project to abolish gender as an (oppressive) system that orders social and material conditions (Ordnungskategorie). This abolition may then be understood to be a necessary step in the abolition of capitalism. I take both points to be valid. However, the common denominator between soft and full gender abolitionism that I am interested in here is exactly the emphasis on the internal process as opposed to an external imposition. That is why I say that soft gender abolitionists reside on the gender abolitionism spectrum, although they may not themselves want to abolish gender altogether. Similarly, there may be a space for a Wenzelian radical gender abolitionism as an anti-capitalistic project with stronger ties to the trans materialistic model. I would like to see that project spelled out. Yet for the moment, I will only mark it here and leave it in a footnote, possibly for someone else to pick up on.

[17] For more on this, see Jacques Derrida, “Signature Event Context,” in Limited Inc., trans. Samuel Weber and Jeffrey Mehlman (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1972) and Gayatri C. Spivak, “Review: Revolutions That as Yet Have No Model: Derrida’s Limited Inc,” by Jacques Derrida. Diacritics 10, no. 4 (1980): 29–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/464864., also Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri C. Spivak (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press 1974)

[18] See also Luce deLire, “Why Dance in the Face of War?,” in Stillpoint Magazine 010: JUDGE (2022) https://stillpointmag.org/articles/why-dance-in-the-face-of- war/

[19] To the trans materialist, gender is the intelligibility to the desire of the other. I identify as gay, ace etc. because my desire is reflected back to me in particular ways. I want to do this or that, befriend these or those people, react more or less well to being approached in this or that way. Etc. That also means: desire is never purely given (as mine). It shows up only insofar as it is mediated through something else. Desire itself is thus the fantasmatic truth of our social position regarding where/how/when we want what. However, whatever we can discern is only intelligibility (that’s what intelligibility is – discernability, perceivability etc.). Epistemologically speaking, there is only gender. Desire, then, is articulated regarding gender. But it does not exist outside of its articulation. Desire is a necessary reference point of such intelligibility, yet it is in itself indetermined. It exists only in its intelligible manifestations, as gender. And yet gender qua libidinal intelligibility must refer to something that is not itself. The distinction between the two is what I call an intimate distinction: both are one and the same thing in different respects (for someone on the one hand, in itself on the other hand; intelligibility on the one hand, reality on the other hand – with the twist that intelligibility is itself a dimension of reality and reality cannot exist other than through intelligibility).

[20] See also Luce deLire, “L’Ancien Régime Strikes Back: Letter to Paul B. Preciado,” e-flux, January 2018 https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/l-ancien-regime-strikes-back-letter-to-paul-b-preciado/7566

[21] Amin 2022, 117

[22] I have tried my hands on this in Luce deLire, “Lessons in Love I: On Revolutionary Flirting”, in Stillpoint Magazine 009: TENDER (2021) https://stillpointmag.org/articles/lessons-in-love-i-on- revolutionary-flirting/; Luce deLire, “Why Dance in the Face of War?” (2022); Luce deLire, “’The neighbor as a metaphysical constant of virtuality’ – Permeable Subjects: A column”, co-authored and ed. Lene Vollhardt, April 1, 2020, http://artsoftheworkingclass.org/text/metaphysical-neighbors and Luce deLire, “Unlearning Property, Unlearning Violence: The Queer Art of Hospitality“, in Lo: Tech: Pop: Cult: Screendance Remixed, ed. Priscilla Guy and Alanna Thain (London and New York: Routledge 2023)

[23] This point is painfully missing from Amin’s We Are All Nonbinary, especially in its final sentences: “[W]e must, first and foremost, relinquish the fantasy that gender is a means of self-knowledge, self-expression, and authenticity rather than a shared, and therefore imperfect, social schema. This means developing a robust trans politics and discourse without gender identity.” (Amin 2022, 117-118)